The work of the Living New Deal is a lot like an archaeological dig. Archeologists discover lost civilizations with the benefit of new Lidar technology, but we come upon exciting new finds digging through old journals, newspapers and archives.

I recently exhumed an obscure 1939 WPA report from the UC Berkeley library. Far more than dry statistics, the report illustrates how the New Deal transformed the lives of small town and rural residents alike.

The report, Progress of the WPA Program, contains everything the Works Progress Administration accomplished in two rural counties—Mahaska, Iowa and Escambia, Alabama, and two cities—Erie, Pennsylvania and Portsmouth, Ohio. In all four places, government put hundreds of men, women and youth to work providing needed infrastructure and services to their communities in order to combat unemployment during the Great Depression.

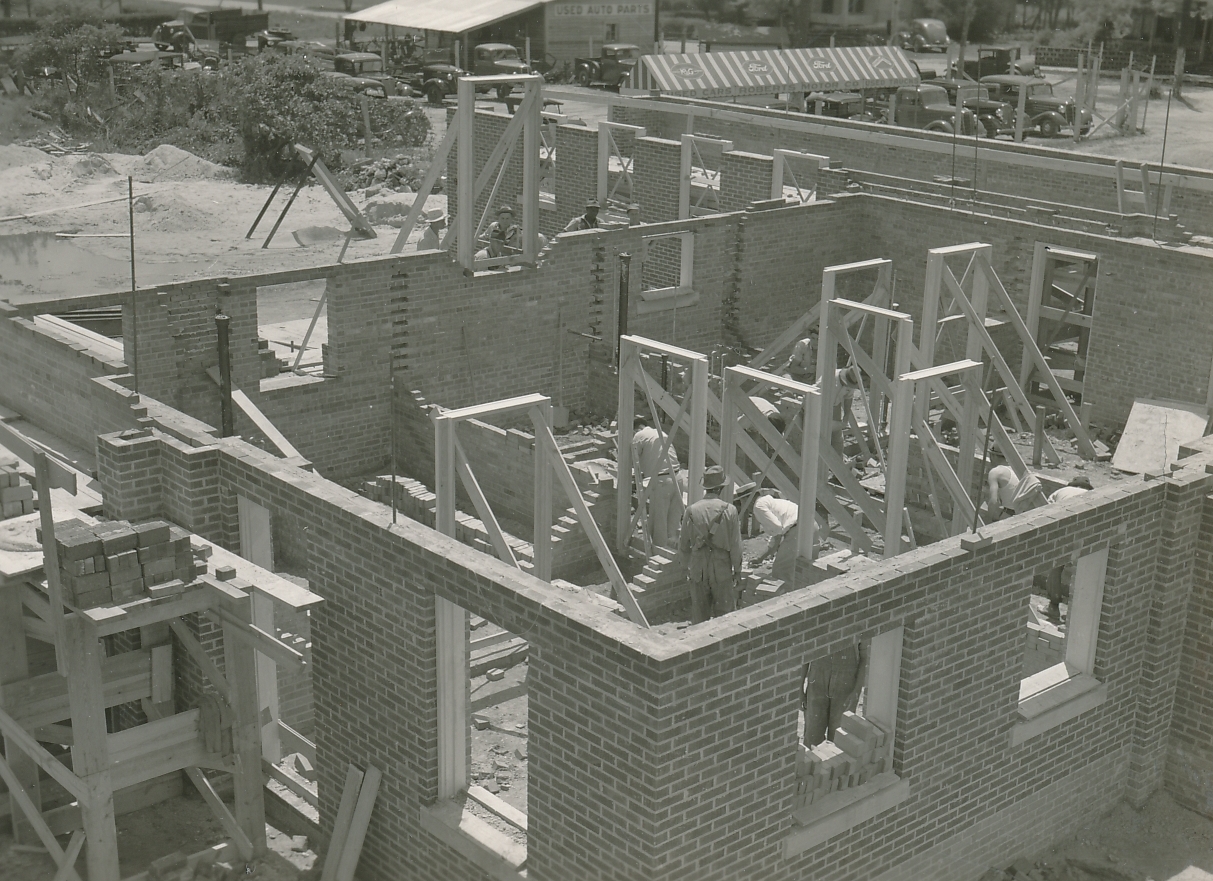

Sidewalk construction in Atmore, Alabama

The WPA laid 15,000 feet of sidewalk to this city.

Photo Credit: Courtesy National Archives

With the help of a nationwide network of volunteers, the Living New Deal’s growing website now documents more than 16,000 sites nationwide—parks, airports, city halls, stadiums, sewers, schools and more. The WPA report reveals that we have just scratched the surface, however. But since New Deal projects are rarely marked or mentioned in local histories, few, if any, of the New Deal’s improvements to their towns and counties are known to today’s residents.

The result is that many Americans mistakenly believe that the federal government does little or nothing for them or their communities, as Paul Krugman writes, even though the evidence of what good government can do is literally right under their tires and feet.

Dedication of WPA swimming pool in Edmundson Park

Oskaloosa, Iowa, 1937

Photo Credit: Courtesy National Archives

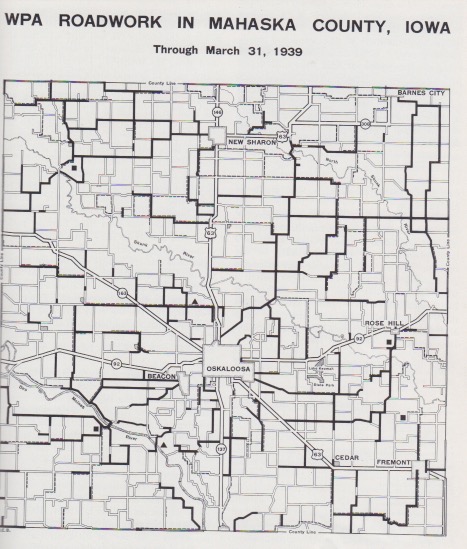

A map of Mahaska County, Iowa, for example, shows hundreds of miles of rural roads that the WPA graded and paved, enabling farmers to get their produce to market in all weather. Another map of Portsmouth, Ohio, shows the levees and five new pumping stations that saved the town from frequent flooding of the Ohio River. New storm drains did the same for Erie, PA.

During this time, 400 Erie women—many of them heads of households—sewed more than 200,000 garments to be given to the poor, while some 700 people were engaged in sixty-five orchestra and choral groups. Workers for the Federal Writers Project compiled historical information on a played-out coal region near Oscaloosa, Iowa, whose largely Welsh residents were given music classes. Oscaloosa’s Edmundson Park has so many WPA features, it qualified for the National Register of Historic Places.

Between 1935 and 1939, WPA expenditures in Iowa’s Mahaska County alone totaled $1,150,434—$20,595,724 in today’s dollars.

As extensive as the information in this report is on the WPA, it does not include the work of the PWA, CCC, or other New Deal agencies that benefitted rural as well as urban economies and ultimately lifted the country out of the Great Depression. Much of what government built through local labor still benefits millions of people today, some 80 years on.

With more digging, reports like Progress of the WPA Program as well as unpublished manuscripts, can be unearthed at libraries, town archives and historical societies across America. The Living New Deal is uncovering some of the best evidence anywhere of what a true government for the people once achieved—and could again—and making it freely available. Your support makes our work possible.