In 2015 we celebrated the 80th anniversary of the Works Progress Administration. The largest and most ambitious effort of the New Deal, the WPA provided millions of Americans the opportunity to work—reviving the economy and bringing hope and progress to virtually every city, town, and rural community. In this newsletter we reflect on the New Deal’s legacy in its many forms—an extraordinary couple’s New Deal romance; setting the record straight on what really ended Great Depression; tackling the injustice of poverty in an era of great wealth. Thank you for your stories, your interest, and your support.

- Home

- /

- News, Articles & Newsletters /

- The Fireside

- /

- Winter 2016

Winter 2016

A “New Deal” Romance

The photograph of my parents, Gene and Betty Kingman, taken amidst the natural wonders of Mesa Verde National Park, foretells a love story that lasted 39 years.

My dad, Eugene Kingman, was a prolific artist drawn to the beauty of the American West. During the Great Depression he travelled from his home in Providence, Rhode Island, to capture on canvas the scenic treasures of the national parks.

My mom, Elizabeth Yelm, was a ranger and museum assistant at Mesa Verde at a time when few women worked for the National Park Service. Mom absolutely loved her job and I am ever proud of her for applying again and again until she finally landed it!

She was a bright, strong-minded woman who received a scholarship to study Anthropology at the University of Denver. She appeared in “Who’s Who” as one of the first women there to earn a Master’s degree.

Mom and Dad met on one of her guided tours of the cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde. According to Mom, it was her storytelling around the campfire that led Dad to fall in love with her. When she resigned from her ranger job a year later to marry him, all of her park colleagues (mostly men) signed her ranger hat.

Over the years Mom and Dad forged an exceptionally strong partnership. Mom valued immensely Dad’s artwork and kept a record of every painting, lithograph, and mural he created, as well as his designs for museum exhibits—his specialty.

Dad earned degrees in Fine Arts and Geology at Yale that combined with a fascination with the national parks, led to some extraordinary assignments. Horace Albright, the first director of the National Park Service, commissioned him to paint seven of the most popular national parks—Yosemite, Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, Crater Lake, Sequoia, Grand Teton, and Mt. Rainier—for the 1931 Paris Expo. Dad’s spectacular plein air oil paintings of Old Faithful and Grand Teton are part of the permanent collection at the National Park Service headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Improving national parks and promoting tourism were among the New Deal’s efforts to grow the economy. In March 1937, The National Geographic published thirteen of Dad’s Yosemite and Crater Lake paintings to illustrate an article on how these parks evolved geologically over millennia.

During the New Deal, Dad was awarded commissions for post office murals in Kemmerer, Wyoming; Hyattsville, Maryland; and East Providence, Rhode Island.

After serving as a cartographer in WWII, he became the director of the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, and stayed for 22 years. He then got hired as Director of Exhibit Design and Curator of Art at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, where he passed away in 1975.

After Dad died, my mom moved to Santa Fe. She worked with archeological scholars at the School of American Research well into her 80s.

Whenever I look at the cherished photo of my parents at Mesa Verde, I conjure up the campfire that sparked my parents’ lifelong romance. I’m not sure why Mom isn’t wearing her ranger hat in the picture. That hat meant a lot to her. In fact, I wore it during her memorial service in 2005 when we sang one of Mom’s favorite tunes: “Happy Trails to You.”

Forgetting Decency

Flop House

A 1937 painting by Edward Millman, Flop House depicts the despair that the New Deal sought to address.

Today’s San Francisco, even more so than other successful cities, is a study of jarring contrasts as sleek skyscrapers rise from streets on which ever-increasing legions of the desperate, destitute, and demented sleep, beg, and offend the sensibilities of tourists and residents alike. Poverty—with all its pathologies—has reached crisis proportions in tandem with pathological wealth.

President Roosevelt’s administration dealt with many of these same problems. By contrast, Washington today is ignoring or actively worsening the social ills that the New Deal tackled head on.

Based on what he witnessed in San Francisco, the 19th Century political economist Henry George explained in his bestseller Progress and Poverty how concentrated wealth produces widespread poverty.

Homeless in San Francisco

Homeless: I used to be your neighbor Source

Such social inequality is the subject of much of the art produced during the New Deal. The Federal Theatre Project’s widely seen play, One-Third of a Nation, was based on Roosevelt’s 1936 inaugural declaration in which he said he saw “one third of a nation ill-clad, ill-housed, and ill-fed”— and promised to use the federal government to do what the market could not do to alleviate that disgrace.

It is telling that the opulent San Francisco Museum of Modern Art occupies a site in a neighborhood once known for flophouses—the cheap housing that urban redevelopment cleared away to accommodate the city’s expanding financial and retail districts. Flophouses gave seasonal workers and those too old to work marginal shelter, but even as that housing was being eliminated by redevelopment, so were their jobs by automation, off-shoring, and market downturns.

Nowhere are the multiple dysfunctions associated with poverty more evident than at downtown San Francisco’s United Nations Plaza. A front-page article in the San Francisco Chronicle—“Complaints skyrocket over syringes on streets in S.F.”—accompanied a photo of a city worker collecting used needles in a long-neglected fountain commemorating the founding of the United Nations in 1945 just three blocks away.

