Dorothea Lange, White Angel Breadline, San Francisco, 1933

Collection SFMOMA, Gift of Steven M. Raas and Sandra S. Raas; © Oakland Museum of California, the City of Oakland, gift of Paul S. Taylor; photo: Don Ross.

The process felt like a treasure hunt—or Christmas morning. Box by box, my San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) colleagues and I sifted through 870 artworks made under the Works Progress Administration (WPA), most of which hadn’t had eyes on them for years.

Working throughout 2021 in the museum’s subterranean storage, I and three fellow curators narrowed down our WPA collection to just over fifty objects that would comprise our 2022 exhibition A Living for Us All: Artists and the WPA.

One of the ideas that propels my curatorial practice is my strong belief in the lessons historical material holds for the present. SFMOMA has stewarded an allocation of WPA art works and ephemera since 1943, when the federal art programs concluded and thousands of artworks commissioned during the Great Depression were distributed to institutions across the country.

David P. Chun, Unemployed, ca. 1935

Collection SFMOMA, Albert M. Bender Collection, gift of Albert M. Bender; © Estate of David P. Chun; photo: Don Ross.

Nearly eighty years later, when the precarity that typically clouds many artists’ livelihoods was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the time seemed ripe to look back on the WPA as a model for what’s possible when art is regarded as a public resource. During the Great Depression, the WPA sustained some 10,000 artists whose works have come to define the American experience.

Since this swath of SFMOMA’s collection has been so understudied, our first step was to catalog the range of WPA artworks, which spans paintings, prints, photographs, sculptures and textiles. Piece by piece, we recorded such information as the name of the artist, title, medium and date, while noting objects that impressed us as true standouts—whether for their artistry, subject matter or condition. A particularly thrilling find was a vibrantly colored, abstract tapestry by the artist George Harris so pristine that it’s likely that the box it was stored in hadn’t been opened in decades.

Sibyl Anikeef, Filipino Lettuce Worker, Salinas, California, 1936

Collection SFMOMA, The United States General Services Administration, formerly Federal Works Agency, Works Projects Administration (WPA), allocation to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; photo: Don Ross.

As cataloging progressed and the pile of standouts grew, so did the number of possible themes for the exhibition. The selection coalesced around themes like labor and industry, but also—surprisingly— surrealism and abstraction. I had always associated art of the 1930s and 1940s with social realism, but the amount of work more abstract in nature was truly astonishing.

Gradually, it became clear that the central contribution of our exhibition would be to underscore the WPA’s eclecticism, recuperating the vast scope of styles the artists turned to in giving visual form to their communities and circumstances. It was thrilling to display artworks of different media together in the same space, which is somewhat atypical of collection presentations at SFMOMA.

Sibyl Anikeef, Cypress, 1941

Collection SFMOMA, The United States General Services Administration, formerly Federal Works Agency, Works Projects Administration (WPA), allocation to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; photo: Don Ross.

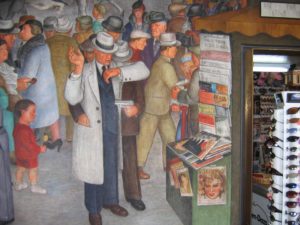

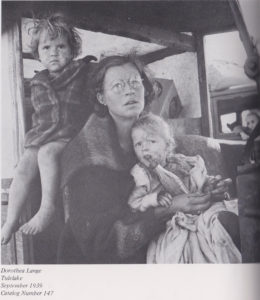

Our strategy to interweave media enabled us to draw unexpected connections. One such highlight was juxtaposing a woodblock by David P. Chun with a documentary photograph by Dorothea Lange, both depicting the White Angel Breadline on San Francisco’s Embarcadero. Lange’s portrait is iconic, so it was remarkable to discover a print depicting the same scene and with a different, wider perspective. Whereas Lange focused on one man to symbolize the struggle of many, Chun exploited the woodcut technique’s capacity for texture to underscore the weariness in his subjects’ faces.

We also seized the opportunity to research under-sung artists like Sibyl Anikeef, one of eight photographers who documented California for the Federal Art Project. Ancestry.com came to the rescue in confirming Anikeef’s and other artists’ life dates and trajectories. Born in Chicago, Anikeef settled in Carmel in the 1930s with her husband Vasile, a Russian opera singer. Whether depicting agricultural laborers or twisted cypress trees along California’s coast, her work from this period is marked by a profound lyricism.

Ida Abelman, Countryside, 1935-1943

Collection SFMOMA, The United States General Services Administration, formerly Federal Works Agency, Works Projects Administration (WPA), allocation to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; photo: Don Ross.

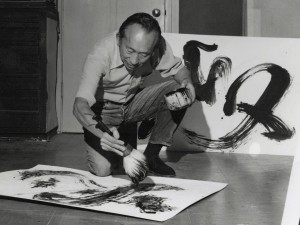

We used wall labels to flesh out the historical context and details of how the art programs operated. The label for Ida Abelman’s woodcut Countryside, for instance, relates that she was paid $23 per week for her work with the New York chapter of the Federal Art Project. A vitrine in the second room held a number of documentary photos of artists at work in media we could not otherwise display, like murals, mosaics and sculpture.

It was such a joy to work on this exhibition, which was a collaboration among early-career curators from different departments at SFMOMA. The icing on the cake was a tour for the Living New Deal! We hope that this exhilarating project leads to more New Deal curatorial projects in the future, as it remains a facet of our collection that deserves far more attention.

Learn More: https://www.vox.com/culture/21294431/new-deal-wpa-federal-art-project-coronavirus