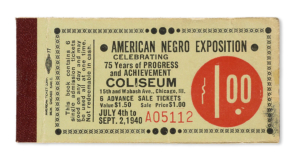

The WPA Federal Theatre Negro Unit presents Shakespeare’s “Macbeth”. Artist: Anthony Velonis. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

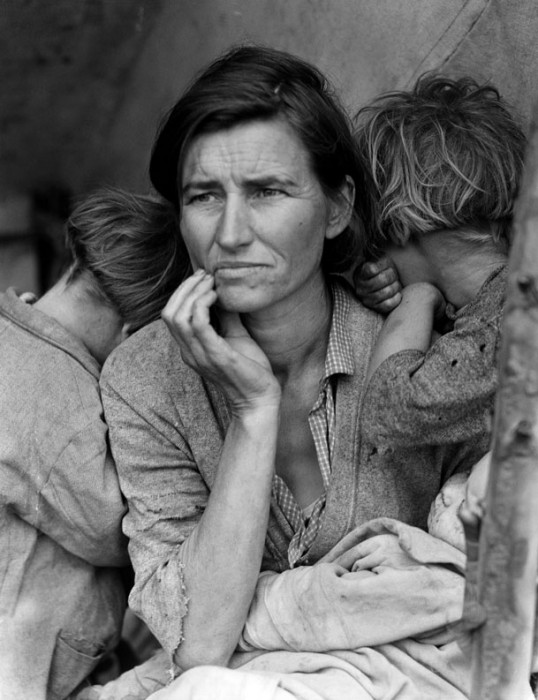

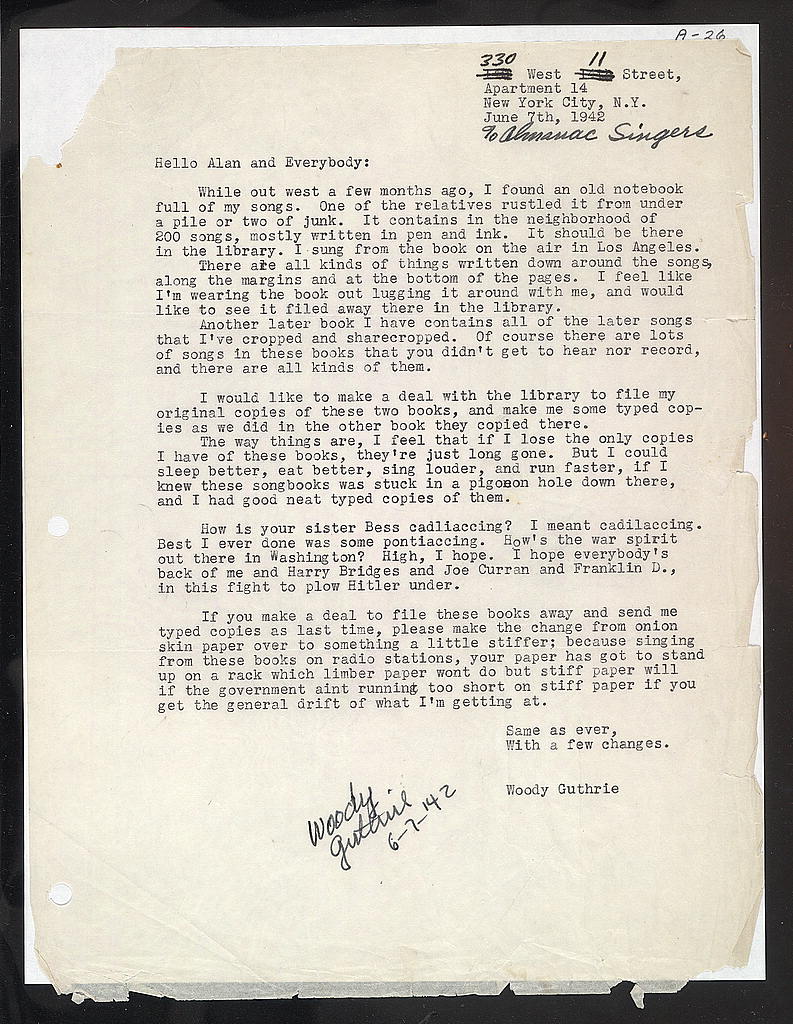

It was April 14,1936 and the nation was mired deep in the Great Depression. But joy could be found that night in Harlem at the Lafayette Theatre. It was the glitzy world premiere of the Federal Theatre Project’s Negro Theatre Unit production of Shakespeare’s MacBeth, directed by the 20-year-old Orson Welles.

