During the Great Depression, the New Deal brought jobs, hope, and progress to America. Libraries, courthouses, airports, schools, bridges, roads, trails, and public art are part of a vast New Deal legacy America still relies on but rarely recognizes. Through our growing open source database, The Living New Deal is making visible that enduring legacy. Our website shows not only the impact of the New Deal but also what can be achieved when our country rallies to serve the needs of ordinary Americans in hard times.

- Home

- /

- News, Articles & Newsletters /

- The Fireside

- /

- Spring 2012

Spring 2012

New Deal Art Disappearing from the Public Sphere

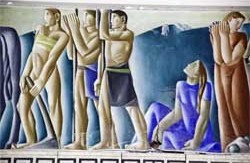

New Deal art is endangered as post offices are sold off, public buildings shuttered, and artworks are relegated to museum vaults and private collections. The New York Times reports that the University of California misplaced, then sold a 22-foot-wide carving by renowned African-American artist Sargent Johnson. The work, created under the Federal Arts Project, was valued at more $1 million. UC mistakenly sold it for $150. The Living New Deal and the National New Deal Preservation Association are working together to defend the New Deal’s legacy. We’re calling on UC to inventory its New Deal artwork, ensure its safekeeping, and publicly display another Johnson work that is currently in a locked conference room on the Berkeley campus. We’re also investigating the legal ruling the General Services Administration cited when it gave UC permission for the sale, and exploring how the Johnson carving can be returned to the public trust.

Take Action:

Contact: Robert J. Birgeneau, Office of the Chancellor UC Berkeley

200 California Hall #1500, Berkeley, CA 94720 (510) 642-7464.

Dismantling the Post Office

The liquidation of our commonwealth continues to gather steam. Several months after I published an article focusing on the sale of the downtown post office in Modesto, California, I learned that my own post office might soon be on the market.

Nearly a century old, the Architect of the Treasury Department modeled the downtown Berkeley Post Office on the Brunneleschi’s Renaissance orphanage in Florence, Italy, giving this university town one of the handsomest federal facilities in California.

Though, like the Modesto post office, Berkeley’s post office is not a New Deal structure, it contains two works of art from the New Deal period: a mural of Berkeley’s past by Suzanne Scheuer, and a sculptural relief by David Slivka.

There is no question that the U.S. Postal Service is in a state of crisis although many observers believe that crisis is more manufactured by those opposed to any government services than by competition from the Internet or private carriers. There can be no doubt, however, that many of the thousands of post offices scheduled for sale, closure, and possibly demolition sit on valuable real estate. Over 1100 of those facilities were built during the New Deal. They are often the finest buildings in many small towns, stately representatives of the federal government. Many contain sculpture, murals, and customized furniture whose fate is uncertain as the flags are lowered and post offices are thrown on the market.

U.S. post offices serve as vital gathering places and stimulants for downtown businesses that stand to be eliminated as post offices move to suburban shopping malls and are automated. Protests have been held as post offices have closed in Ukiah, Venice, and La Jolla., California. All contain New Deal art.

Opposition is growing to the progressive liquidation of the U.S. Postal Service and to the selloff of the buildings and art that were paid for and continue to serve the American public. New York University professor Steve Hutkins has devoted himself to stopping the privatization of this public resource, creating an invaluable website carrying information about community efforts around the country to save threatened post offices, as well as critiques of the ostensible crisis.

Rather than providing fewer services, for example, some suggest that the USPS could save itself and its invaluable assets by providing more services— specifically by reviving the postal savings bank that Americans once had and many other nations still enjoy.

One of the postal workers on the sculptural relief in the Berkeley post office’s loggia holds up a letter on which David Slivka carved a barely visible inscription. The return address is “All Mankind;” the recipient “Truth Abode on Freedom Road.”

Slivka was, I believe, making a statement about the vital role played by this trusted government service that facilitates communication among all its citizens. We must care for those abodes, for they belong to those of us traveling freedom’s road.

Gray Brechin is Project Scholar for The Living New Deal.

UPDATE: In a letter to a Senate panel that oversees the Postal Service, Sen. Bernie Sanders and 26 other senators suggested specific measures to stop wholesale closings of rural post offices and mail processing centers, and spare many of the 220,000 jobs that the Postal Service wants to cut.

Jobs Crisis Shows Need for ‘New’ New Deal

The nation is now experiencing the most severe jobs crisis since the Great Depression. President Barack Obama’s jobs plan will provide a much-needed extension of unemployment benefits and a payroll tax cut for working Americans. Nevertheless, only a federally funded jobs program, such as the Works Progress Administration, launched by President Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s, can fully address the catastrophe.

The official unemployment rate in September was 9.1 percent, and the U.S. Department of Labor reports that the actual unemployment rate was 16.5 percent, if you count part-time workers who want full-time jobs and workers who have simply stopped looking.

