Old Greenbelt Theater

The theater opened on September 21, 1938, with Little Miss Broadway, a film starring Shirley Temple. Admission was 30 cents for adults and 15 cents for children. Photo Courtesy, Maryland Humanities.

Greenbelt, Maryland will celebrate the 90th anniversary of FDR’s New Deal (1933-1942) at the19th Utopia Film Festival to be held October 20-22 at the city’s historic Old Greenbelt Theatre. This year’s festival will include a presentation of the “New Deal Spirit Award.” The award recognizes independent films that reflect New Deal ideals.

Since 2005, the annual festival has showcased films about community building, cultural diversity, social and economic concerns and environmental issues. Projects eligible for the New Deal Spirit Award fall into three categories: full-length documentary or feature films (no longer than 90 minutes); short documentary or feature films (no longer than 30 minutes); and animation. Festival planners invite filmmakers and animators to submit their work for consideration by August 4, 2023.

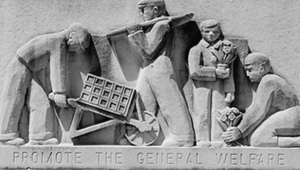

Plaque at the Greenbelt Theater

The theater embodies the community values of safe, healthy, affordable housing for all citizens. Photo by Susan Ives.

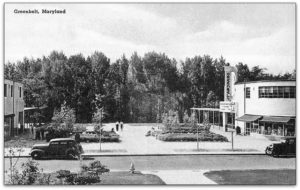

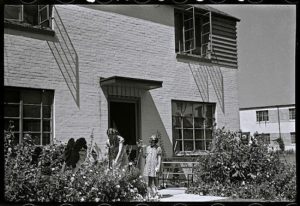

The festival takes its name from the “utopian” origins of so-called green towns, planned and built by the federal government to provide affordable housing for families during the Great Depression. The towns, inspired by the garden city theory of urban planning, were ringed by forests and farms and designed to foster healthy living and community solidarity by incorporating walking paths, playgrounds and common areas.

Greenbelt, twelve miles northeast of Washington, DC, was built by WPA workers in 1937. Its residents were screened for their willingness to engage in the community. Greenbelt residents established cooperatives—community-run enterprises. The Greenbelt grocery and the newspaper, originally named “The Greenbelt Cooperator,” remain co-ops to this day.

Rexford Tugwell, the head of the New Deal Resettlement Administration, had envisioned hundreds of green towns. But critics derided them as “utopian.” Tugwell was dubbed “Rex the Red,” by some in Congress for his egalitarian views. Only three green towns were built—Greenbelt, Maryland; Greendale, Wisconsin and Greenhills, Ohio.

Compared with its sister towns, Greenbelt has endured with few alterations.

The town’s center, Old Greenbelt, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1997. Today, it’s considered a planning landmark and attracts visitors from around the world.

The Utopia Film Festival is run entirely by volunteers. Chris Haley, the executive director, also is director of the Study of the Legacy of Slavery in Maryland at the Maryland State Archives (and is the nephew of Alex Haley, author of “Roots”). Chris shared his thoughts on the New Deal at 90, the New Deal Spirit Award and the racial segregation in Greenbelt’s past.

“I think, especially given where we are as a nation right now, this award will remind us of what the New Deal represented—better ways to live if we act together as one community. Granted, the (New Deal’s) initial implementation, highly segregated, didn’t create that reality. However, the ideal is one we should always strive to achieve. The Utopia Film Festival wants to remind and recognize that spirit in film.”

The Utopia Film Festival is a project of the nonprofit Greenbelt Access Television, the festival’s primary sponsor. For information about the New Deal Spirit Award, contact the festival committee: [email protected].