- Home

- /

- Racism and Beyond: A...

- /

- A New Deal For...

- /

- Women and the New...

Women and the New Deal

Scroll down for our photo gallery below!

Recalling the New Deal years, Molly Dewson, a high-ranking member of the Democratic Party during the time, said: “At last women had their foot inside the door. We had the opportunity to demonstrate our ability to see what was needed and to get the job done while working harmoniously with men. The opportunities given women by Roosevelt in the thirties changed our status” [1].

Though some women had served in leadership positions in the federal government before the Roosevelt Administration–for example, Grace Abbot and Katherine Lenroot of the U.S. Children’s Bureau–the New Deal swung the federal doors wide open. Frances Perkins became the U.S. Secretary of Labor and the first woman to be appointed to a cabinet-level position; Josephine Roche was appointed Assistant Secretary of the Treasury; Ellen Woodward became chief of the WPA’s Women’s and Professional Projects division; Mary McLeod Bethune became head of the Office of Minority Affairs at the National Youth Administration; Hallie Flanagan led the Federal Theatre Project; and Nellie Ross took charge of the U.S. Mint [2]. Eleanor Roosevelt, of course, was an extraordinary first lady, fierce defender of civil rights, and foremost women’s advocate of the time.

Many other women took important posts, or were promoted to leadership roles in promoting national recovery, administering relief programs, managing day-to-day operations of the government, and addressing the interests and needs of women, including Marion Glass Bannister (Treasury), Clara Beyer (Department of Labor), Jo Coffin (Government Printing Office), Jane Hoey (Social Security Administration), Lucy Howorth (Veterans Administration), Mary La Dame (U.S. Employment Service), Hilda Smith (WPA), Belle Shirwin (Advisory Council, Committee on Economic Security), and Helen Tamiris (Federal Theatre Project, Federal Dance Project) [3].

On November 20, 1933, many of these leaders gathered at the White House with Eleanor Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins to discuss work-relief projects for women. Hopkins told them: “I am committed to a belief, a conviction on my part, that it is possible to put three to four hundred thousand women to work on good projects and to do it very quickly…” This conviction, alongside the energy and various project ideas of the attendees, led to a great number of employment opportunities for jobless women over the next ten years [4]. For example, by February 1934 there were about 275,000 women working in the Civil Works Administration (CWA) [5] and by the following February, there were about 204,000 women in the Work Division of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration [6].

The WPA (1935-1943) brought even more work-relief opportunities for women, with numbers employed frequently exceeding 300,000 and peaking at 409,954 in September 1938 [7]. The National Youth Administration (NYA) was another source of meaningful work for women in need; in March 1940, about 235,000 young women were enrolled in the NYA’s student work program (high school, college, and graduate school) and 142,000 in the NYA’s out-of-school work program. This brought total New Deal work-relief for women to about 743,000 at that date [8].

Given the gender roles of the time and the New Deal’s emphasis on public works projects when construction was defined as a masculine occupation, the employment of women in work-relief programs rarely equaled the employment of men. The number of women with jobs in the WPA typically ranged from 13-18% of total WPA employment and there were no female enrollees at all in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). The NYA was a different story, with the number of women sometimes equaling or exceeding the number of men [9].

