A WPA worker receives a paycheck, 1939.

Priority employment in the WPA went to those in need of relief.

Photo Credit: Courtesy National Archives

In his first Inaugural Address in 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt confronted the Great Depression with a promise of “action and action now.” Fast forward 88 years. In the face of a worsening pandemic and a sliding economy, Biden made the same pledge: “In this moment of crisis,” he said, “we have to act now…. we cannot afford inaction.”

Biden has moved quickly to propose a supplement to Unemployment Insurance (UI), bigger cash tax credits and an extra one-time payout of $1,400. Many unemployed adults, however, don’t qualify for UI. Jobless workers without children will get little-to-no help from a larger Earned Income Tax Credit or Child Tax Credit. The extra $1,400 will only stretch so far.

President Franklin Roosevelt and Secretary of Commerce Harry Hopkins

A close advisor to FDR, Hopkins was an architect of New Deal relief programs.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Library of Congress

What Biden has not yet proposed is a large, federally subsidized jobs program. His “Build Back Better” plan calls for 18 million good paying jobs, mostly in infrastructure. But he has not yet presented Congress with specific legislation. The nation needs action and action now.

The New Deal’s jobs programs show the way. From the start, Roosevelt made clear that his “primary task” was getting unemployed Americans back to work.

In his First 100 Days, FDR created the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and tapped Harry Hopkins to run it. He told the Washington newcomer: Get immediate and adequate relief to the unemployed, and pay no attention to politics or politicians. Three days later, Hopkins got to work and within an hour sent $5 million in cash relief to four million destitute American families.

Hopkins immediately recognized, however, that unemployed workers did not want a handout. They wanted jobs. FERA soon offered not just cash relief, but the opportunity to earn the same amount through work relief. Instead of a handout, it provided the dignity of employment.

Unemployment office, 1938

“Jobless men lined up for the first time in California to file claims for Unemployment Compensation.”

Photo Credit: Photo by Dorothea Lange. Courtesy, Social Security Administration

In November 1933, Roosevelt and Hopkins went much further. The experimental Civil Works Administration (CWA) offered the unemployed real jobs that paid the prevailing wage. Within a month, the CWA hired four million to carry out over 4,000 projects.

The program was temporary. Hopkins regretted its end in 1934. He saw the CWA as proof that unemployed Americans wanted to work and as the best model for providing them jobs until they could be absorbed into the regular labor market. With the CWA in mind, Hopkins lobbied for an Employment Assurance Corporation to serve as the employer of last resort.

The Social Security Act of 1935 lacked a permanent job assurance program. Nevertheless, FDR, who disfavored what he called “the dole,” told Congress: “Work must be found for able-bodied but destitute workers.”

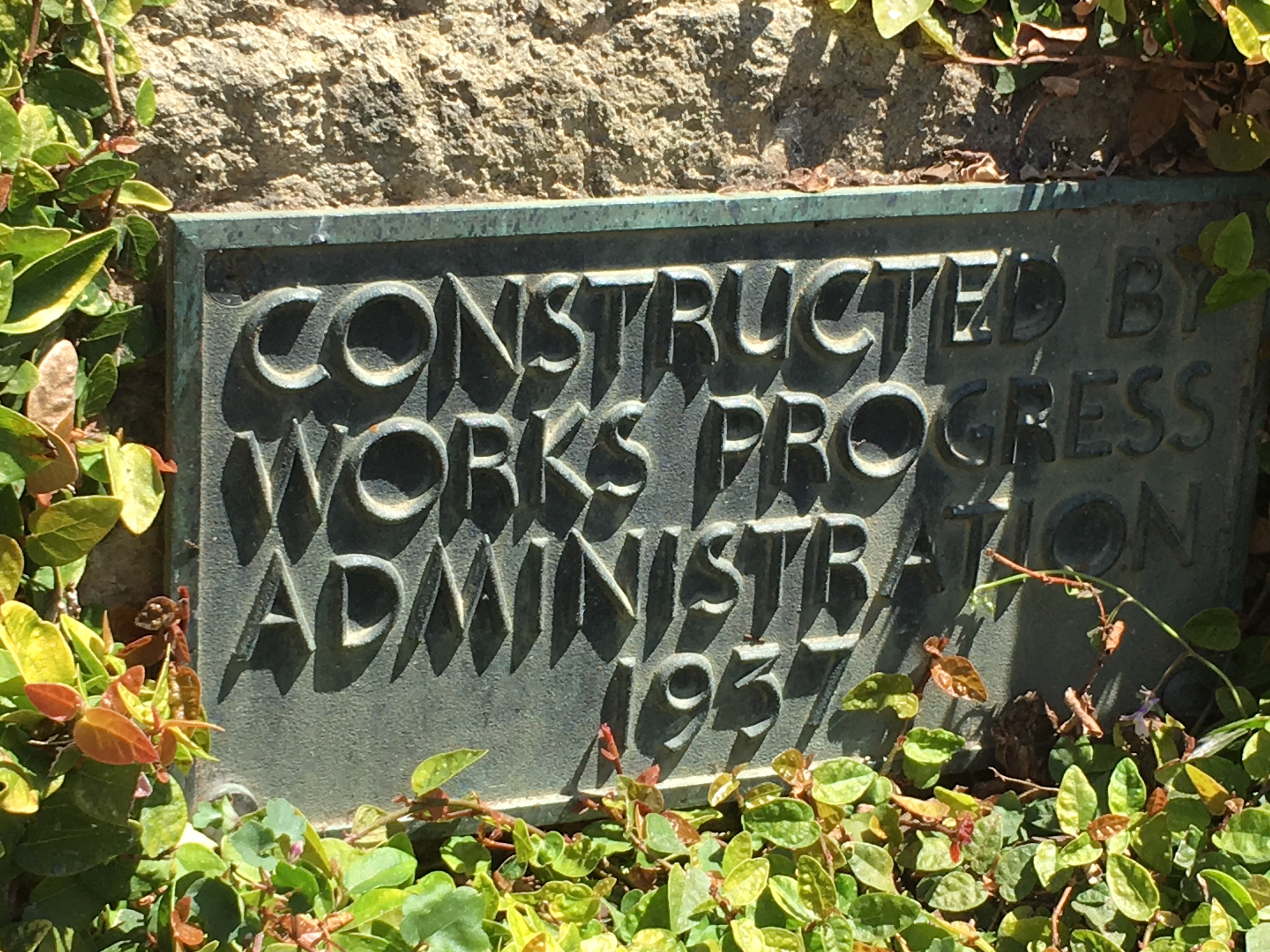

The result was the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which under Hopkins’ leadership provided millions of subsidized jobs over its seven-year run. The WPA ranks among the New Deal’s most successful programs. It might have lasted longer but for the nation’s shift to a wartime economy.

The New Deal’s history holds valuable lessons for the new Administration. “People don’t eat in the long run,” Hopkins said, “they eat every day.” The most powerful antidote to poverty is immediate employment and decent wages. With adequate earnings, most Americans can keep food in the refrigerator, avoid eviction or foreclosure and meet life’s other necessities.

So, here’s the deal, Mr. President. Just as FDR’s New Deal rested firmly on jobs programs like the CWA and WPA, your program to Build Back Better requires a large, permanent federal jobs program that will quickly put millions of Americans back to work—and by doing so, restore not only our economy but our faith in government as well.