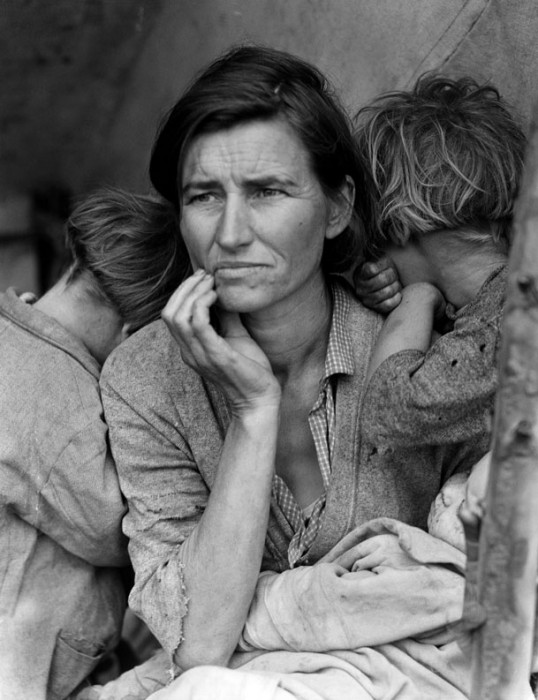

Migrant Mother

Florence Owens Thompson and her children. Nipomo, California, 1936

Photo Credit: Dorothea Lange, Courtesy LOC Prints & Photographs Division

Two children bury their heads into their mother’s shoulders. The mother is from Oklahoma. Her family is living in a migrant camp in Nipomo, California. She looks out from the canvas tent where lives with her ten children, her hand cradling her haggard face. She is Florence Owens Thompson, the subject of Dorothea Lange’s iconic 1936 photograph, “Migrant Mother.”

“We never had a lot, but she always made sure we had something,” Thompson’s daughter, Katherine McIntosh, recalled decades later. “She didn’t eat sometimes, but she made sure us children ate.”

Florence Owens Thompson worked the fields with her children alongside her. She could barely afford food, much less pay someone to care for her young family while she worked.

Childcare has historically been a dilemma for poor and working mothers alike. Believing that mothers should stay home with their children, social reformers pushed for pensions—not childcare. By 1930, nearly every state in the union had some form of mothers’ or widows’ pensions. But strict eligibility requirements and inadequate funding compelled many women to find jobs. With few options for childcare. Children would be left alone or brought along to the workplace, sometimes in hazardous conditions.

WPA Nursery School

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visits a WPA nursery school in Des Moines, Iowa in 1936.

Photo Credit: Courtesy FDR Library

Between 1933 and 1934, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) opened nearly 3,000 Emergency Nursery Schools (ENS), enrolling 64,000 students in 43 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands.

The History of Childcare in the U.S., describes the New Deal effort: “Unlike the earlier nursery schools, which were largely private, charged fees, and served a middle-class clientele, these free, government-sponsored schools were open to children of all classes. Designed as schools rather than as child care facilities, the ENS were only open for part of the day, and their enrollments were supposedly restricted to the children of the unemployed. They did, however, become a form of de facto child care for parents employed on various WPA work-relief projects,” according to Dr. Sonya Michel.

In 1943, the U.S. Senate passed the first, and thus far only, national childcare program, voting $20 million to provide public care of children whose mothers were employed in the war effort.

Childcare Program

The Lanham Act, adopted in 1942, was the first and, thus far, the only universal childcare program in the U.S.

Photo Credit: Gordon Parks, Courtesy LOC Prints & Photographs Division

In 1965 a bipartisan bill to establish national child-development and day-care centers was passed by both houses of Congress, but was vetoed by President Nixon, who dismissed it as “family weakening.”

A half-century later, there is still is no broad-based federally supported child care.

Though the need persists, childcare is increasingly beyond the means of many families. Under the current policies, most parents must cover the full cost on their own. Costs vary widely but the average cost of a sending a child to a day care center in the U.S. is $10,000 per year.

The federal government considers child care affordable when it is 10 percent or less of a family’s income. Low income and single parent families pay a much larger share of their income for child care and have less access to licensed childcare. Most young children spend time in multiple childcare settings. An estimated 15.7 million children under age 5 are in at least one childcare “arrangement” while their parents are working, at school, or otherwise unavailable to care for them. Currently, only 1.9 million children receive subsidized care through the federal Child Care and Development Fund.

Lunchtime

Children at childcare center in New Britain, Connecticut, while their mothers worked in the war industry, 1943

Photo Credit: Gordon Parks, Courtesy LOC Prints & Photographs Division

The U.S. trails behind other industrial nations such as France, Sweden, and Denmark, which offer free or subsidized childcare. “Unlike the United States, these countries use child care not as a lever in a harsh mandatory employment policy toward low-income mothers, but as a means of helping parents of all classes reconcile the demands of work and family life,” Dr. Michel point out.

Harry Hopkins, the New Deal’s Federal Relief Administrator, emphasized the need for such assistance. “The education and health programs of nursery schools can aid as nothing else in combating the physical and mental handicaps being imposed upon these young children in the homes of needy and unemployed parents,” Hopkins said.

Storytime

Teacher reading to young children at child care center, New Britain, Connecticut, 1943

Photo Credit: Gordon Parks, Courtesy LOC Prints & Photographs Division

The Biden Administration has proposed what could be a New Deal for childcare. The “American Families Plan” includes $200 billion for universal preschool for all 3- and 4-year-olds. If fully implemented, it would save the average family $13,000 and provide free or reduced-cost child care for the majority of working families with children under the age of six. The plan would affect about 9.76 million children nationwide.