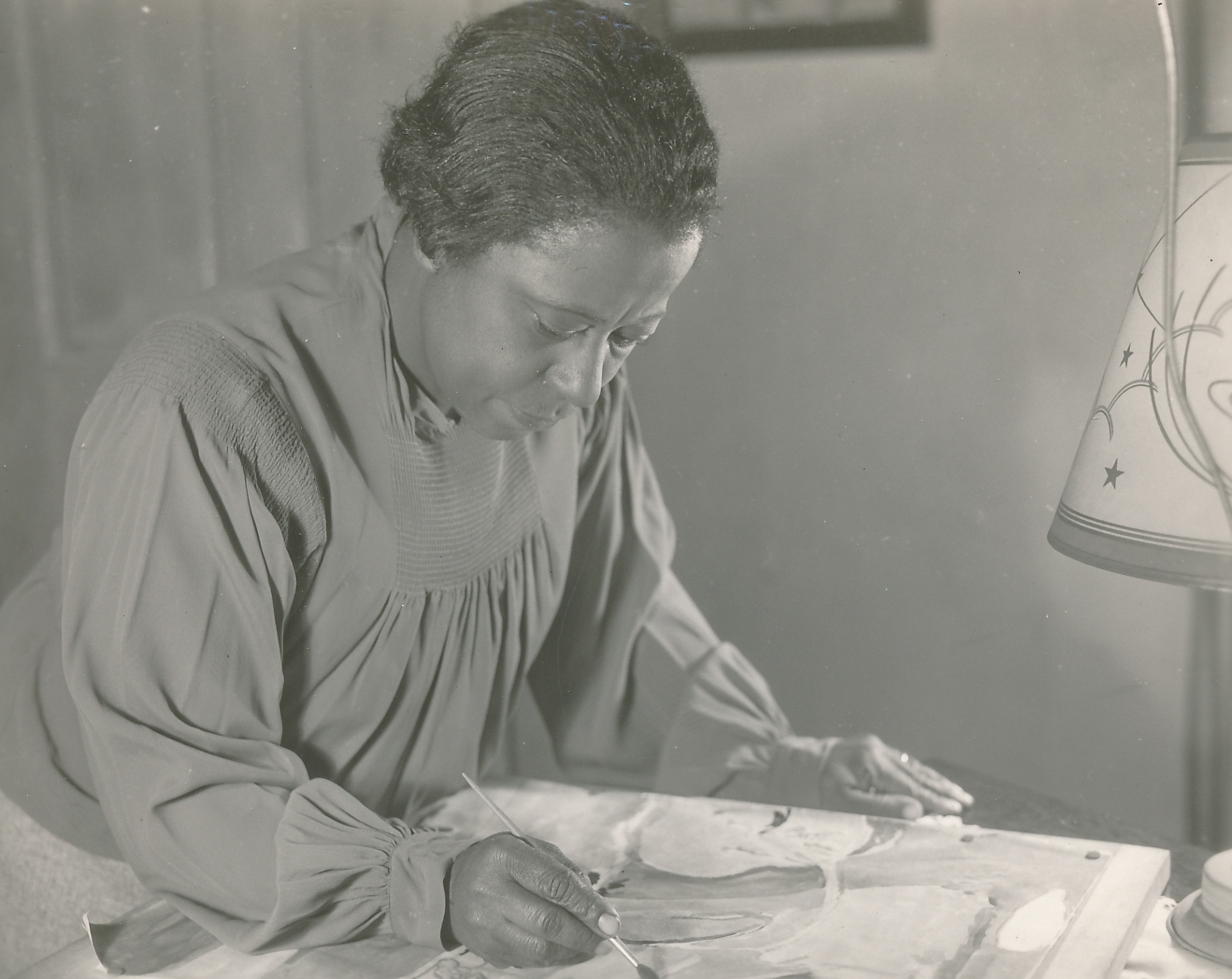

Irrespective of total employment numbers, the types of projects that women performed in the work-relief programs were just as varied and productive as the projects carried out by men – in some cases, more so. Sewing projects employed the greatest number of women, and these workers churned out half-a-billion articles of clothing, bedding, stuffed animal toys, and other items useful to low-income Americans. Women were largely responsible for the WPA’s school lunch program and they made and served over 1.2 billion nutritious meals. Women housekeeping aides made 32 million home visits to Americans who needed help [10]. WPA women were also involved in archaeology, historic preservation, scientific research, gardening, canning, toy repair, nursery schools, healthcare, furniture repair, libraries, teaching, recreational leadership, record organization, art, music, writing, acting, dancing, and much more.

Struggling women who were not hired into work-relief programs still found assistance in New Deal programs, such as food and goods distributed through the Federal Surplus Commodities Corporation and the Food Stamp program. Families received the bulk of pay going to their sons in the CCC (a government requirement) and women and children participated in large numbers in the WPA’s popular recreation and education programs.

The New Deal was a revolutionary era, opening up a vast new space of opportunity and benefits for women, one that tapped into their leadership abilities, wide-ranging skill sets, and life experiences like never before.

Sources: (1) Susan Ware, Partner and I: Molly Dewson, Feminism, and New Deal Politics, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987, p. 193. (2) Susan Ware, Beyond Suffrage: Women in the New Deal, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981, pp. 142-155. (3) Ibid., and also see “CES Report,” Social Security Administration (accessed March 23, 2018), as well as some biographies at “New Dealers,” Living New Deal. (4) See note 2, pp. 106-107. (5) Henry G. Alsberg, America Fights the Depression: A Photographic Record of the Civil Works Administration, New York: Coward-McCann, 1934, p. 115. (6) Federal Emergency Relief Administration, The Emergency Work Relief Program of the F.E.R.A., April 1, 1934 – July 1, 1935, 1936, pp. 119-121. (7) Federal Works Agency, Final Report on the WPA Program, 1935-43, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946, p. 44. (8) Ibid., and also see Federal Security Administration, War Manpower Commission, Final Report of the National Youth Administration, Fiscal Years 1936-1943, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1944, pp. 55, 245, and 253. (9) See the previous two notes. (10) See note 7, p. 134.