CCC and WPA artist Frank Cassara

A portrait of the artist in his studio.

Photo Credit: ©Kathleen Duxbury 2010 All Rights Reserved

Frank Cassara, a former Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and WPA artist died on January 13 at home in Ann Arbor, Michigan, two months shy of his 104th birthday. Frank’s persistence and talent earned him a place in New Deal art history. He was the last of the New Deal CCC artists.

During a 2010 interview, 97-year-old Frank and I reviewed government records detailing his enrollment as an artist in the CCC seven decades earlier, at Camp Swallow Cliff, Co. #1675-V, near Palos Park, Illinois. As Frank slowly read through the papers he looked up and said “I am starting to remember,”

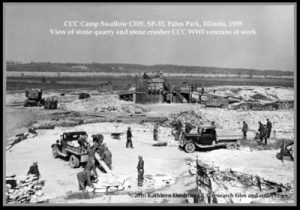

Enrollees from Camp Swallow Cliff, Palos Park, IL, 1935.

CCC men working in a limestone quarry. A stone crusher is in the background.

In 1934, living in Detroit and desperate for work, Frank sent a letter to the head of the Section of Painting and Sculpture at the U.S. Treasury Department, Edward Rowan, asking about a job:

Dear Sir, It has come to my notice that the government intends to send one hundred artists to C.C.C. camps. I am greatly interested in recording camp life and would appreciate any opportunity you could give me…. Thanking you for any information you can send me, I am, yours sincerely,

Frank Cassara

My meeting with Frank turned into two afternoons of unhurried memories—vignettes of a naïve young man, out of his element; vivid descriptions of CCC work projects, the cutting and crushing of stone at a local quarry, numbers painted on the side of a truck, and life in the barracks.

Frank brought his observations to life in the oil, watercolor, and pencil drawings he made during his yearlong CCC assignment. Exempted from heavy labor, artist/enrollees spent 40 hours a week depicting life in the camps. Their artworks were shipped to the Section of Painting and Sculpture Treasury Department in Washington, D.C.

After his discharge from the CCC, Frank again found himself without a job. By then, his work was known and admired by Ed Rowan and others at the Treasury Department, and in 1937 Frank was hired by the WPA’s Federal Art Project (FAP). He several murals in Michigan, at the Thompson School in Highland Park, a water plant in Lansing, and at post offices in Detroit and Sandusky, Michigan, eventually becoming a supervisor of the FAP for the state.

During World War II, Frank served as an artist with the Army Branch of Engineers in the American and Asiatic Pacific Theater. At war’s end, he became a professor of art at the University of Michigan, where he taught for 36 years.

Frank lived to the fine old age of 103 years and 10 months. He was drawing to the end of his life. Time spent with Frank Cassara remains a highlight of my CCC Art Projects research.