More than eighty years after President Franklin Roosevelt established the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), it remains one of the most memorable of the New Deal programs. Endearingly called FDR’s “Tree Army,” the CCC was key to an unprecedented era of environmental restoration and parks development that took place in the 1930s. Photographs of CCC “boys” at work and enjoying camp life played an important role in promoting both the parks and the CCC’s achievements.

The task of documenting the CCC, especially in western national parks, belonged to George Alexander Grant. A Pennsylvania native, Grant fell in love with the West’s rugged landscapes while stationed in Wyoming during World War I. Laboring in eastern factories after the war, Grant yearned to return to the West. He landed a seasonal job at Yellowstone in 1922. There he picked up a camera—perhaps for the first time—and produced images that impressed the park’s Superintendent Horace Albright. Grant reluctantly turned down a coveted ranger position at Yellowstone in hopes of working for the Park Service as a photographer. Six years of correspondence with Albright–and Albright’s appointment to Director of the National Park Service in 1929– led to Grant’s becoming the Park Service’s first staff photographer. Just months later, the nation was plunged into the Great Depression.

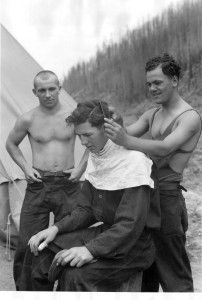

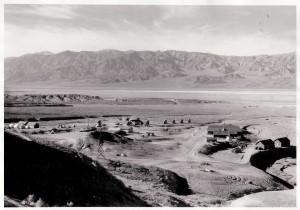

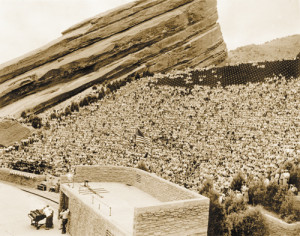

By 1933 Grant was the chief photographer of the National Park Service and on the front lines of a golden age for national parks. That year marked the creation of the CCC and FDR’s executive order nearly doubling the size of the parks system through the addition of national monuments, battlefields, and historic sites. Grant would spend the next seven years chronicling the CCC’s work in national parks. His finely detailed images depict men laboring on the shores of Jackson Lake in the Grand Tetons; pausing for lunch amid the grandeur of Glacier National Park; restoring historic fortifications at Vicksburg National Military Park; clearing snow from roadways in Rocky Mountain National Park; and tackling camp chores like laundry and getting a haircut.

Like the photographs of his friend and contemporary, Ansel Adams, Grant’s vivid black-and-white photographs were seen by millions of Americans. Through these images, Americans could see the results of the CCC’s labors and the physical and emotional sustenance the work provided its enrollees. Yet, Grant has remained virtually unknown because nearly all of his published photographs were simply credited “National Park Service.”

The Park Service’s 2016 centennial year is an ideal time to remember the contributions of this unknown elder in the field of outdoor and landscape photography.

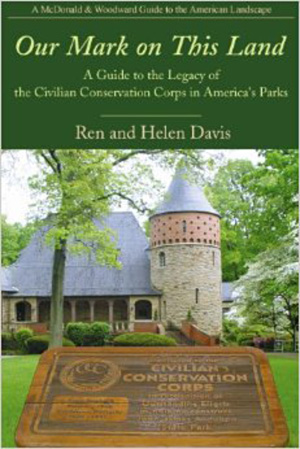

Ren and Helen Davis are writers and photographers based in Atlanta, Georgia. Their newest book, Landscapes for the People: George Alexander Grant, First Chief Photographer of the National Park Service (University of Georgia Press, 2015, $39.95) complements the National Park Service Centennial commemorations. The Davises have co- authored six books, including Our Mark on This Land: A Guide to the Legacy of the Civilian Conservation Corps in America’s Parks, published in 2011.