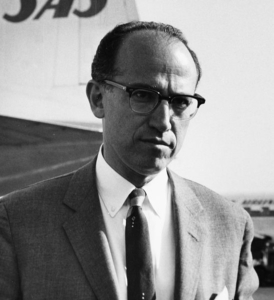

Dr. Jonas Salk

Courtesy, Wikipedia Commons.

Church bells rang. Loudspeakers in department stores shared the news. Factories paused production to spread the word to jubilant coworkers. Families huddled in their parlors around their radios for the latest updates. There was glee, relief, resounding joy across the country. It was March 3, 1953, the year Dr. Jonas Salk, a 40-year-old medical researcher, famously announced that he and his team at the University of Pittsburgh had successfully tested a vaccine that would end polio.

The Salk vaccine was readily accepted and celebrated, in part because of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s leadership. Roosevelt had a personal stake in eradicating polio. He had contracted the

FDR is aided exiting a car 1932

Photos of FDR’s disability from polio are rare. Courtesy, FDR Library, public domain.

disease in 1921 when he was 39 years old and would never walk again without leg braces or assistance. It spurred him to create the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. In 1938, entertainer Eddy Cantor used his radio show to enjoin people to donate a dime in honor of the president’s birthday. The White House received more than two and a half million dimes totaling $268,000. The foundation was later renamed the March of Dimes.

“Roosevelt’s passion for finding a solution—a cure, a vaccine—made polio a priority coming from the very top leader in the country, says Stacey Stewart, current CEO of the March of Dimes. “People across the country felt like they were called to duty. It was a call to action, like the war effort.”

Staged photo of polio patient and nurse. Courtesy, Polio Canada/Ontario March of Dimes.

The Mothers March, the first March of Dimes fundraising event, began in 1950. Armies of volunteers went door-to-door handing out information about polio and the efforts to stop it. Lapel pins were sold for ten cents each; special features were produced by the motion picture studios and radio industry; and nightclubs and cabarets held dances and contributed a portion of the proceeds.

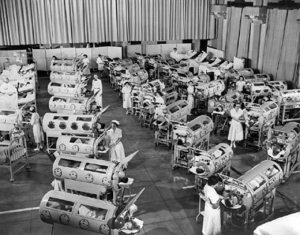

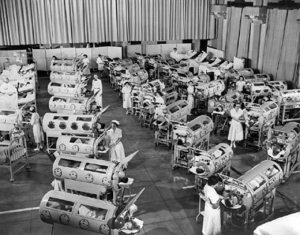

During the 1940s and 50s, according to statistics from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, polio disabled an average of 35,000 people a year in the United States alone, most of them children. Polio peaked in 1952 at 57,879 cases. 3,145 people died. Those that survived the polio virus would oftentimes be crippled for life, forced to use crutches, wheelchairs, or be placed into iron lungs in order to breathe.

Iron lungs in Los Angeles school gym. Courtesy, Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center.

Salk and his team at the University of Pittsburgh developed the poliomyelitis live vaccine. Leading up to the vaccine’s 1954 release, parents volunteered their offspring in clinical trials, including Salk, who inoculated his is own children as part of the study. By August 1955, some 4 million shots were given. By 1956, cases of polio in the United States had dropped to 5,876, one-tenth of its 1952 peak. The United States has been polio free since 1979. Today, 92.6 percent of children 2-years and younger have been vaccinated for polio.

FDR and March of Dime foundation director Basil O’Connor counting dimes, 1938. Courtesy, March of Dimes.

America is far from free of COVID. Misinformation and resistance to COVID vaccinations persist, putting many at risk. As of this writing, there have been nearly 53 million cases of COVID, and 820,000 related deaths, according to the CDC. 505 million doses of the various COVID vaccines have been dispensed. 204 million people have been fully vaccinated—only about 61.9 percent of the population.

A number leading experts, including former president Trump’s coronavirus testing tsar, Dr. Brett Giroir, have suggested that hundreds of thousands of deaths could have been avoided had there been clearer direction and action taken. More than 400,000 Americans died during Trump’s term. Church bells of a different kind.

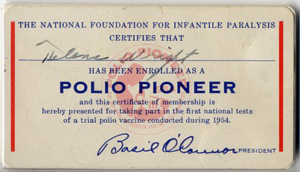

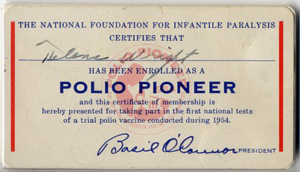

Polio Pioneer

The first mass trails of polio vaccine took place in 1954. Ultimately, more than a million elementary school children were enrolled in the trials, the largest public health experiment in history.

Because Franklin D. Roosevelt founded the March of Dimes, a redesign of the dime was chosen to honor him a year after his death. The Roosevelt dime was issued in 1946, on what would have been the president’s 64th birthday.

Dr. Salk received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Jimmy Carter in 1977. Canadian biochemist Ian MacLachlan created the innovative delivery system to get Moderna and Pfizer MRNA vaccines into one’s cells. No word on what medal he may receive, if any.

Jonathan Shipley is a freelance writer based in Atlanta, Georgia. He's written for such publications as the Los Angeles Times, National Parks Magazine, and Seattle Magazine.