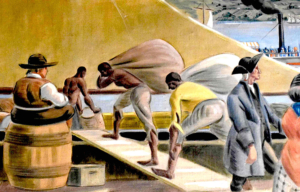

Mural, Life of Washington, by Victor Arnautoff, 1937

New Deal artworks often contain social criticism, leading to controversies over censorship. Courtesy, George Washington High School Alumni Association.

New Deal art programs ushered in a watershed decade for American art. From 1933 to 1943, federal art programs hired tens of thousands of unemployed artists, producing over 200,000 artworks, and temporarily making the federal government the single largest patron of contemporary art in the world.

This unprecedented and visionary patronage diversified who made American art and who had access to it, resulting in an immense and widely dispersed New Deal art collection owned by the American people. However, federal funds to properly document, store and preserve New Deal art were not forthcoming, leaving much of

Redwood Screen, by Sargent Claude Johnson

Johnson, an African American artist, worked for the WPA and was a major art figure in the San Francisco Bay Area. His carved redwood screen, commissioned under the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), was once part of UC Berkeley’s art collection, but was neglected and relegated to storage. In 2009, it was sold as “surplus” to a private buyer for $164.63. The work was ultimately acquired by The Huntington. Courtesy, The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens © The Huntington.”

this art vulnerable to loss. Ideological attacks on New Deal art and artists after World War II, began a decades-long era of neglect, suppression and destruction that continues to impact New Deal art today.

To expand our New Deal art advocacy, tin 2023 the Living New Deal launched the Advocating for New Deal Art (ANDA) initiative and began reaching out to experts in New Deal art. Among them is Barbara Bernstein, the Living New Deal’s Public Art Specialist, who founded the New Deal Art Registry, the first online archive of national scope to document New Deal visual art and artists. She is among the first generation of scholars, curators and allied professionals that in the 1970s and 80s, began to recover

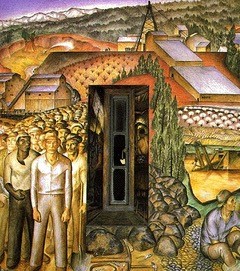

Land's End, by Dong Kingman, 1939

Kingman was one of a few Asian American artists hired under the New Deal. The work of New Deal artists of color is one of the areas of emerging research in the field of New Deal art studies. Courtesy, SAAM

New Deal art’s diverse and complex legacy.

One-on-one conversations with a range of New Deal art experts about how the Living New Deal might provide a platform for a New Deal arts community and helped shape the ANDA initiative’s goals of community building and collaboration; raising public awareness of New Deal art and its legacy; building momentum and resources within the field of New Deal art studies and

WPA Poster

WPA artists designed thousands of posters between 1936 and 1943. By publicizing classes, exhibitions, community activities and theatrical productions the posters served to democratize the arts. Many New Deal-era posters were discarded or lost—only about 2,000 WPA posters are known to exist today. Courtesy, Library of Congress

cultivating greater understanding and appreciation for New Deal art. More than fifty scholars, curators, collectors and other New Deal art professionals have signed on to participate.

An advisory board comprised of four distinguished art historians: Dr. Erika Doss (UT Dallas, Texas); Dr. John Ott (James Madison University, Virginia); Dr. Jody Patterson (Ohio State University, Ohio) and Dr. Jacqueline Francis (California College of the Arts, California), in collaboration with other ANDA participants, will help the Living New Deal engage with the critical issues facing New Deal art and provide opportunities to learn about them.

On February 14th, the ANDA initiative will hold its first public event, “Confronting the Legacy of New Deal Art in the Twenty-First Century,” a session at the College Arts Association Annual Conference, to be held in Chicago (February 14-17). If you plan to attend CAA, please come to the session! Learn more.