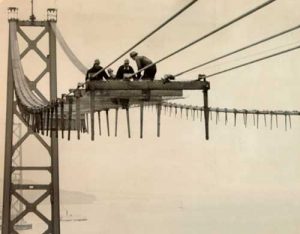

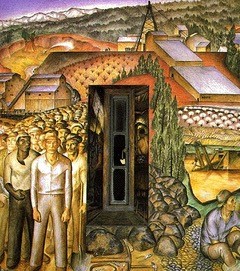

The Montgomery Block in 1862

The historic headquarters of San Francisco lawyers, financiers, writers, actors and artists.

Photo Credit: Public Domain

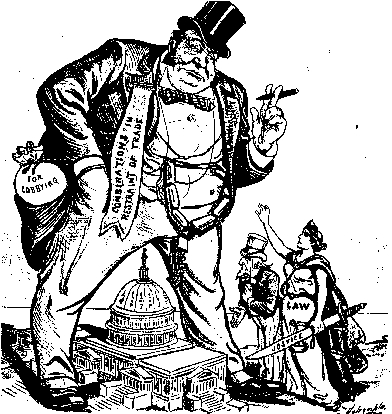

San Francisco poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, whose City Lights Books has been a touchstone of the city’s Bohemian culture for decades, once argued that his North Beach neighborhood “should be officially protected as a ‘historic district’, in the manner of the French Quarter in New Orleans, and thus shielded from commercial destruction such as was suffered by the old Montgomery Block building, the most famous literary and artistic structure in the West until it was replaced by the Transamerica Pyramid.”

When the 4-story Montgomery Block was completed in 1853, it was the tallest building west of the Mississippi River.

Transamerica Pyramid

The 48-story skyscraper replaced the Monkey Block

Photo Credit: Commons. Wikimedia.org

North Beach was then the “Barbary Coast” and teemed with brothels, dance halls, jazz clubs and saloons that accompanied the Gold Rush. Early on, 628 Montgomery Street held the offices of lawyers and financiers. Over the years, it housed an assortment of actors, artists and writers, including Mark Twain, Bret Harte, Ambrose Bierce, Robert Louis Stevenson, Jack London, George Sterling, and Emma Goldman. The Montgomery Block survived the earthquake and fire that destroyed much of the city in 1906. Though down-at-the-heel, it continued as a low-rent refuge through the Great Depression when as many as 75 artists and writers rented studios there for as little as $5 a week. The building was affectionately dubbed, “The Monkey Block.”

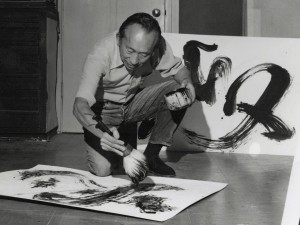

A number of artists at the Monkey Block got commissions from the federal government to paint the 26 murals at nearby Coit Tower—the first of hundreds of public art installations the New Deal would fund across the country. The political ferment that culminated in San Francisco’s General Strike in 1934 found expression in the murals, which delayed their public opening for fear of adding to the restiveness.

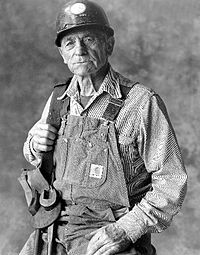

Edith Hamlin and Maynard Dixon

The artists met at the Monkey Block where they had studios down the hall from one another. They worked together on Edith’s second Federal Art Project mural at Mission High School.

Photo Credit: Courtesy SUU.org

The artists would unwind at the bars and restaurants of the surrounding neighborhood. A favorite watering hole was the Black Cat Café, located a few blocks downhill from the Monkey Block. Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Ralph Stackpole, Maynard Dixon, Dorothea Lange, Benny Bufano, Sargent Johnson and William Saroyan were part of the vibrant community of artists the New Deal fostered. Harry Hopkins, administrator of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), famously defended employment programs for artists and writers. “Hell, they’ve got to eat just like other people,” he said. Though the wages were low, the federal art programs enabled artists not only to eat but to develop their craft, through their proximity to and collaboration with fellow artists.

In her oral history, artist Shirley Staschen Triest recalled the working relationships that emerged at the Black Cat Cafe,“…it was where you’d hear about jobs, if there were any for artists and writers…It was where you’d go because that’s where everything was happening.”

California Industrial Scenes, Coit Tower

WPA Muralist John Langley Howard captured the restive mood of Depression-era workers.

Photo Credit: Courtesy FoundSF

Edith Hamlin, who, in addition to Coit Tower, painted murals at Mission High School, credited the WPA “as the beginning of my professional life as a muralist.” Sargent Johnson, whose sculptures adorn public spaces including what is now San Francisco’s Maritime National Historical Park, credits the WPA with his ability to continue as an artist. “The WPA was the best thing that ever happened to me because it gave me an incentive to keep on working, where at the time things looked pretty dreary.” Fellow sculptor Benny Bufano summed it up, “WPA’s Federal Art Project laid the foundation of a renaissance of art in America. It has freed American art.”

The New Deal left a legacy of public art in post offices, schools and public buildings. Once the gloom of the Depression lifted, many who had worked for the federal art programs went on to be some of the most important American artists of the 20th century.

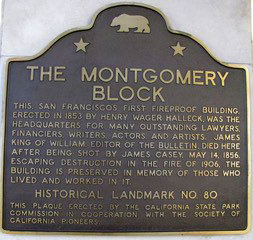

Plaque

The former site of the Monkey Block is a California Historical Landmark.

Photo Credit: Public Domain

Fostered by the New Deal, the community that came together at The Monkey Block offers a vivid and inspirational example that, if replicated, could again buoy the lives of artists, writers and performers and perhaps even lead to a new renaissance in American art.

Despite a movement to preserve it, the Monkey Block was demolished in 1959. The neighborhood’s rough-and-ready reputation was much diminished once the TransAmerica skyscraper rose from the rubble of what had for more than a century been a magnet for the city’s counterculture.