The long-term unemployed, or those unemployed for more than six months, now make up a postwar record 45 percent of the unemployed.

What did Roosevelt do that Obama is not doing? In the winter of 1933, with unemployment reaching 25 percent, Roosevelt established the Civilian Works Administration, a temporary jobs program that by early 1934 put 4.2 million unemployed workers to work repairing and building schools, roads, sewer lines and playgrounds. Simultaneously, Roosevelt started the Public Works Administration, which funded long-term infrastructure projects such as highways, bridges, dams and public buildings.

In 1935, the administration launched the Works Progress Administration, which employed 6 million over the rest of the decade constructing public works projects such as highways, schools, parks and airports and operating arts, educational and media programs. By 1936, production doubled, the unemployment rate dropped by half, and the recovery began.

To tackle our current unemployment crisis, the federal government should spend $500 billion a year over the next three years on an emergency jobs program. The first step is to create immediate full-time jobs for the unemployed — at the median wage of $16.27 an hour — in human services (e.g., child care, health care, home care) and energy conservation (e.g., retrofitting homes and public buildings).

To this should be added a public works program to build schools, bridges, a “smart” electrical grid, zero emission buses, high-speed rail, wind farms and affordable housing.

Finally, federal assistance to the states is needed to reverse cutbacks of vital public services and public employment. The loss of 600,000 teaching, public safety, transit and other government jobs over the past three years has contributed measurably to the downturn.

How to pay for such a jobs program? First, the government can continue to run temporary deficits that are now relatively high at 10 percent of GDP in 2010 but still dramatically lower than the 30 percent of GDP peak during World War II. The key is public investment to create jobs for the unemployed, fund public works, rehire public employees and put money in the hands of ordinary people to bolster demand.

Second, we must heed investor Warren Buffett’s call to “stop coddling the rich” and raise taxes on the wealthy and close corporate loopholes.

The upper 1 percent’s share of income reported for tax purposes increased from 9 percent in 1976 to 24 percent in 2007, according to UC Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez. Nearly half of total income went to the upper 10 percent in 2007 compared to 33 percent 30 years earlier. The top income tax rate on the highest income earners was 70 percent between 1940 and 1980. It is now just 35 percent.

Moreover, profits have reached post-World War II highs, exceeding 26 percent of corporate income in 2010. The Center for Tax Policy reports that federal revenue from corporate taxes has dropped by half over the past 60 years and corporations such as Verizon, Bank of America and General Electric pay essentially no taxes due to loopholes in the tax code.

Ending the Bush-era tax cuts for the upper 2 percent, set to expire in 2012, will generate more than $80 billion a year. A 0.5 percent transaction tax on the transfer of stocks and securities would yield $175 billion annually from the largest financial institutions and speculators. If corporate tax loopholes and subsidies are eliminated, federal tax revenue will increase by $365 billion a year.

Republicans oppose taxing the rich, just as they did in the 1930s. It will take popular mobilization by labor, faith, civil rights, women’s and youth organizations to overcome such resistance — just as it did then. Occupy Wall Street may be the beginning of a movement for a new New Deal. Collective action worked in the 1930s, and it could work again now.

Martin J. Bennett teaches American history at Santa Rosa Junior College and is co-chair of the Living Wage Coalition of Sonoma County. Richard A Walker is a professor of Geography at UC Berkeley and Research Director at The Living New Deal.

Woody Guthrie at 100

Oklahoma is now ready to accept and celebrate native son Woody Guthrie, the seminal American folk singer who died in 1967. The state resisted honoring Guthrie for decades because of his leftist politics. “I ain’t a Communist necessarily,” Guthrie said, “but I been in the red all my life.” Read more at nytimes.com

Oklahoma is now ready to accept and celebrate native son Woody Guthrie, the seminal American folk singer who died in 1967. The state resisted honoring Guthrie for decades because of his leftist politics. “I ain’t a Communist necessarily,” Guthrie said, “but I been in the red all my life.” Read more at nytimes.com

Remembering Stetson Kennedy

Author, folklorist, environmentalist, labor activist, and human rights advocate, Stetson Kennedy, died last year at age 94. During the Depression, Kennedy joined the WPA in Florida and worked for the Florida Writers Project. Kennedy published eight books, including “The Klan Unmasked.” It was one of the strongest blows to the Ku Klux Klan…Read More at nytimes.com

Hidden Murals Found in Rhode Island

New Deal murals by WPA artist Gino Conte were unveiled recently at the University of Rhode Island. Ironically, construction workers hired under the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act, a federal jobs program, rediscovered the murals, which had been hidden behind a wall since the 1960s…Read more at ramcigar.com