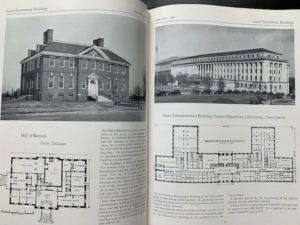

Department of the Interior Building, Washington, D.C.

Commissioned by the FDR Administration and now officially named for former DOI Secretary Stewart Lee Udall, the building contains a large collection of New Deal art. Courtesy, D.C. Preservation League.

In 1940, The Washington Post featured a 9-page photo essay on the capital’s new Department of Interior building. In photographs and text, the agency’s diverse functions were richly described. The building’s fashionable Art Deco or Moderne design and large, colorful public murals express New Deal progressive sentiments and faith in the government’s capacity to ensure the country’s prosperity. FDR described the building as “symbolical of the Nation’s vast resources that we are sworn to protect,” when he laid its cornerstone four years earlier and expressed his wish that the building’s construction represents the founding of “a conservation policy that will guarantee to future Americans the richness of their heritage.”

Harold Ickes (nickname "Honest Harold")

FDR’s Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes oversaw the design and construction of the department’s massive new headquarters. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

DOI Secretary Harold Ickes was intimately involved in the design and planning of the new building, and his selection of Native artists to paint several murals made clear that significant aspects of this heritage were to be found in its Indigenous cultures. The cafeteria, Indian arts-and-crafts shop and employee lounge were decorated with murals by Native artists. The building also included a gallery and a museum to house the agency’s Native art collection.

The Post’s coverage of the building included several photos of murals by Native artists and the American Indian arts and crafts displayed on government workers’ desks and office walls. Euro-American administrators were posed in front of murals related to the functions of their particular departments. Employees of Native ancestry were prominently featured in photographs. Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier was shown meeting with Navajo artisans Ambrose Roanhorse and Chester Yellowhair.

Laying the cornerstone

Department of Interior Building, 1935. From left, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Presidential Aide Gus Gennerich, Architect Waddy B. Wood, and Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes. Courtesy, Waddy Wood Papers, Architectural Records Collection, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

A caption reads “visitors to the new Interior Building must step on Indian mats and pass huge buffalo seals made into the floor. Bright Indian blankets and rugs hang in glass cases, and around almost any corner there may be a niche for Indian baskets or pottery. Indian murals in the penthouse cafeteria…rate among the best wall decorations in town.”

Many murals are the work of well-known American Regionalists such as John Steuart Curry and Social Realists like William Gropper. Several Native American artists were chosen for the murals project, including James Auchiah (Kiowa), Stephen Mopope (Kiowa), Gerald Nailor (Navajo), Allan Houser (Chiricahua Apache), Woody Crumbo (Creek/Potawatomi) and Velino Herrera (Zia Pueblo).

Interior Department Mural by Velino Herrera (Zia Pueblo)

Interior Department Building, Washington, D.C. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

The style of these works conforms to centuries-old traditions of representation—a significant contrast to the building’s Moderne style, which reflects its European modernist lineage. The subjects of the murals by the indigenous artists were equally tradition-bound, depicting traditional communal activities such as seasonal dances, buffalo hunts and arts-and-crafts production.

Interior Department Mural by Allan Houser (Chiricahua Apache)

Photo by Carol M. Highsmith. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

It is noteworthy that within a building styled to express the forward-thinking character of New Deal policies and programs, we find a large number of artistic expressions that convey a quite different message. The new DOI building and its art seem to convey the belief that America owes an important debt to its Native cultures. At the same time, however, it expresses the idea that Euro-Americans need a tradition-bound, constrained “other” for their own self construction as a people free and unconstrained.