Rewriting America, a symposium held at the American Folkways Center on June 16, 2023. Photo by Susan DeMasi.

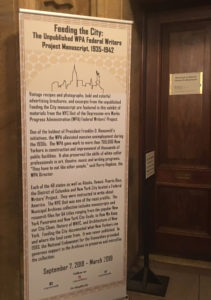

The Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), a unique New Deal program begun in 1935, provided jobs to thousands; published scores of books (including the celebrated WPA American Guide series); kickstarted the careers of such legendary authors as Richard Wright and May Swenson; and collected oral histories from immigrants and formerly enslaved people. In June, a symposium at the Library of Congress (LOC), “Rewriting America: Reconsidering the Federal Writers’ Project 80 Years Later,” celebrated the FWP’s legacy and continued influence.

It’s fitting that the symposium took place at the Library of Congress. When the FWP closed down in 1943 many of its documents were deposited there. Eighty years later, the collection, consisting of thousands of archival boxes and digitized materials, continues to be mined by historians, writers, educators, documentarians, and folklorists.

During its 8-year run, the FWP produced 275 books, 700 pamphlets, and 340 “issuances” (articles, leaflets and radio scripts.). Courtesy, NARA.

Hosted by the American Folklife Center, a special collections division in the LOC, the symposium’s agenda centered around the recently published “Rewriting America: New Essays on the Federal Writers’ Project (University of Massachusetts Press, 2022), edited by Sara Rutkowski. Speakers included some of the book’s contributing authors, as well as other researchers and writers in the field of FWP studies and oral history. Guha Shankar, American Folklife Center program specialist, organized the program along with FWP scholars Rutkowski, Deborah Mutnick, David Taylor, Jerry Hirsch, and Benji de la Piedra.

William Colbert, Age 93. Alabama

The FWP’s Slave Narrative Collection documented over 2,300 first-person accounts of former slaves across 17 states. Courtesy, LOC.

Presentations centered on the politics and vision of the FWP; contemporary undertakings that are making use of the LOC’s FWP materials, including new readings of the narratives of enslaved African Americans; research into Asian American and Mexican American FWP writers; an upcoming FWP podcast; and a New York City-based multimedia project about Covid-19, inspired by the original FWP.

With the study of oral history so prominent in FWP studies, an internationally renowned oral historian, Alessandro Portelli, gave the keynote address, which “situated the FWP within the trajectory of the field of oral history and its intersection with current public humanities projects,” said LOC’s Shankar.

There was discussion about pending federal legislation introduced by Representative Ted Lieu (D-California), calling for a 21st Century Federal Writers’ Project. As proposed, the revived FWP would be run by the Department of Labor. As with the original FWP, all works created under the program would be archived at the Library of Congress and made widely available to the public.

American Guides poster

The FWP’s American Guide Series published histories, automobile travel routes, photographs, maps, and descriptions of the diverse cultures and geography of all 48 states, as well as several cities and territories.

Courtesy, Work Projects Administration Poster Collection – Library of Congress.

The American Folklife Center (AFC) is designated the national center for folklife documentation and research. Its archive encompasses millions of items of ethnographic and historical documentation from the U.S. and around the world.

The symposium was hosted by the AFC, with support from by the American Folklore Society, the Oral History Association, and the Professional Staff Congress: City University of New York. The Living New Deal contributed copies of its Map and Guide to the New Deal in Washington, DC, featuring 500 New Deal sites and a self-guided walking tour of the National Mall.

For more information about the symposium:

“Re-writing America”: AFC Symposium on the Federal Writers’ Project, by Guha Shankar