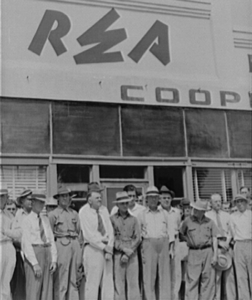

Rural Electrification

Members of the REA cooperative in Hayti, Missouri at an annual meeting. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

The New Deal’s legacy is everywhere, in ways both grand and modest. If you want to see the New Deal you don’t really need to know where to look: you just need to know what you’re looking at.

Our public spaces were, and still are, shaped by the New Deal. Almost anywhere in the United States you are probably near a post office, library, school, park, museum, bridge or sidewalk built or improved by the New Deal. So, it’s not surprising that the New Deal of infrastructure is probably the New Deal that first comes to mind.

But when I say that New Deal is everywhere, I really mean everywhere, especially in economic activity.

If you have a bank account, your deposits are insured by the New Deal’s Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, operating since 1933.

If you’ve used money to buy stocks, you’ve made use of the New Deal’s Securities and Exchange Commission, established in 1934 to enforce trading transparency laws.

Overseas Highway connecting mainland Florida to Key West

Built by the PWA, the 100-mile-long highway stretches over the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. Courtesy, State Library and Archives of Florida.

If you’ve bought a house, you’ve certainly made use of, at least indirectly, the Federal National Mortgage Association better known as Fannie Mae, created in 1938 to enable a national mortgage market.

But you don’t have to be carrying on high finance to feel the economic impact of the New Deal in your daily life.

If you’ve joined a union, you’ve made use of the New Deal’s Wagner Act of 1935, which protected the right to organize and bargain collectively.

If you’ve earned minimum wage, thank the New Deal’s Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which also barred child labor.

If you or someone in your family has drawn a federal old-age pension, disability benefits, or unemployment insurance, you’ve made use of the New Deal’s Social Security Act of 1935.

But even that summary underestimates the economic ubiquity of the New Deal:

The dollar we use today is a creation of the Roosevelt Administration’s first days in office, when the president took the dollar off the gold standard and secured from Congress the authority to change the value of the dollar to ensure the smooth functioning of the economy. If you’ve ever been paid, saved, spent or even handled a dollar, you’ve come into contact with the New Deal.

The New Deal shaped the land. Policies we still have today to control production and sustain use of the soil began with the Agricultural Adjustment Acts of the 1930s.

New Deal agencies, like the Tennessee Valley Authority, built dams to generate power for impoverished rural regions, transforming the kinds of industry that could take place there.

Developing National Parks

CCC crews leave for job sites in Grand Canyon National Park, 1934. Courtesy, Grand Canyon NP Museum Collection.

The original New Deal was—in its way and for its day—green. It introduced the idea of ecological thinking to large-scale policy. When we think about a Green New Deal, we should remember the innumerable trees, parks, trails and firebreaks installed by the Civilian Conservation Corps.

The New Deal also brought an end to the 19th-century policies of homesteading and allotment, which broke up federal and Native lands and parceled them out to individual owners. It restored control of Native lands to Native nations, which renewed recognition of their sovereignty.

Road-building programs—by far the largest part of the Works Progress Administration—knitted disparate parts of the nation together, making remote locales accessible for travel and commerce, thus making the postwar economic boom possible.

The Air Traffic Control system is a result of the New Deal, as is the Federal Communications Commission.

Workers at the Social Security Administration

The SSA used IBM tabulators to keep track of enrollees in the system. Courtesy, Wikimedia.

The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank and, indeed, the United Nations itself are institutions that carried New Deal programs and ideals into the postwar world.

To say the New Deal matters is to realize that it gave shape to our world and that we reckon with it every day. But its ubiquity is only one reason the New Deal still matters.

We remember the Great Depression as an economic crisis. But we should also remember that to Roosevelt and many who voted for him the Depression caused a crisis of democracy.

Americans went hungry as unemployment skyrocketed. Millions of Americans became refugees in their own country.

At least so far as FDR’s predecessor, Herbert Hoover was concerned, government could do little, or at any rate, would do little, to help. When Americans protested this inaction, the government proved it could rouse itself quite swiftly to send out the army to teargas protesters and run them off. Within the United States and around the world, many wondered if democracy had reached its end.

Roosevelt was, more than most people, sensible of this threat. Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933, just after FDR won election to the presidency. A friend told FDR if he succeeded he would be remembered as one of the greatest American presidents, and if he failed, he would be remembered as one of the worst. Roosevelt responded, “if I fail, I may well be the last.”

The New Deal was, and remains, imperfect. But it held out the promise and demonstrated the possibility of an improved democracy for Americans, which is why, even to those mindful of the New Deal’s shortcomings, the New Deal still matters very much today.