FAP Art Sold as Scrap

New York curio shop owner Henry Roberts shows one of hundreds of FAP easel paintings he offered for sale at prices from $3 to $44 in 1944. He obtained the artworks from a scrap dealer who had purchased a job lot of “junk canvas” at a government surplus sale. Courtesy, LOC.gov Prints & Photos Division.

Like artifacts from a lost civilization, oral histories conducted by the Archives of American Art (AAA) in 1964-1965 have kept alive the thoughts and memories of New Deal artists, craftspeople and administrators for those of us in their future.

The interviews, conducted more than two decades after the New Deal’s art programs were dissolved, constitute an invaluable supplement to the vast body of material culture that these government-commissioned artists produced. Like the famous slave narratives gathered by the WPA’s Federal Writers Project from 1936 to 1938, the interviews with New Deal artists and administrators constitute an audio archaeology of those who have since passed on.

The Archives of American Art (AAA) was founded in Detroit in 1954 and ten years later launched an oral history initiative to document the arts programs of the Roosevelt administration. The AIA moved to Washington, D.C. in 1970 to become a unit of the Smithsonian Institution.

“The abrupt termination of the projects and the situation in Washington during the war made an orderly gathering together of the results of the projects impossible,” an article in the Archives’ Journal at the time explained. “We undertook the study because we believe that this is an area of America’s cultural history which is badly in need of clarification and that the time is right for a thorough, objective study of the New Deal and its art projects.”

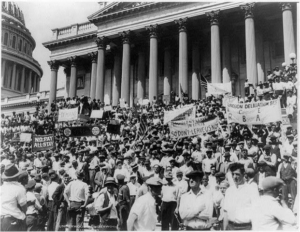

Beating the Chinese, “History of San Francisco,” by Anton Refregier, 1941

Conservatives in Congress wanted the mural series destroyed. Courtesy, LOC.

Time was of the essence thirty years after the federal art projects began. Many of the records and artworks had by then been scattered or burned. Some of those who had worked in the art projects had already died, but many were still in middle age and were cogent, opinionated and eager to pass on what they remembered.

Through the interviews one can hear the voices of of FSA photographers Russell Lee, Gordon Parks, and Arthur Rothstein, CCC artist and architect Victor Steinbrueck, Resettlement Administration head Rexford Tugwell, artist and photographer Ben Shahn, sculptor Mary Fuller McChesney and hundreds of other painters, sculptors, administrators and craftspeople.

Last year, the Archives launched an ambitious series of podcasts titled Articulated: Dispatches from the Archives of American Art. The first four episodes produced and narrated by the AAA’s Scholar for Oral History Ben Gillespie and Digital Experience Chief Michelle Herman featured Living New Deal team members Richard Walker, Barbara Bernstein and myself, as well as other scholars and archivists who use the interviews to learn about an unprecedented experiment in public arts patronage.

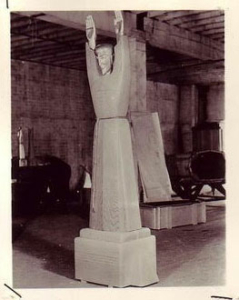

Sculptor Mary Fuller McChesney appears at her one-woman show at the Artists’ Guild Gallery, San Francisco, 1947. Courtesy, eichlernetwork.com.

The podcasts comprise interviews recorded in homes and studios under less-than-ideal conditions. The subjects are heard over a background of barking dogs, ringing telephones, children and typewriters. Memories that otherwise would have been lost nonetheless live on, captured by astute interviewers who were often themselves artists and even friends of their subjects, sometimes willing to lubricate their conversations with a gifted bottle of scotch.

I, myself, have used the extensive papers of the New Deal artist Anton Refregier at the AAA to learn more about his intentions for the immense historical cycle he painted for San Francisco’s Rincon Annex Post Office in 1946-1947, the last artwork produced under the federal arts programs.

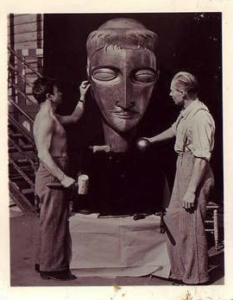

"Artists in WPA," by Moses Soyer, 1935

“Artists in WPA,” by Moses Soyer, 1935. Courtesy, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Employed by the Treasury Section of Fine Arts, Refregier considered the 28 murals depicting the history of California his masterpiece, so I also wanted to know his thoughts during an extraordinary 1953 hearing at which reactionary Congressmen sought to destroy the murals for what they asserted were its anti-American content.

The AAA has digitized five minutes of an interview with Refregier, so hearing his Russian-inflected voice at home was like encountering an old friend whom I had never met but knew well. “Ref” began by advocating for a renewed program of government-sponsored arts for public spaces like those that had once employed him.

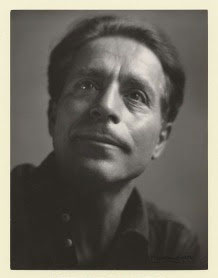

Arthur Rothstein, photographer for the New Deal’s Farm Security Administration (FSA).

Courtesy, Arthur Rothstein Legacy Project.

For its pioneering 1976 exhibition of New Deal art in California, the DeSaisset Museum at the University of Santa Clara secured an NEH grant to make video recordings of many New Deal artists alive at the time. Copies of those recordings are now in the possession of the AAA, which itself relies on grants and donations to carry on its work of transmitting knowledge to the present and future.

With sufficient funding, the AAA hopes to digitize those recordings so that anyone excavating the cultural archaeology of the New Deal will be able to see, as well as hear, the departed men and women who left the abundance of riches that survives.

Gray Brechin is a geographer and Project Scholar of the Living New Deal. He is the author of Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin.