The “Blue Bible,” compiled 82 years ago, is a “best of” the PWA’s thousands of construction projects. Photo by Gray Brechin.

President Biden’s initial $2.3 trillion infrastructure proposal is merely a belated down payment on decades of cost-cutting neglect and deferred maintenance that has brought much of U.S. infrastructure to near third world status. If it passes Congress, his proposal would create a myriad of needed jobs, but it’s also a reminder of the stupendous feat that ”Honest Harold” Ickes achieved modernizing the country in just half a decade. During that time, he served as both a seemingly never sleeping Secretary of the Interior and head of the Public Works Administration (PWA), a vast public works construction agency often confused with its sometimes rival, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) under Harry Hopkins.

Harold Ickes

As U.S. Secretary of the Interior throughout FDR’s presidency, Harold Ickes was in charge of implementing major New Deal relief programs, including the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the federal government’s environmental efforts. Courtesy, Wikipedia.

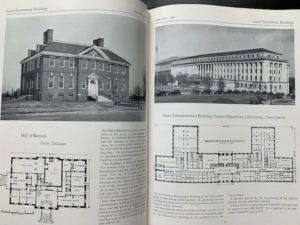

I call the doorstopper of a tome with the snoozer title Public Buildings: Architecture Under the Public Works Administration, 1935-1939 the Blue Bible not only for its buckram binding of that color but also because of the volume of information, much of which the Living New Deal has used on its website. Published by the Government Printing Office in 1939, the richly illustrated book is proof of what could be accomplished in the future.

Contracting with both small, local and giant construction companies such as Bechtel and Kaiser, the PWA stimulated the economy by building dams, airports, schools, colleges, bridges, public hospitals, art galleries, sewage treatment plants, lighthouses, libraries and even sleek Staten Island ferries and Coast Guard cutters. At over 600 pages of text, black and white plates and floor plans arranged by building type, the book shows a nation transformed in short order, yet it is only an abbreviation of a larger report requested by President Roosevelt and compiled by architects C.W. Short and R. Stanley-Brown. They culled hundreds of what they regarded as all-stars from more than 26,000 PWA projects, many of which remain to be discovered.

Blue Bible Project page

The PWA funded and administered the construction of more than 34,000 projects. Many outstanding examples appear in these pages. Photo by Gray Brechin.

Despite the gigantic scale and quality of many of the buildings, the plates included in the book identify neither the architects nor engineers responsible for the projects, although the cost is given. They show the smorgasbord of styles popular during the New Deal, ranging from Georgian to Pueblo, from Art Deco and Streamline Moderne to hints of the new International Style. Lavish government patronage led many artists employed by New Deal agencies to compare their era to that of the Renaissance. The architects who compiled the book wrote, “Today architecture in the U.S. is passing through a period of transition, thus creating a condition which has much in common with that which existed in Italy in the 15th century when the architecture of the Middle Ages was changing to that of the Renaissance.”

Bonner's Ferry Bridge, Spanning Kootenai River, Idaho

The PWA’s accomplishments include building LaGuardia Airport, the Tri-borough Bridge, and Lincoln Tunnel in New York City; the Skyline Drive in Virginia, and the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge and the Grand Coulee Dam. Courtesy, Bridgehunter.com

Scanning the book reminds me of architect and urban designer Daniel Burnham’s famous command in the early 20th century: “Make no small plans,” he said, since “they have no magic to stir men’s blood.” Ickes himself said when dedicating California’s Friant Dam that “Even those of us in Washington who are responsible for carrying out orders sometimes lack comprehension of the mighty sweep of this program.”

Short and Stanley-Brown closed their introduction with a claim you won’t find in any government report today: “This vast building program presents us with a great vision, that of man building primarily for love of and to fulfill the needs of his fellowmen. Perhaps future generations will classify these years as one of the epoch-making periods of advancement in the civilization not only of our own country, but also of the human race.”

PWA Map

Vintage poster describing some of the PWA’s construction projects across America. Courtesy, Digital.library.Cornell.edu

The Blue Bible reminds us today how far the U.S. once materially advanced civilization, even as forces in Europe conspired toward its destruction.

Copies of the book can be acquired on Amazon as originals or as a 1986 paperback reprint by Da Capo Press.