Rupert Lopez is 100 years old. He joined the CCC when he was about 18, serving from 1935 until 1940. As a CCC applicant Rupert had to pass a physical exam to show that he possessed three natural masticating teeth and was at least five feet tall and 107 pounds. Rupert said he had to eat a lot of bananas to make the weight requirement. New Mexico enrollees gained an average of 20 pounds in the CCC.

Enrollees could take a variety of evening classes while serving in the CCC. Rupert learned English from a teacher in Camp SCS-8-N, Catron Ranch in San Ysidro, New Mexico. In 1937 the CCC sent Rupert to college in Las Cruces. He later returned to the CCC as a Local Experienced Man. So-called “LEMs” lived in local communities and served as foremen overseeing less trained CCC workers.

Roster of men in CCC camp SCS-8-N in San Ysidro.

Rupert Lopez in the fourth man from the right in the front row. From Civilian Conservation Corps Official Annual 1936, Albuquerque District, 8th Corps Area, page 46.Photo Courtesy Dirk Van Hart

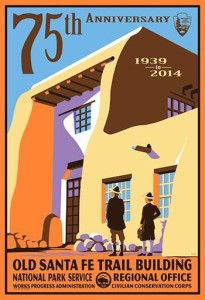

Rupert taught and supervised the production of adobe bricks used to build the Old Santa Fe Trail Building, a National Historic Landmark. The outstanding Spanish revival-style building served as the headquarters for the National Park Service Southwest Region for 56 years, from 1939 until 1995. Rupert is the last living member of the CCC who worked on the building, In 1940 Rupert moved to Corrales where he lives today.

On June 24, 2016, Rupert attended a ceremony in Santa Fe where he received the Kathy Flynn Award for his service during the New Deal.

The following was excerpted from an interview conducted by Deborah and Jon Lawrence at his house on Rupert’s Lane in Corrales, New Mexico, on July 11, 2015.

When I went to the CCC in 1935, I had just finished high school. I was about 18.

At that time I was working for 75 cents a day. When I joined the CCC, they put us on a truck. They wouldn’t tell us where we were going. They went west, out to the other side of San Ysidro, to the Espiritu-Santo Grant. There was a camp right there. It’s up off old Highway 44. Now it belongs to the Indians. There still are adobe ruins there.

When we got to the camp, the buildings were up. They still needed sewer and electrical lines. We worked with picks and shovels. I did that for probably two weeks. In high school, I had tried to take bookkeeping and typing classes because I wanted to clerk. When the CCC found out that I had finished school, they made me a warehouseman. A warehouseman could get $36 (a month) just to hand out the tools and supplies to the workingmen. Then the superintendent put me to typing and taking care of all of the books for the mileage in the trucks, the tools, the supplies, and so on. I took care of that.

The big wheels (at camp) were army captains and lieutenants. But the foremen, they were working people.

When we first went into Camp 8, there were already some people from Texas there.

We called them Tejanos. We had some problems with them. They didn’t like us. At meals, the tables were long. We ate on one side of the table; they were on the other side. They wouldn’t pass us anything. So we began to fight in the mess hall—Tejanos against the Spanish. Finally the commander stopped the fighting. He said, “If you want to fight, I am going to give you some gloves.” And he did. We didn’t fight with fists anymore, just gloves. We had good fighters, good boxers. They learned that our boys were better fighters than theirs. Little by little, all of the Texans went “over the hill.” (They deserted).

When I was working as a clerk at the camp, they started giving grants for college. They wanted me, so I went to college in Las Cruces. I thought it would get me all the way through college, but it only lasted for six months. There were only two men from the whole group who had enough money to finish school.

I worked on farms and I worked awhile at motorcycle delivery. I had an Indian 1932. Later, I traded my motorcycle for a 1932 Chevy.

Camp 8, with all the people, was transferred to Santa Fe. When I went back into the CCC, I was a Local Experienced Man. For Local Experienced Men, they chose men who could do something special, like making adobe. That was the only way that I could go in the CCC again. I was a leader. I was in charge. There were only two Spanish foremen, the others were all Anglos. They assigned me to teach the men how to make adobes for that big (NPS) building in Santa Fe. We made probably 500 adobes a day. It was hard work. It was a big project.

Rupert Lopez on his tractor

Lopez farmed 11 acres at his home in Corrales, NM. He also had an orchard of 400 peach and apple trees.Photo Courtesy Dirk Van Hart

I was married October 1939 during my tenure in the CCC. I met Reymunda in downtown Albuquerque at the skating rink. We used to skate together. We rented a house in Santa Fe—five dollars a month. We lived in Agua Fria, on the south side of that spring. Agua Fria was a spring that came in from the mountains. I used to travel on the motorcycle in the morning to be there at the CCC. I was a sargeant.

There was a time after I got married when I would go to school at night and take classes in English. Then I passed my examination for civil service and I got out. The CCC was being ended and they were closing a lot of camps. I got my discharge from the CCC in 1941. I went to work for Kirtland Air Force Base as a warehouseman. Then I transferred as an inspector to the National Guard. When I was in the National Guard, I was one of the guys who were appointed as an inspector to work in Korea. My wife stayed here. I was there for 18 months on active duty. Then I retired from the military.

When I came to Corrales they right away made me mayor domo of the church. At a meeting, we decided that our church was too old and it was cracking. Too much money was needed to make repairs. Since I was the chairman, Father Baca told me to make a drawing of a new church. So I drew a schematic of the church that I wanted. We held a fiesta and we collected enough money to make the new church. I was involved with the Planning and Zoning commission for 7 years, and I was on the Corrales Bosque Advisory Commission, and the Sandoval County Senior Affairs Board for 19 years and with the local Soil Conservation Service.

Then I used to farm. Chiles, tomatoes–you name it, I used to sell it. I would drive my produce as far as Grants and Manzano. I drove a tractor up until I was 98. I just stopped driving it two years ago. Now my son does the farming.