Birds of the World

A New York City WPA Federal Writers’ Project book.

Photo Credit: Courtesy, Library of Congress

I’ve been writing a lot about the New Deal’s Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) lately: articles, a play of sorts, more than a thousand emails to politicians, editors and various keepers of the New Deal flame. Miraculously, after all this badgering, the office of Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance) has now drafted a bill to reinvent the Project.

Hundreds of millions of Americans today have no idea that anything like the federally funded Writers’ Project even existed. From 1935 to 1943 the FWP produced well-written, still-delightful guide books to 48 states, most major cities and U.S. territories. It also recorded oral histories of Americans from coast to coast—including Zora Neale Hurston’s groundbreaking interviews with formerly enslaved people. Writers as diverse as John Cheever, Ralph Ellison, Saul Bellow and Richard Wright got their starts on the Project.

Poster for Federal Writers' Project

Advertising “American Guide Series” volume on Illinois.

Photo Credit: Courtesy, Library of Congress

I’ve been buttonholing people and rhapsodizing about the FWP for almost a year now. I can make the case for a reinvented FWP til I’m blue in the face, but I’m really only trying to convince to convince 536 people—federal legislators to pass the bill, and President Biden to sign it. Some of those marks will be pushovers. The rest could be murder.

Plainly, these people may or may not care what I write in a national publication. But they damn well care about what their constituents think of them. They have to if they want to keep their jobs. Which is where, I hope, you come in. If you’re game, I ask you to write a letter or email on behalf of a reinvented Federal Writers’ Project to your member of Congress and/or senator. If you’re feeling frisky, throw in a local or statewide news outlet, too.

This is asking a lot, I know. These days, somehow, we’ve all got so much unstructured time that it feels like we have none at all. But believe me, coming from you, letters like these will be read, and they will count.

I’ll even give you some free ammo. The librarians of Rowan University in Glassboro, New Jersey, heaven bless them, have aggregated this list of links. to online versions of all but a few of the original WPA Guides.

American Guide Week

WPA Writers’ Projects describe America to Americans.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Library of Congress

If you haven’t spent much time with the American Guide to your own state or city, I urge you to dive in. While you’re at it, flag a passage or two that you think the readers of your letters might appreciate. And if ransacking the entire 700-page California Guide, for example, strikes you as daunting, by all means consult this indispensable treasury of good WPA writing culled from all the state guides. However you do it, when you write your letters, quote from a passage or two from an original guide. This will help to make the original FWP come alive on a regional level for people who don’t know the first thing about it—and if you feel like it, by all means loop me in.

If you know the city or town where your recipient lives, you might consider including a relevant passage as a grace note. If you’re writing to a member of Congress, you might cite an especially lyrical or wry description or passage about their district. If you’re writing to a newspaper editor, maybe send an anecdote about some crusading frontier journalist in their vicinity who got themselves horsewhipped for their trouble.

For instance, check out this nugget from the California Guide:

“Sebastian Vizcaíno, merchant-explorer, sailing into the bay in 1602, named it Monterey … and described it in such superlatives that those who came after him could not recognize it for 167 years.”

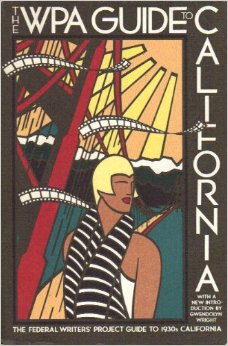

American Guide Series

WPA guide to the Golden State, history and culture, tours and trails, recreational facilities.

Photo Credit: Courtesy, Library of Congress

Authorship of the guide was maddeningly anonymous, but that line could well have come from the California poet Kenneth Rexroth or the feminist writer Tillie Olsen, who worked in the FWP’s California office. Whoever wrote it, Congressman Jimmy Panetta (D-Carmel) would probably get a big kick out of it.

Regardless of your state or the WPA guide you quote, make sure your reader understands that a new Federal Writers’ Project would be—like the original—a job-creation initiative. It would provide good, well-paying hard work for idle college graduates and laid-off workers (some of them journalists—but you can leave that part out.)

During its nearly eight-year run, the original FWP provided jobs for about 700 professional writers, editors and—not the least important job description nowadays—fact-checkers. In addition to the professionals, the original FWP also employed about six thousand destitute men and women who could, maybe, put a sentence together, but had zero related work experience when hired.

And yet, beyond its social and economic benefits, the most important goal of reviving the Federal Writers’ Project right now may be to help reintroduce a divided country to itself.

You’ll be urging your readers to create a candid, empathetic modern equivalent to the original guides—written and edited by some of their own constituents and drawing on interviews with their neighbors. If it helps, picture your senator or member of Congress handing out these guides to office visitors like cigars. (If the eventual published guides provide too candid a picture of your region, by then it will be too late).

Untitled, possibly Main Street of Twin Falls, Idaho

According to the Idaho State Guide, this town had the unusual distinction of being planned.

Photo Credit: Courtesy, Library of Congress

The New Deal is alive and the Living New Deal proves it. The Federal Writers’ Project lives on, too—in the American Guides, in the works of the great writers it launched and sustained, and in its priceless oral histories—an art form that the Project more or less invented.

Co-religionists, it’s up to each of us to demand the resurrection of the Federal Writers’ Project. If America needed it then, we sure as hell need it now.

You can find your member of Congress at https://www.house.gov/representatives/find-your-representative. You can find your senator at https://www.senate.gov/senators/senators-contact.htm. You can find your local opinion editor at their newspaper or radio station’s website. But hurry. The news desert you irrigate may be your own.