Green New Dealers

Organizers are mobilizing youth to put pressure on Congress Source

In a radical departure from business as usual, talk of a “New Deal” has lately been reverberating through the halls of the nation’s Capitol. Newly elected Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass) have introduced a resolution for a Green New Deal that is making headlines and rapidly gaining public support.

The Green New Deal resolution, introduced in early February, cites catastrophic repercussions for the economy, the environment, humans, and wildlife as a result of climate change. The Green New Deal is a package of federal programs and investments to transition the nation from fossil fuels to 100 percent clean, renewable energy over 10 years, creating millions of high-wage jobs in the process. The details are still to come.

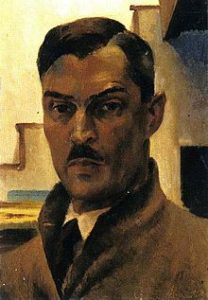

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

Announcing the Green New Deal resolution on Feb 7

Photo Credit: OaklandNews

The original New Deal offers a blueprint. Like its proposed green offspring, the New Deal was a massive response to an unprecedented national emergency. The government took multiple and experimental approaches to the economic, social and environmental crises of the Great Depression.

One of the first and most popular programs, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), begun in 1933, deployed millions of men over ten years to improve the environment. The “first responders” of their day, the CCC men fought wildfires and epic floods, planted billions of trees, stabilized soils in the Dust Bowl and elsewhere, and developed a system of national refuges to sustain diminishing wildlife.

Millions found work through federal programs to modernize America’s “commons,” building roads, bridges, dams, housing, schools, hospitals, parks, and playgrounds.

CCC at work

Installing phone lines at Logan Pass, Montana, 1938

Photo Credit: National Park Service

While the New Deal brought jobs and enhancements to cities, towns and rural nationwide, many minority communities were left behind. African Americans, domestic, and agricultural workers were often excluded in exchange for the support of Republicans and Dixiecrats in Congress who held the purse strings.

Recognizing this failure, the Green New Deal resolution is explicitly inclusive in its aim “to promote justice and equity by stopping current, preventing future, and repairing historic oppression of indigenous communities, communities of color, migrant communities, deindustrialized communities, depopulated rural communities, the poor, low-income workers, women, the elderly, the unhoused, people with disabilities, and youth.”

More than sixty progressive House members and several 2020 presidential candidates have already declared their support for a Green New Deal, as have several labor unions and environmental organizations. The trillion-dollar question is how to pay for it. A carbon tax, raising taxes on the ultra wealthy, and redirecting subsidies away from fossil fuels to renewable energy, are among the ideas.

WPA sewer project

Men laying pipes for the city of San Diego, California, 1935 Source

Not surprisingly, Republicans dismiss the Green New Deal, branding it “socialist,” “reckless,” “expensive,” and “unattainable.” Oklahoma Rep. Markwayne Mullin pronounced: “The Green New Deal, like Medicare- for-All and tuition-free college, is nothing but an empty promise that leaves American taxpayers on the hook.”

But climate activists point out that a Green New Deal would be far less costly than the climate disasters, pollution, and health problems that come from fossil fuels. Polls show growing public support for a Green New Deal. A December 2018 poll by Yale University’s Program on Climate Change Communication, found more than 90 percent of Democrats and 57 percent of self-identified “conservative Republicans” support a Green New Deal.

WPA emblem

Posted at work sites nationwide during the Great Depression

Organizers want to make the resolution a litmus test for those running for office in 2020. The Sunrise Movement is one of a growing number of grassroots groups mobilizing support among the nation’s youth. Its stated goal, “To build the movement for a Green New Deal.” Their social media campaign enjoins supporters to “turn up the heat” on Congress.

Sign the petition for a Green New Deal

The Living New Deal website’s new page on the Green New Deal describes ten

principles that led to the success of the original New Deal.

Susan Ives is communications director for the Living New Deal and editor of the Living New Deal newsletter.