The Roosevelts with King George IV and Queen Elizabeth of England aboard the USS Potomac, June 9, 1939

Courtesy, Wikimedia Commons

The Roosevelts with King George IV and Queen Elizabeth of England aboard the USS Potomac, June 9, 1939

Courtesy, Wikimedia Commons

FDR may be best remembered for leading the country though the Great Depression and winning the war against fascism, but some consider his repeal of Prohibition to be a pivotal achievement. Upon signing the 21st Amendment in 1933, (ending the nation’s thirteen years of illegal alcohol consumption), Roosevelt said, “I believe this would be a good time for a beer.” But, in fact, it was the gin martini that the president preferred. The Roosevelt Martini was testimony to his questionable mixology skills. Despite FDR’s late grandson, Curtis Roosevelt, describing FDR’s martinis as “the worst” tasting, FDR often enjoyed drinking more than one, which, at times, would inspire him to burst into his college fight song. Pinning down the exact recipe for the president’s signature drink is bit of a headache. A variety of recipes have been documented. (A common complaint is that the Roosevelt Martini is too heavy on the vermouth).

The Roosevelt Martini (Courtesy of Culinary Historians of Chicago)

Add ice to a mixing glass

Pour in 50ml of gin, 25ml vermouth (These amounts were sometimes reversed)

Splash of olive brine

Stir for 30 seconds

Strain into a cocktail glass

Garnish with an olive and lemon twist

(179 calories)

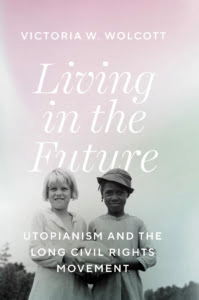

Victoria W. Wolcott, professor of History at the University at Buffalo College of Arts and Sciences, has been named the winner of the Living New Deal’s annual New Deal Book Award for 2022. Her book, Living in the Future: Utopianism and the Long Civil Rights Movement, (University of Chicago Press, 2022), explores the New Deal’s influence on the Civil Rights Movement.

Dr. Wolcott has published on a wide range of topics related to civil rights and social and racial justice. Her award-winning book examines how the emergence of experimental interracial communities in mid-20th-century America helped shape the views of civil rights leaders.

Living in the Future: Utopianism and the Long Civil Rights Movement, was unanimously chosen among eleven works nominated for this year’s award. A review committee of New Deal historians, chaired by Eric Rauchway, distinguished professor of History at the University of California, Davis, and author of Why the New Deal Matters, praised Wolcott’s book as “a profound and engaging study of interracial cooperative communities that experimented with new ways of life in the years of the Depression and New Deal. Their vision of new and better ways to live laid the foundations for the postwar Civil Rights movement.”

The Living New Deal launched the annual New Deal Book Award in 2021 to recognize and encourage nonfiction authorship about the New Deal, (1933-1942), an era defined by FDR’s presidency, the Great Depression and the nation’s entry into World War II. The $1,000 award will be presented to Dr. Wolcott on June 24, 2023 at the Annual Roosevelt Reading Festival, held at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, New York.

Richard Walker, director of the Living New Deal, expressed appreciation to all the nominees and the review committee. “It is immensely satisfying to see the high-quality scholarship being done on the New Deal, the significance of which still calls out to us ninety years later.”