While doing research for their 2011 guidebook to the Civilian Conservation Corps’ work in the nation’s parks, Our Mark on This Land, Ren and Helen Davis searched through thousands of historic photographs at the National Park Service’s photography archive in Charles Town, West Virginia. The collection included striking images of the parks during the 1930s. The photographs were simply credited “National Park Service,” leaving the Davises to wonder who had taken them.

While doing research for their 2011 guidebook to the Civilian Conservation Corps’ work in the nation’s parks, Our Mark on This Land, Ren and Helen Davis searched through thousands of historic photographs at the National Park Service’s photography archive in Charles Town, West Virginia. The collection included striking images of the parks during the 1930s. The photographs were simply credited “National Park Service,” leaving the Davises to wonder who had taken them.

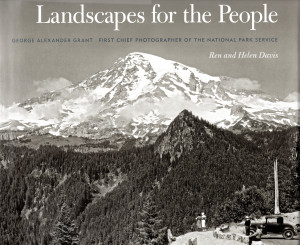

The answer led them to more years of research, and ultimately to write the award-winning biography of George Alexander Grant, the first chief photographer for the National Park Service.

George Grant’s 25-year career as the Park Service’s official photographer resulted in more than 30,000 photographs of national parks. Like his much-heralded contemporaries Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Eliot Porter, Grant wielded medium- and large-format field cameras and weighty tripods through rugged country. Grant often processed his images in the back of a panel truck, dubbed “the hearse,” that served as his darkroom and home away from home while on assignment.

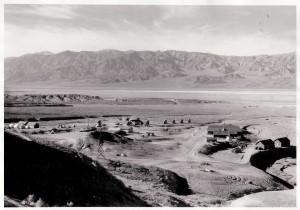

Grant’s job took him to more than a hundred national parks, monuments, historic sites, and battlefields. His dedication, stamina, and exacting standards produced images capable of persuading Congress to fund, and the public to support, the expanding National Park Service.

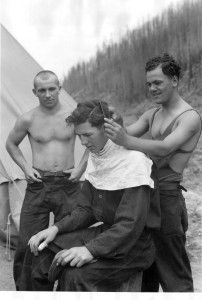

It’s ironic that the worst of times, the Great Depression, would come to be known as the golden age of parks. State and national parks were vastly expanded during the New Deal, developed largely with manpower provided by the CCC. Many of Grant’s photographs document life in the CCC camps and the men who built the roads, bridges, museums, and facilities that transformed the parks from playgrounds for the rich to places welcoming to all Americans.

Grant’s photographs continued to promote the parks into the early 1940s, portraying Americans camping, picnicking, and hiking amidst natural splendor. After World War II, Grant’s work extended to photographing the construction of dams on the upper Missouri River, including documenting archaeological sites soon to be under water.

Landscapes for the People, with more than 170 exquisitely reproduced photographs, is an invaluable record of the shaping of the national parks and the modernizing of a nation. As important, thanks the Davises, a forgotten elder of American landscape photography is finally getting his due.