President Roosevelt and his circle believed in the value of the public realm and public service, so they made government investment in public goods such as parks, schools and civic buildings a pillar of the New Deal. Along with its immense building programs, the New Deal brought a level of government support for public art never seen before-–or since. This is reason enough to celebrate the legacy of New Deal art.

The Treasury Section of Fine Arts and the Federal Arts Project of the WPA are the best-known programs, but there were others: The Public Works of Art Project of the Civil Works Administration, the Art and Culture Projects of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, and the Treasury Relief Arts Project. Together they produced tens of thousands of artworks, most of which still adorn public places and brighten the lives of Americans to this day.

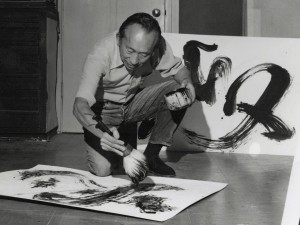

New Deal art programs employed thousands of unemployed artists during the Great Depression, establishing careers and sometimes literally saving lives. Some of America’s greatest artists worked under the New Deal, such as early 20th century giants like Edward Hopper, Thomas Hart Benton and Maynard Dixon. Followers of the famous Mexican artists Diego Rivera and David Siqueiros, like Bernard Zakheim, Victor Arnautoff and George Biddle, produced inspirational murals. Postwar Abstractionists Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Phillip Guston and Lee Krasner came out of the New Deal, as did a host of artists of color such as Sargent Johnson, David Park, Charles Davis, James Auchiah, Gerald Nailor, Jo Mora, Lusi Arenal, Dong Kingman and Isamu Noguchi.

New Deal artists were not just diverse and prolific, they had wide license to exercise their inspiration and talents. As a result, the quality of New Deal art deserves respect for its aesthetic brilliance and originality. A recurrent thread of celebration of American life runs through much of public art of the era, but New Deal artists frequently infused their works with social commentary and criticism. Because people today understandably question art that includes dishonorable people and practices from America’s past, hasty judgement of New Deal murals frequently miss their qualities and subtleties.

Full appreciation of New Deal art can also be impeded by the dominant painting styles of the time, Social Realism and American Scene, which have long been out of fashion. Social Realism has often come under attack for its celebration of manual (and masculine) labor and resemblance to Soviet art, while American Scene painting is dismissed for being nostalgic and vernacular. Only recently has art of the New Deal-era enjoyed a revival in the art world.

New Deal art is all around us yet too often poorly maintained, unmarked or inaccessible to the public. A growing number of these artworks are jeopardized when the buildings that house them are torn down or renovated. Our society needs to value and protect the New Deal’s legacy of public-spirited art. Furthermore, we sorely need a new New Deal to support struggling artists of today so that they may create diverse and inspiring imagery for the future.

The Living New Deal offers recommendations to communities and institutions dealing with challenges to New Deal artworks.