FDR speaks at Greenbelt

The president visited the partially completed town on November 13, 1936. “I have reviewed the plans but the reality exceeds my expectation,” he said. Pictured L-R: Rex Tugwell, head of the Resettlement Administration; President Roosevelt; and Wallace Richards, Executive Officer, Greenbelt Project. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

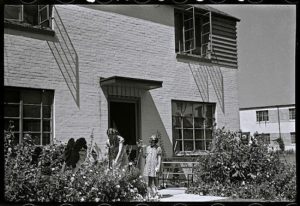

Joblessness and homelessness during the Great Depression led the federal government in 1935 to demonstrate how modest, well-built homes could improve the lives of ordinary Americans if these homes were located, designed and managed to promote “family and community life.” The plan was described in a 1937 pamphlet, Greenbelt Towns, published by the New Deal’s Resettlement Administration.

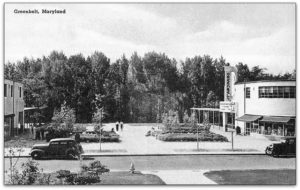

Forests were essential to several New Deal initiatives, including this planned-community program. Of the three greenbelt towns the federal government built, Greenbelt, Maryland, most strongly expressed the idea of a “belt of green.” The surrounding forests, parks, farms and gardens were intended to prevent encroachment from outside development and

Photo taken from the Goodyear Blimp in May, 1936, shows the forests and fields surrounding the town. While much of the town’s original green space has since been developed, and the mix of tree species has changed, eighty years on, a “belt of green,” now preserved, still defines the town. Photo annotations by O. Kelley. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

strengthen the bonds of community by encouraging residents to spend their leisure time in town with the natural world a short walk from their front doors. Greenbelt was shaped by the Garden City ideals of Ebenezer Howard and Clarence Stein. Within a Garden City, a neighborhood was defined as having homes within a half-mile walk from a central cluster of public buildings to include an elementary school or community center. Buildings and footpaths were embedded in forest and grassy common areas where residents could connect with their neighbors. Stein wrote about this aspect of Greenbelt in Toward New Towns for America, and his struggle to make these ideas stick in the sometimes chaotic and rushed atmosphere of the New Deal.

FDR motorcade touring the Greenbelt Lake dam. The forested tract in the background has been owned by the town since the federal government sold the land in 1950–1954. It was added to the Greenbelt Forest Preserve in 2007. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Foreshadowing Greenbelt’s future, FDR in his 1938 introduction to Public Papers and Addresses, described the pendulum of participatory democracy, whereby the wealthy few exercise the lion’s share of political power and then, a few decades later, popular movements would force the government to accommodate the people’s needs and desires. Broadly speaking, the pendulum swung toward participatory democracy during the Great Depression in the form of protests, labor organizing and federal legislation shaped by the demands of the grassroots.

The town’s iconic Mother and Child sculpture, by WPA artist Lenore Thomas, 1937. Footpaths wend through Greenbelt’s landscape, in keeping with Garden City planning principles of using green space to nurture a sense of community. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

The original plan for the Greenbelt envisioned cooperative ownership of community assets—and idea that lives on today. Cooperatives own Greenbelt’s New Deal-era townhomes and 87 acres of protected woodland, the grocery store and the town’s weekly newspaper, founded in 1937.

For decades, Greenbelt residents have fought to preserve their town’s namesake. From 1950–1954, the federal government carried out part of the greenbelt plan that called for selling much of the land to a housing cooperative and the town government. In the 1960s, with sprawl radiating from Washington DC, Greenbelt residents elected a conservation-minded city council and began buying back land the housing cooperative had sold to developers. By 1989, the city owned a contiguous 245-acre forested tract of the original green belt and designated it the Greenbelt Forest Preserve. It protects century-old trees and a variety of habitats—vernal pools, wetlands, oak-hickory stands and a heath ecosystem similar to New Jersey’s pine barrens.

In 1997, Greenbelt’s New Deal-era buildings and adjacent forests became a National Historic Landmark.

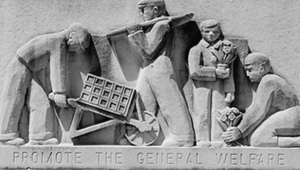

"Promote the General Welfare" by Lenore Thomas

Public artworks throughout Greenbelt reflect social and economic themes, an interest in the common man and the pursuit of democratic ideals. The Center School exterior features bas reliefs inspired by nature and the Preamble to the US Constitution. Photo by Arthur Rothstein, 1937. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Inspired by their town’s founding ideals, Greenbelt’s residents continue to resist threats to their community and its greenbelt. Residents have organized to oppose a high-speed rail project that imperils the Forest Preserve and natural areas to the north, and are pushing elected officials to defeat the proposed plan. It’s the sort of citizen activism Greenbelt’s New Deal planners envisioned from the start.”

Learn more:

greenbeltmuseum.org

https://livingnewdeal.org/projects/city-of-greenbelt-greenbelt-md/

FDR and the Environment, Editors Henry L. Henderson and David B. Woolner (2005); Douglas Brinkley’s Rightful Heritage (2016). “Clarence Stein and the Greenbelt Towns,” Journal of the Am. Planning Assoc., (1990); and The New Deal in the Suburbs, a history of the Greenbelt town program, 1935-1954, by Tracy Augur.