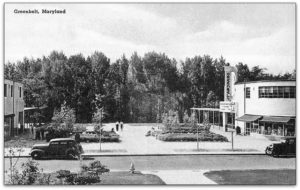

Greenbelt sign, 1937

The Greenbelt housing project was seen as a social experiment

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

The first of three greenbelt towns built and owned by the federal government during the Great Depression, Greenbelt, Maryland, ten miles north of Washington, D.C. was considered “utopian” when it opened in 1937.

Greenbelt’s residents had to overcome many obstacles from the start, and today a new threat is bearing down on the New Deal town.

Maryland’s Governor Larry Hogan, state legislators, and the private company Northeast MAGLEV, are hawking a public-private partnership to build a high-speed train, between D.C and New York that could impact this historic community.

FDR and Wallace Richards, 1936

Richards, coordinator for the Greenbelt project, shows plans to President Roosevelt

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

Home to 23,000 residents, Greenbelt is the legacy of Rexford Tugwell, a friend and advisor whom FDR appointed to head the short-lived Resettlement Administration (RA). Tugwell, inspired by England’s Garden City movement—a turning point in urban planning—envisioned hundreds of “greenbelt towns” around the country. Surrounded by greenbelts of forests and farms, they were meant to provide affordable homes with easy access to jobs in nearby cities.

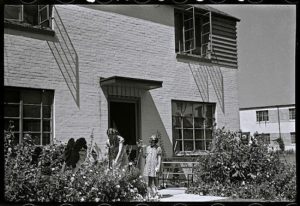

The affordable houses, landscaping, parks, playgrounds, schools, and civic buildings were designed to nurture a sense of community. Applicants for residency were screened based on income, occupation, and a willingness to become involved in community activities. Much of the towns’ business was conducted through cooperatives, to the dismay of conservatives in Congress who nicknamed Tugwell “Rex the Red.”

Congress soon pared plans for the greenbelt towns and delayed funding. Lacking the heavy construction equipment they needed to break ground, WPA workers used picks and shovels.

Ultimately just three towns, Greenhills, Ohio; Greendale, Wisconsin; and Greenbelt, Maryland were completed. A fourth town, planned for New Jersey, was summarily cancelled.

House and Garden, 1938

Greenbelt offers apartments and single-family homes like these English-style row houses with pitched slate roofs.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

Over the years, Greenbelt, Maryland has suffered fewer alterations than its sister towns, but “progress” has taken a toll. Despite residents’ opposition to the Baltimore–Washington Parkway it was built through the greenbelt in 1954. The Capital Beltway also pushed through the middle of the greenbelt in the 1960s. Thanks to the Committee to Save the Green Belt and other advocates, the city reacquired 230 acres of the original greenbelt that had been sold to developers in the 1950s and established the Greenbelt Forest Preserve to permanently protect the land. In 1997 Greenbelt was designated a National Historic Landmark.

In 2017, plans emerged for a high-speed MAGLEV (magnetic-levitation) train. Two routes are under consideration. One is east of town and would tunnel under Eleanor Roosevelt High School and several neighborhoods. The other, on the west side of town, would mostly follow the Parkway, tunneling below the town to emerge in the Greenbelt Forest Preserve or possibly north of the town.

The proposed train would cut the 32-minute Amtrak ride from Baltimore to D.C by 17 minutes.

Greenbelt Pool, 1939

Parks, playgrounds and recreation facilities have been part of the community from the start.

Photo Credit: Marian Wolcott Post, Library of Congress

Opponents up and down the proposed corridor point to the project’s $10 billion price tag and the cost overruns that have plagued other high-speed rail projects, leaving taxpayers on the hook.

The federal government has provided $27.8 million for an Environmental Impact Study, scheduled for completion in January 2019.

Meanwhile, Northeast Maglev has acquired the ability to use eminent domain to build the track.

What you can do: Take Action.

The City also posted information on how to oppose.

“Mother and Child” by Lenore Thomas, 1938

WPA artists adorned the Commons and public buildings.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

Greenbelt Elementary School, 1937

The art deco building became the community center after a new school was built in the 1990s.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress