Ruth Gottstein, the artist’s daughter

Zakheim’s mural at Coit Tower depicts Ruth wearing a sailor suit.

My grandfather, Bernard Zakheim, was a seminal figure in the New Deal art world. He immigrated from Warsaw to New York in 1920, then made his way to San Francisco.

In the mid-1930s, Bernard coordinated the twenty-five muralists who created frescoes in San Francisco’s landmark Coit Tower. This was the largest of many endeavors sponsored by the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), which later became the Federal Art Project (FAP) that employed struggling artists nationwide during the Great Depression.

The Coit Tower murals, conceptualized by Zakheim, depict various scenes of life in California. Bernard’s fresco, “The Library,” shows a man removing a book by Karl Marx from a shelf. The mural includes an image of the artist’s daughter—my mother, Ruth, as a 12-year-old, wearing a blue-and-white sailor suit. At 97, she still tells the story of when she stood on Market Street with her father and witnessed striking dock workers in the days leading up to the San Francisco General Strike of 1934. The strike inspired some Coit Tower artists to include themes of labor unrest and economic inequity in the murals they painted there.

In 1935, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) commissioned Zakheim to paint a series of frescoes at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF). The eleven panels in Toland Hall graphically depict the evolution of medicine in California. Among the historical figures are Bridget “Biddy” Mason, a former slave who became a nurse, assisting Dr. John S. Griffin, one of California’s earliest trained physicians, in the treatment of a malaria patient.

Zakheim Murals at Toland Hall, UCSF

Bridget “Biddy” Mason, a former slave who became a nurse, assists Dr. John S. Griffin.

Photo Credit: Barbara Bernstein, New Deal Art Registry

The colossal undertaking of these Toland Hall murals may soon be undone as plans proceed to tear down the old hospital to make way for a new facility. The potential destruction of these murals comes amid assaults on other New Deal artworks when there is a change to the public spaces they embellish, or when controversy arises regarding their content. For instance, the threatened destruction of “The Life of Washington,” at George Washington High School by muralist Victor Arnautoff, also a WPA artist at Coit Tower, galvanized San Francisco’s arts community.

Bernard’s work has been threatened before: with neglect, water damage, political controversy and censorship. As an example, the lower half of a 1930s-era fresco he painted at the Alemany Emergency Hospital and Health Center in San Francisco was painted over in the 1950s. The fresco was saved six decades later when his son, Nathan Zakheim, expertly removed the paint.

Even the Coit Tower murals, a major city attraction, were neglected for years. Legislation approved by the voters saved the murals and upgraded the building.

From both an artistic and historical perspective, the Toland Hall murals are irreplaceable. Like many New Deal works, they are a window on the past. Importantly, they are remnants of an era when government exalted and funded the arts. Given this most recent threat, another rescue campaign is underway. As a family, we continue to do all we can to ensure the murals’ survival so that future generations can appreciate and learn from them.

Watch: Tour the Toland Hall murals tour with Dr. Chauncey Leake, 1976 (45 minutes)

Superstitious Medicine and Rational Medicine

WPA artist Bernard Zakheim studied with Diego Rivera, whose influence can been seen in the Toland Hall murals.

Photo Credit: Barbara Bernstein, New Deal Art Registry

Zakheim Murals

Viewing murals at Toland Hall at UCSF, left to right: F. Stanley Durie, Superintendent of UC Hospital, Dr. William E. Carter, Phyllis Wrightson, Joseph Allen, State Director of WPA Federal Art Project, Bernard Zakheim (ca. 1939) Source

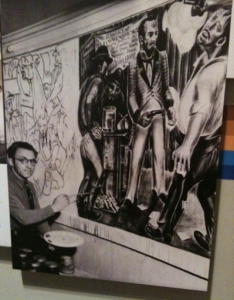

Zakheim at work, 1937

The artist at Toland Hall, University of California Hospital

Photo Credit: Courtesy, Adam Gottstein