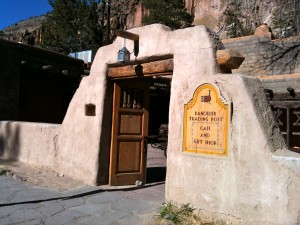

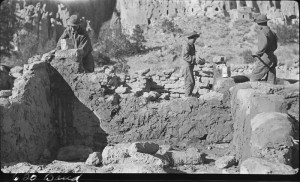

Ever since the New Deal’s National Youth Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and a brief flurry of public-spiritedness during the Kennedy years, America has minimized both expectations and opportunities for public service. Fewer Americans than at any time in our history — less than one half of 1 percent— are engaged in public service (including those serving in the military). Yet, the enormity of our country’s current challenges and chronic unemployment point to the need to give young people the chance to work helping their communities.

Here’s why we need a National Youth Service (NYS).

1. A NYS would be a job-creation program. Sure, it would be expensive, but 6.7 million young people between the ages of 18 and 24 who are out of work and out of school currently cost taxpayers $93 million per year.

2. A NYS would be an immediate and lasting stimulus to our economy. Requiring participants to send some of their pay home (as the CCC did of its recruits) would also help struggling families.

3. A NYS would have long-term benefits for both the individual and society. The youth would obtain marketable job skills through rebuilding infrastructure, installing green energy, restoring the environment and helping during natural disasters.

4. Like the CCC, NYS youth would work and live together, helping break down barriers arising from the extremes of wealth and poverty.

5. NYS “graduates” would qualify for GI Bill benefits now limited to military veterans, encouraging college attendance and reducing student loan debt.

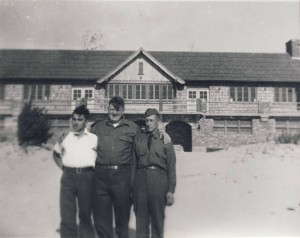

6. Military service would be one among many NYS job options, addressing the disparity of having a tiny segment of our young people—mostly disadvantaged—serving the nation.

7. A NYS could serve to re-integrate military veterans into society.

8. A NYS fitness program would help young people lead healthier lifestyles.

9. Like the CCC, a NYS would help young people stay out of trouble that could lead to prison.

10. Most important, by offering them a greater stake in their country’s future and their own, a NYS would show young people that they are valued.