Traffic was stopped for blocks. Audiences, abuzz with anticipation, crowded into the theater lobby wearing suits, ties and tipped fedoras; ball gowns, pearls and fur stoles.

“Voodoo MacBeth,” set at a fictional Caribbean island featuring an all-Black cast. “There was [sic] so many curtain calls that they finally left the curtain open,” Welles would recall. “When the play ended, the audience came up to the stage to congratulate the actors.” The show would be sold out for weeks. It was a smashing success and helped promote Black theatre and Black artists.

Created in 1935 as part of the New Deal’s economic recovery program, the WPA’s Federal Theatre Project (FTP), was the federal government’s most ambitious effort ever to organize and produce live theatre events. The FTP was not so much meant to provide cultural activities as it was to employ artists, writers, directors, actors and other theater workers.

There were 1,200 FTP production companies across the country, at one point employing some 12,700 people. Nine out of every ten of these workers came from the relief rolls.

Hallie Flanagan, national director of the Federal Theatre Project on CBS Radio for Federal Theater of the Air, 1936. Courtesy, Wikipedia.

The Negro Units, also called the Negro Theatre Project (NTP) had offices in 23 cities, including New York, Philadelphia, Hartford, Boston, Portland (Oregon), Los Angeles, Raleigh, and New Orleans. Hallie Flanagan, the FTP’s director, insisted on observing the WPA’s policy against racial discrimination, providing much-needed employment and apprenticeships to hundreds of black actors, directors, theatre technicians and playwrights.

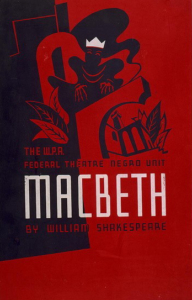

“Voodoo MacBeth” was the NTP’s most successful production. Many others were also well-received by critics and the public. The NTP performed classics by Shakespeare and Shaw as well as contemporary works, many focused on racial injustice, such as Frank Wilson’s drama Walk Together, Children, about the forced deportation of one hundred African American children from the South to the North to work menial jobs, and Go Down Moses, about the abolitionist Harriet Tubman.

Federal Theatre poster for George Bernard Shaw’s “Androcles and the Lion,” a production of the Negro Theatre Project. Artist: Richard Halls, Courtesy, Library of Congress.

The NTP also performed Arna Bontemps and Countee Cullen’s mystery, The Conjure Man Dies and The Swing Mikado, a jazz version of Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera.

Though it lasted only four years, the FTP played in some 200 theaters nationwide to 30 million people—many of them never having experienced live theater before.

Congress terminated the FTP in 1939 following a series of hearings by the House Committee on Un-American Activities and Subcommittee on Appropriations investigating the FTP’s leftist commentary on social and economic issues.

Propelled during the Great Depression, Black theater is thriving eight decades after “Voodoo MacBeth” opened in New York City. Many organizations nurture the Black performing arts, such as Pittsburgh’s August Wilson African American Cultural Center, Los Angeles’s Ebony Repertory Theatre; Houston’s Ensemble Theatre, National Black Theatre, Penumbra Theatre, Pyramid Theatre Company and Harlem Stage.

WPA Federal Theatre Negro Unit in “Noah,” a human comedy. Artist: Aida McKenzie. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

This year, the Atlanta-based True Colors Theatre Company, plans to host the Next Narrative Monologue Competition, in which high school students perform the works of contemporary Black playwrights. The finalists will appear at the fabled Apollo Theatre in Harlem, just a few blocks from where NTP actors had performed Shakespeare to the delight of audiences and themselves.