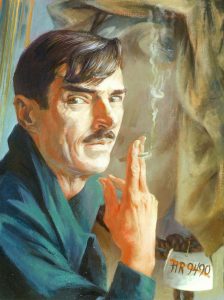

Victor Arnautoff, Self Portrait, 1934

The artist included this self portrait in his “City Life” mural.

Photo Credit: Robert Cherny

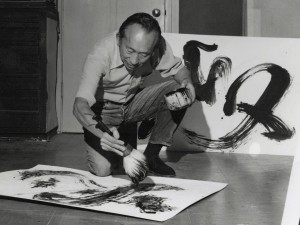

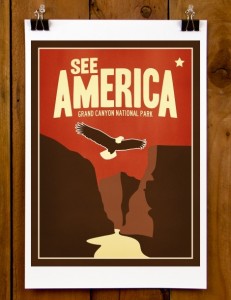

Victor Arnautoff was a prolific artist of public murals during the New Deal, many of which are still in place.

Born in Russia in 1896, Arnautoff was a cavalry officer in WWI and later in the White Siberian army during the Russian Civil War. Escaping into northeastern China, he married and his father-in-law paid for him to attend the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. His first public mural, in 1929, can be seen in the city’s Old Cathedral of the Holy Virgin.

Arnautoff and his family moved to Mexico where he worked as an assistant to the famed muralist Diego Rivera. Returning to San Francisco in 1931, Arnautoff gained attention by painting a large fresco mural on his studio wall. He then did several fresco panels at the Palo Alto Clinic that remain on view.

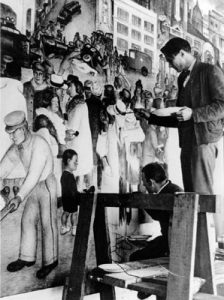

Painting the mural “City Life.”

San Francisco’s Coit Tower, 1934

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the History Center, San Francisco Public Library

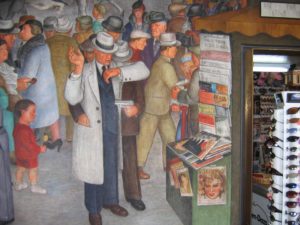

With the New Deal in 1933, federal funds became available for public art. In San Francisco, the Public Works of Art Project hired 25 artists to create murals at Coit Tower. Arnautoff, highly experienced in fresco technique, was designated technical coordinator of the project. His mural, City Life, completed in 1934, presents a vivid kaleidoscope of downtown San Francisco at a time of economic and social upheaval.

Arnautoff’s next New Deal commission, a large mural in the Protestant chapel at the Presidio of San Francisco, funded by the State Emergency Relief Administration, depicts historical vignettes and contemporary activities at the military base, including the Army’s supervision of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Arnautoff at work

George Washington High School, San Francisco, 1936

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the History Center, San Francisco Public Library

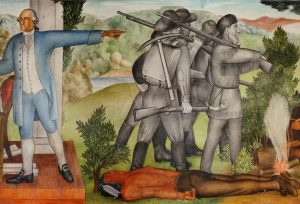

Arnautoff’s political views moved to the left in the mid-1930s, and he sometimes incorporated social criticism into his art. His largest single New Deal commission was thirteen fresco panels on the life of George Washington, painted in 1936 at the newly built George Washington High School in San Francisco. Funded by the WPA’s Federal Art Project, the murals present a counter narrative to the high school history texts of the time: the panel on Mount Vernon emphasizes Washington’s dependence on slave labor, and that on the westward “march of the white race” (Arnautoff’s description) shows it taking place over the body of dead Indian.

He exhibited at the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition, the 1935 California Pacific Exposition, and the 1940 New York World’s Fair.

Mural, “Life of Washington,” George Washington High School, San Francisco

The fresco, consists of 12 panels and measures 1600-square-feet

Photo Credit: Richard Evans

Between 1938 and 1942 Arnautoff completed five Treasury Section post office murals. Those in College Station and Linden, Texas, prominently featured African Americans, rarely depicted in public artworks. His post office murals can still be seen at Linden and at Pacific Grove and South San Francisco, California. Arnautoff’s mural for the Richmond, California, Post Office was recently discovered in a packing crate in the post office’s basement. It is being restored for exhibition in the Richmond Museum of History.

Victor Arnautoff, Self Portrait, c:1950

Arnautoff painted this self-portrait opposing HR 9490, the McCarran Internal Security Act. The Act required Communist organizations to register with the U.S. Attorney General and established the Subversive Activities Control Board.

Photo Credit: With kind permission of INVA publishing house, Russia

In the 1950s, Arnautoff, while teaching at Stanford, was shunned for his leftist views and was interrogated by the House Un-American Activities Committee. In 1963, after the death of his wife, he emigrated to the Soviet Union where he continued to paint and make prints and created three large public murals using mosaic tiles. He died in 1979.