The City Auditorium has served as Colorado Springs favored venue for public events since 1923. In the past, circuses, dance, and music reigned in the Classical Revival building. In recent years it has played host to cat shows, wrestling, and psychic fairs.

In 1934, under the Public Works of Art (PWAP) section of FDR’s New Deal, Boardman Robinson, the Southwest Coordinator of New Deal Art, and city officials selected two artists to paint lunette murals in the auditorium’s foyer. Both murals were to represent the focus and purpose of the public building.

Both artists were members of the Broadmoor Art Academy, an early oasis of art and culture in Colorado Springs. It was academy instructor George Biddle who wrote to his former classmate at Groton, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, proposing a program for artist relief. Many of the academy’s instructors and students were soon hired under New Deal art programs to paint murals.

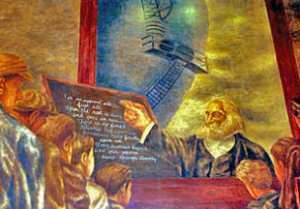

The Arts Mural by Tabor Utley

One of two recently conserved murals in the City Auditorium in Colorado Springs.

Tabor Utley taught landscape painting at the academy. His lunette at City Auditorium depicts the performing arts—dance, theatre, orchestral music, and a gospel choir. Facing it is a lunette painted by Utley’s student, Missourian Archie Musick. “Hard Rock Miners,” is Musick’s first major mural. It depicts the history of the area—gold mining and the cultural environment that the industry supported. Musick went on to paint New Deal murals at post offices in Red Cloud, Nebraska and Manitou Springs, Colorado.

When City Auditorium was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992, the murals were in bad shape, suffering from cracks in the plaster, moisture in the walls, and layers of accumulated smoke and grime.

Unfortunately, conservation was a low priority given the City’s budget and there was confusion about who was responsible for the care of the murals.

In 1998, Archie’s daughter, artist Pat Musick, and I decided to take on the conservation project ourselves. The then-director of the building became our third mover and shaker.

Hardrock Miners by Archie Musick

One of two recently conserved murals in the City Auditorium in Colorado Springs.

Through much networking, fundraising, and lobbying, we were on our way to getting the City to be our partner. Our efforts led to a grassroots campaign, “A New Deal for the New Deal of Southern Colorado.” The Pikes Peak Arts Council became our fiscal sponsor, which enabled us to apply for grants not available to the City. We managed to secure funding from two local organizations, The El Pomar Foundation and the Gay and Lesbian Fund for Colorado.

We raised $10,000, which the City matched, to hire a local conservator. A lab analysis confirmed that both murals were painted in oil. Conservation began in early 2004 to stabilize, consolidate, and clean them. The restoration included new lighting and a Data Logger to monitor environmental conditions.

We held a public unveiling of the newly conserved murals, and received an award from the Arts, Business, and Education Consortium. We were invited to the annual Saving Places conference in Denver, hosted by Colorado Preservation, Inc, and were surprised to find our project on the cover of the conference issue of their magazine.