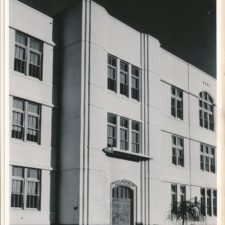

George Washington High School

Designed by famed San Francisco architect Timothy Pflueger, the art deco-style school opened in 1936. The stadium, auditorium and gymnasium were added in 1940.

Photo by Robert Dawson, Living New Deal.

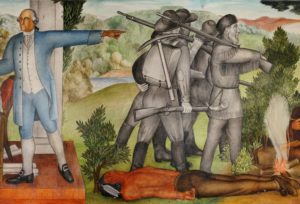

WPA artist Victor Arnautoff’s controversial mural, “Life of Washington,” has been a lightning rod for controversy ever since it was completed in 1936.

The 1600-foot fresco covering the walls and ceiling of the main entryway at San Francisco’s George Washington High School narrowly survived a recent challenge when some students and parents asserted that the mural traumatizes students and demanded that the school board “Paint it down.”

Historians, writers, artists and some tribal leaders defended the immense artwork, which depicts Washington among enslaved Blacks and standing over a slain American Indian. They counter that the Ukrainian-born Arnautoff, an avowed Communist, intended the murals as a thinly veiled critique of America’s racism.

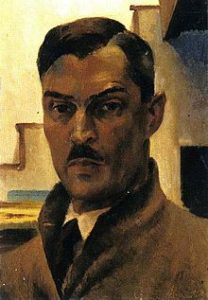

Self portrait, Victor Arnautoff, 1896-1979

Arnautoff worked with Diego Rivera in Mexico in the 1930s and went on to produce a number of murals for the WPA. He taught art at Stanford University but was fired for his political views and returned to Ukraine. Courtesy Helfinfinearts.com.

Rather than paint over the mural, in 2019 the Board of Education voted unanimously to conceal the mural behind a curtain—at a cost to the San Francisco Unified School District of some $600,000. After the decision, hundreds of people squeezed into the school’s main lobby for a rare public viewing to catch a final glimpse of the 13-panel painting.

The 6,500-member George Washington High School Alumni Association filed a lawsuit to protect the mural and in 2021 the California Superior Court ruled that the school board had violated the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and stopped the board from destroying or covering up the historic artwork.

A few months later, San Franciscans recalled three school board members who had voted to censor the murals. Last summer, the newly installed school board rescinded the previous board’s decision. But the debate continues.

Dewey Crumpler

Crumpler painted the “response murals” to Arnautoff’s “Life of Washington” mural at George Washington High School in 1974.

Screenshot from Youtube video.

Following the court ruling, Lope Yap, Jr., vice president of the school’s alumni association, thanked supporters. “Arnautoff takes a real perspective on the dark side of Washington, not [just] his great accomplishments, but to say, we’re not perfect,” “Maybe it’s painful, but what’s not accurate about this?”

“Any attempt to destroy Arnautoff’s murals has been thwarted— for the time being,” he added.

Paloma Flores, a member of the Pit-River Nation and former coordinator of the District’s Indian Education Program, disagrees. “It’s not a matter of censorship, it’s a matter of human right: the right to learn without hostile environments. Even the best intentions do harm.”

Washington at Mt. Vernon

Critics point to the mural’s depiction of slavery as racist. Others maintain Arnautoff’s social commentary—America’s “founding father” was dependent on enslaved labor for his wealth. Photo by Richard Evans, Living New Deal. (click to enlarge)

Conflicts over Arnautoff’s “Life of Washington” date to the 1960s when Black students at the school criticized the mural for its limited view of Black history as a story of enslavement and victimization. Their activism resulted in “response murals,” painted at the school by a young Black artist, Dewey Crumpler.

“Murals exist to teach and to speak about our uncomfortable history,” Crumpler maintains. “Arnautoff attempted to give us the clarity of our history, as all great works should do.”

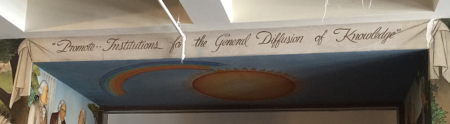

“The march of the white race from the Atlantic to the Pacific”

According to Arnautoff’s biographer, Robert Cherney, this panel reveals the artist’s condemnation of the killing and dispossession of America’s First People. Photo by Richard Evans, Living New Deal. (click to enlarge)

“This high school is home to a national art history treasure,” says Yap. “Let’s protect it and learn from it.”

The alumni association is pursuing landmark status for the artworks and the high school, built in 1936 with the help of the New Deal’s Public Works Administration (PWA).

“Athletics”

Detail of a frieze by Sargent Johnson. The school contains a trove of New Deal artworks: bas reliefs sculpted by Robert Boardman Howard; monumental friezes by Sargent Johnson and murals by Lucien LaBaudt, Gordon Langdon and Robert Stackpole. Photo by Barbara Bernstein, Living New Deal.

Learn more:

Arnautoff’s biographer, Robert Cherney, explains the “Life of Washington” murals

A new documentary, Town Destroyer, recounts the controversy over the George Washington High School murals. WATCH THE TRAILER (2 minutes)

Watch: Artist Dewey Crumpler discusses his “response murals.” (3 minutes)