Dust clouds over Dalhart, 1936

During the Great Depression, winds swept away parched topsoil, dooming farms, businesses and the national bank in Dalhart. Photographer unknown. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

“The thirties began in economic depression and in drought. The first of these disasters usually gets all the attention, although for many Americans living on farms, drought was the more serious problem,” Donald Worster wrote in his 1979 Bancroft Prize-winning chronicle, Dust Bowl. This could not be truer than in Dalhart, Texas, the epicenter of the Dust Bowl.

Born at the turn of the 20th century as an important railroad crossing in the northwest corner of the Texas Panhandle, Dalhart became a prosperous agricultural community, home to the XIT Ranch, then the largest cattle ranch in the world. But by the 1930s, extreme drought combined with the region’s notorious wind led to the soil erosion that ultimately devastated the town’s agricultural industry.

Abandoned farm near Dalhart, Texas

Photo by Dorothea Lange, Resettlement Administration, 1938. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Things began to turn around in 1934 with the emergence of the New Deal, when the USDA’s Soil Conservation Service chose Dalhart, the county seat, for one of the nation’s first erosion-control demonstration projects—the first to focus solely on wind erosion.

Initially manned by the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration, these rehabilitation projects restored grasslands in areas not suitable for farming and introduced new methods of moisture retention, such as terracing, crop rotations and contour plowing. The success of the projects combined with new federal loan programs incentivized farmers to adopt the new practices, which boosted the local economy and popularized conservation practices. By 1936, more than 40,000 farmers throughout the region had adopted the new methods, accounting for more than 5.5 million acres of contour-listed conservation.

The drought committee from the Soil Conservation Service surveys sand dunes just a few miles north of Dalhart.

Photo by Arthur Rothstein, Farm Security Administration, 1936. Courtesy, The New York Public Library.

These restoration programs revived the agricultural economy of Dallam County, today one of the largest agricultural producing counties in Texas by value, with the city of Dalhart serving as an agribusiness hub for a region stretching across five states.

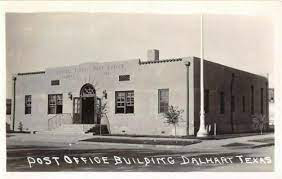

The impact of the New Deal didn’t stop at the agricultural revival of Dalhart’s farmlands. The destruction caused by the Dust Bowl also meant the city itself needed rehabilitation assistance. The WPA was responsible for damming the Rita Blanca Lake (now a city-owned recreation site), paving downtown streets, constructing underpasses to accommodate vehicle and rail traffic and building Dalhart’s downtown post office, today owned by Vingo Vineyards Winery.

Vintage Postcard, Dalhart, Texas Post Office

The former Dalhart, Texas post office building was constructed with federal Treasury Department funds in 1934.

Dalhart owes much of its mid-century revival to the New Deal and the impact of the Soil Conservation Service. Today, the City is committed to historic preservation efforts, many of which highlight the New Deal-era. Restoring Dalhart’s historic downtown has become a priority.

Paved with bricks laid by WPA workers, Denrock Avenue is lined with historic storefront buildings that, like the city itself, withstood the hardest of times. Restoring and preserving this history is part and parcel of the vision for the city’s future as a destination for visitors, a vibrant commercial center and a source of pride for Dalhart’s resilient residents.

WATCH: Dalhart Dust Storm

Newsreel footage reveals the devastation of soil erosion and dust storms to the town and farms around the panhandle town of Dalhart,1930s. Courtesy, Texas Archive.org