“First Snow” by Neva Coffey

Part of the New Deal collection at the GVCA, the scene shows New Yorkers at play, while the “Store to Let” sign acknowledges the Great Depression. Courtesy, GVCA.

The New Deal Art programs were a lifeline to struggling artists, of which New York had more than its share. Of the more than 10,000 artists commissioned nationwide by the WPA’s Federal Art Project (FAP) some 2,300 artists were in New York City.

A little-seen collection of paintings by WPA artists is on display in the village of Mount Morris, curated by the Genesee Valley Council on the Arts (GVCA). The artworks, most dating from 1936-1937, offer a window on life in New York during the Great Depression.

While many of the New Deal’s administrators believed that art could enrich the daily lives of all Americans, the main objective of the federal art programs was to provide jobs. The FAP hired thousands of unemployed painters, sculptors, muralists and graphic artists, with various levels of experience, and paid them a flat wage of $23.50 a week along with a stipend for materials. In addition to art production, the FAP offered art classes, held exhibitions and organized community arts centers through which many Americans were introduced to the arts for the first time.

"Blue and Gold” by Inez Abernathy

The foreground illustrates a rural setting in the midst of an urbanizing town in the background – a changing sociocultural climate in New York during the 1930s. Courtesy, GVCA.

In the 1930s, New York State opened tuberculosis sanatoriums in Mount Morris, Oneonta and Ithaca. Each facility was allocated a number of paintings by WPA artists. The landscape and still-life paintings that were sent to the Mount Morris Tuberculosis Hospital may have been chosen for their ‘restful’ subject matter. The paintings, by both American-born and European-immigrant artists, reflect the social realism popular at the time that FAP Director Holger Cahill praised as a “rediscovery of the American scene.” Changes underway, such as the expansion of cities, are depicted in paintings “Long Island Farm” by Philip Cheney and “Blue and Gold” by Inez Abernathy.

“Apples” by Fred Adler

FAP artist Adler was first assigned to paint scenes at an Iowa CCC camp.

This later still-life suggests the plight of minimally employed apple vendors on New York City streets during the Great Depression. Courtesy, GVCA.

“Apples,” by artist Fred Adler, suggests the plight of those minimally employed.

When the Mount Morris sanatorium closed in 1971, some 200 paintings were distributed to various Livingston County government offices. In 1999, the paintings were inventoried by the County and the Genesee Valley Council on the Arts, where the collection—on loan from the federal government—is currently on rotating exhibit. Many of the paintings are in their original frames bearing a “Federal Art Project” plaque on the front and typed tags on the back indicating the state of origin. All were produced in New York. Most of the artists lived in Manhattan. Until recently, little was known about them or their subsequent works.

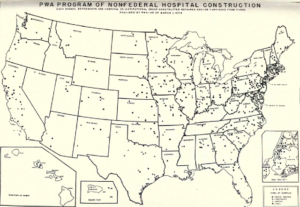

In 2018, students from a local college, the State University of New York at Geneseo, under the supervision of Professor Ken Cooper, photographed and catalogued the WPA paintings and researched the artists that produced them. This work led to an exhibit at the GVCA’s New Deal Gallery in 2019. The students also produced a digital exhibit, The Green New Deal: Art During a Time of Environmental Emergency”—that looks at these Depression-era paintings through a modern lens. The online exhibit includes a map showing where sea level rise now threatens some of the locations that inspired the paintings including several of Central Park.”

"Pelham Bay Park #1" by Moses Bank

Some landscapes depicted by FAP artists, such as Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx, are now endangered by rising sea levels. Courtesy, openvalley.org.

The Federal Art Project’s easel and print divisions provided an important lifeline at a time when opportunities for women and non-white artists were limited. The GVCA’s New Deal Gallery holds paintings by more than twenty women, including Dorothy Varian and Selma Gubin, as well as more than a dozen works by Japanese American artists, including Fuji Nakamizo and Tomizo Nagai. Varian, Gubin and Nakamizo all have works in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Other well known artists in the GVCA collection include David Burliuk and Fritz Eighenberg.

The paintings can be viewed online and at the New Deal Gallery, located at 4 Murray Hill Drive in Mount Morris, New York; for more information, visit www.gvartscouncil.org.