Just as the controversy over the Victor Arnautoff murals in San Francisco’s George Washington High School draws national and even international attention, New Deal era murals in the University of Oregon’s main library stir debate over public art, representations of gender and race, and conditions for an inclusive campus environment. The future of the Knight Library murals, however, was decided in a much different way, with a much different conclusion–and offers a model for engagement with challenging public art.

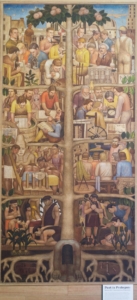

The controversy surrounding the Knight Library murals began several years ago as students launched successive protests over three murals installed as part of the 1937 New Deal-era library’s east and west stairwells. The focus was on the WPA artists Arthur and Albert Runquist’s pictorial murals “The Development of Science” and “The Development of Art.” The Runquist brothers, graduates of the University of Oregon, shipyard workers and regionally known artists, were associated with progressive politics. Today’s critical analysis, however, draws attention to their selective narrative. As shown in “The Development of Science,” progress is suggested by a tree portraying eight vignettes from the early human discovery of fire and agriculture to science in the early 20th century. Its emphasis on Western civilization and a limited representation based on gender and race normalizes forms of privilege that university values presumably should challenge. Certainly, twenty-first century UO students have.

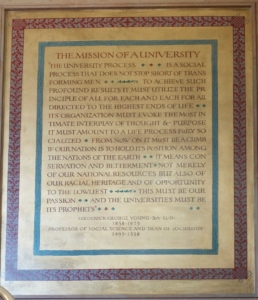

Mural, "The Mission of a University"

The words “our racial heritage” were defaced with red ink.

Photo Credit: Howard Davis

The mural that draws the greatest fire, however, is titled “The Mission of a University,” inscribed on the wall as if it were a medieval manuscript. The text borrows from a 1909 speech by UO Sociology professor Frederick Young in which he argues the service required of a university, contending: “From now on it must be a climb if our nation is to hold its position among the nations of the Earth. It means conservation and betterment not merely of our national resources but also of our racial heritage and of opportunity to the lowliest.”

A student petition, filed in November 2017, called for the University to remove it—mobilizing over 1,750 students in the process. During the summer of 2018, the mural was defaced. A protestor highlighted the phrase “racial heritage” with red paint and left a taunting note: “Which art do you choose to conserve now?”

The library administration’s response was to clean the mural, send the note to be archived as part of the campus’ history of protest, and to place a placard next to the mural acknowledging the defacement, yet calling for “continuing our cross-campus project to contextualize these artifacts for educational and cultural reasons, and for allowing them to remain uncensored as evidence of the embedded racist and sexist legacy against which many of us still struggle.”

Librarian’s Response

Placard addressing vandalism of the Knight Library Mural

Photo Credit: Judith Kenny

Education rather than erasure has been the consistent response from the administration. This might, in part, be understood as an aspect of its conservation responsibilities for a building with historic preservation requirements. Completed in 1937, the Knight Library was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1990. It exemplifies the quality of public building that could be produced through the financing of the New Deal’s PWA and WPA programs and the creativity inspired by the WPA Federal Arts Program. Because the murals are embedded in the library’s walls, removal would likely destroy them. But the conservation of a building, as the placard cited, is less an issue than is the uncensored evidence of an “embedded racist and sexist legacy.”

Even as protests took place, in February 2017, Adrienne Lim, Dean of Libraries, launched the Knight Library Public Art Task Force, charged with several tasks. Just last month, it submitted its report to the University Senate.

The first task was to set up a committee of library faculty members to work on a guide to the library’s historic resources. The second, overseen by a committee of students and faculty members, involved conducting a public forum, “Public Art, Cultural Memory, and Anti-Racism” to explore public art as an artifact representing past and contemporary values. The third task undertook a juried exhibit of student art that reflected contemporary values, titled “Show Up, Stand Out, Empower!”

A public forum, “Public Art, Cultural Memory and Anti-racism,” discussed the implications of removing the “The Mission of the University” mural. Professor Laura Pulido, Head of the Department of Ethnic Studies, argued against removal, “I understand that many want to tear down racist symbols of the past for reasons I respect. But I am opposed to such erasures,” she said, adding, “The only way to move forward to not be held hostage to our past is to engage the past.”

Ms. Kenny,

Malissa Minthorn referred the website to me regarding the Indian CCC projects in Oregon. I’m the principal author of the NPS study you discussed with her. If you would like to talk let me know—[email protected]

Tom Hampson