At the end of Mexico’s long revolution (1910-1920), a time of stability emerged. The newly elected government of President Alvero Obregón dedicated funds for construction, education and the arts.

Postmaster James M. Allen and WPA artists Mitchell Siporin, Edgar Britton, and Edward Millman examine a small-scale study for their Decatur, Illinois post office murals.

Courtesy, Illinois Periodicals Online.

With the aid of his Minister of Education José Vasconcelos, Obregón launched a national initiative to build schools and employed artists to decorate the walls with murals. From this program, three leading talents emerged, often referred to as Los Tres Grandes: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Employing modernist imagery with social justice themes, these multiple mural projects celebrated Mexico’s indigenous heritage and promoted Socialist views held by many artists and much of the world art that time.

Mexican art had a profound effect on young American artists and can be seen in the murals, prints, photographs and easel paintings created under Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal art programs.

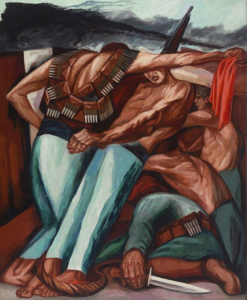

The Barricade, 1931

By José Clemente Orozco. The Mexican Muralist movement asserted the importance of large-scale public art. Orozco’s social realism, solidarity with workers and the struggle for freedom and justice are themes often seen in works by WPA muralists. Courtesy, MOMA.

Fresco Detail, Central Post Office Building, St. Louis, Missouri, 1941

By Edward Millman. The largest single commission by the Treasury Section of Fine Arts, nine murals depicting the history of Missouri, by WPA artists Edward Millman and Mitchell Siporin, reflect the strong influence of Mexican muralists. Courtesy, Swann Galleries.

By the end of Obregón’s 4-year term as president funding for Mexico’s mural projects had declined. Los Tres Grandes sought mural commissions in the United States, beginning with Orozco, who completed the first of his three American murals, Prometheus, at Pomona College in Claremont, California in 1930.

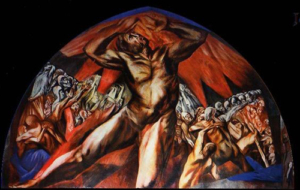

"Prometheus," 1930

Jose Clemente Orozco’s fresco mural at Pomona College depicts the Greek Titan Prometheus stealing fire from the heavens to give to humans was the first modern fresco in the United States. Courtesy, Wikipedia.

Jackson Pollock, who worked for the WPA Federal Art Project from 1938 to 1942, traveled to California to see Orozco’s mural and was so inspired he kept an image of Prometheus in his New York studio. Mitchell Siporin and Edward Millman also studied the murals of Orozco before starting their mural series for the St. Louis, Missouri, Post Office. The resulting nine frescos were the largest single mural project commissioned under the Treasury Section for a post office.

Between 1930 and 1933, Diego Rivera created murals in San Francisco, Detroit and New York City. His fresco series, Detroit Industry Murals, completed in 1933 for the Detroit Institute of Art, consists of 27 panels spanning four walls and depicts industry and technology as the indigenous culture of Detroit. Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads, 1933, commissioned by the Rockefeller family for Rockefeller Center, was famously destroyed after Rivera refused to remove the image of Vladimir Lenin from the composition.

Rivera would later recreate the mural in Mexico City. Not only did Rivera influence American artists through his artwork and activism, he also taught several artists that would go on to use their learned fresco craft under the employ of the WPA, including: Seymour Fogel, Emmy Lou Packard, Thelma Johnson Streat, Mine Okubo, and Edna Wolff.

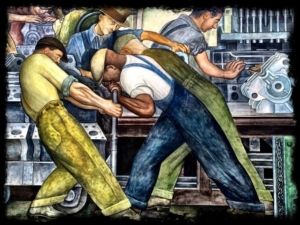

"Industry Murals," 1932

Famed muralist Diego Rivera painted the frescoes surrounding the courtyard at the Detroit Institute of Art. He considered the mural series his finest work.

Photo: Susan Ives.

"Automobile Industry," 1941

WPA artist William Gropper, a student of Diego Rivera, painted this mural at the Northwestern Branch Postal Station in Detroit.It now resides at the Wayne State University Student Center. Courtesy, NewDealArtRegistry.org

The influence of Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros can clearly be seen in works by such New Deal artists as Thomas Hart Benton, Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston, Ben Shahn, William Gropper, Aaron Douglas and Jacob Lawrence.

David Alfaro Siqueiros, the most politically progressive of the “Tres Grandes,” would complete only one mural in America. América Tropical: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos (“Tropical America: Oppressed and Destroyed by Imperialism”) was completed on a 2nd floor exterior wall of the Italian Hall in Los Angeles in 1932. Within six months the portion of the mural visible from the street was whitewashed by conservative city authorities. In 2012, the work was reintroduced to the public after an extensive restoration and renovation funded by the Getty Foundation.

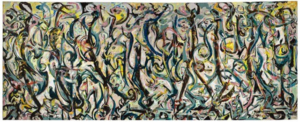

Mural, 1943

Jackson Pollack, who studied with Siqueiros in New York, was influenced by the muralist’s unconventional use of industrial-grade paints and materials. Courtesy, Guggenheim.org.

Siqueiros’ unconventional use of industrial-grade paints and materials influenced Jackson Pollock and other modernist American painters who studied under Siqueiros in his Experimental Workshop, which he opened in New York City in 1936.

The Mexican muralists inspired a generation of New Deal artists whose work helped to form a modern American identity, one rooted in pride and tenacity, expressing hope through the imagery of hardship.