Homeless Man Sleeps on a Bench

FDR’s Second Bill of Rights: “The right of every family to a decent home.”

Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights laboriously shepherded through the UN by Eleanor Roosevelt in 1948 in hopes of ending future wars reads:

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing, and medical care and social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age, or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

It codified much of what Franklin Roosevelt had succinctly enunciated as a Second Bill of Rights in his fourth inaugural address, including “The right to a useful and remunerative job” and “The right of every family to a decent home.

Labor Secretary Francis Perkins recalled that “”Decent’ was the word (Roosevelt) often used to express what he meant by a proper, adequate, and intelligent way of living.”

That we have opted for indecency as a way of life is evermore evident on our streets and battlegrounds as they become one and the same.

Did the New Deal Cure the Great Depression?

FDR Flashes the Victory Sign, 1942

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945), the 32nd President of the United States, at his estate in Hyde Park, New York.

Photo Credit: Keystone/Getty Images

The Great Depression, the worst crisis in American history, brought the country to its knees by 1933 when Franklin Roosevelt took office. FDR and his team launched the New Deal to help get the country back on its feet. They succeeded, yet the myth persists that the New Deal had little effect on economic recovery and only World War II ended the Depression.

The proximate cause of the Great Depression was the financial meltdown that began in October 1929. Stock prices nosedived, millions defaulted on mortgage payments, and thousands of businesses and banks were shuttered.

The real economy was going into recession well before Black Friday, when all hell broke loose. Investment shrank, wages were slashed, layoffs multiplied, and consumer demand shriveled, propelling the economy into a downward spiral. By early 1933, GDP had fallen by half, industrial output by a third, and employment by one-quarter.

A key accomplishment of the New Deal was to get the U.S. financial house in order. Failing banks were culled, deposit insurance instituted, homeowners bailed out, and mortgages guaranteed. The Federal Reserve loosened up the money supply and credit began to flow again.

Meanwhile, billions were pumped into the economy through emergency relief funds and public works programs, from the CCC to the WPA. Not only were millions of desperate American put to work, their families had spending money to stimulate aggregate consumption.

Furthermore, federal spending shot ahead of tax revenue, creating a large budget deficit. FDR didn’t believe in deficits, but was willing to try anything, thus inventing ‘fiscal policy’ even before economist John Maynard Keynes gave it a name.

The economy took off, reaching double-digit growth rates. By 1937, the Great Recovery had pushed output, income, and manufacturing back to 1929 levels. Then recession hit in 1937-38, dropping output by a third and driving unemployment back up. Three things contributed to the setback: FDR tried to re-balance the budget; Social Security taxes kicked in; and the Federal Reserve tightened money supply.

Nevertheless, growth resumed in 1939 and regained its long-term trajectory before war broke out. The big exception was unemployment, which stayed above 10 percent, forever marring the New Deal’s reputation. Worse, a key study exaggerated joblessness by not counting the millions working in federal work programs.

World War II brought full employment through military recruitment and full-tilt production, with the federal government running more massive deficits than the New Deal ever dared.

To be sure, recovery cannot be ascribed only to the New Deal. By the 1920s, the American economy was the largest in the world and the assembly line, electricity, chemicals, and petroleum had unleashed a new Industrial Revolution. Advances in productivity continued through the 1930s. Dramatic improvement in transportation was helped by the New Deal’s extensive road building. The downside was closure of obsolete factories and railways, terminating millions of jobs, which explains much of the unemployment that remained despite the Great Recovery.

Colorado Springs Saves Its New Deal Murals

The City Auditorium has served as Colorado Springs favored venue for public events since 1923. In the past, circuses, dance, and music reigned in the Classical Revival building. In recent years it has played host to cat shows, wrestling, and psychic fairs.

In 1934, under the Public Works of Art (PWAP) section of FDR’s New Deal, Boardman Robinson, the Southwest Coordinator of New Deal Art, and city officials selected two artists to paint lunette murals in the auditorium’s foyer. Both murals were to represent the focus and purpose of the public building.

Both artists were members of the Broadmoor Art Academy, an early oasis of art and culture in Colorado Springs. It was academy instructor George Biddle who wrote to his former classmate at Groton, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, proposing a program for artist relief. Many of the academy’s instructors and students were soon hired under New Deal art programs to paint murals.

The Arts Mural by Tabor Utley

One of two recently conserved murals in the City Auditorium in Colorado Springs.

Tabor Utley taught landscape painting at the academy. His lunette at City Auditorium depicts the performing arts—dance, theatre, orchestral music, and a gospel choir. Facing it is a lunette painted by Utley’s student, Missourian Archie Musick. “Hard Rock Miners,” is Musick’s first major mural. It depicts the history of the area—gold mining and the cultural environment that the industry supported. Musick went on to paint New Deal murals at post offices in Red Cloud, Nebraska and Manitou Springs, Colorado.

When City Auditorium was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992, the murals were in bad shape, suffering from cracks in the plaster, moisture in the walls, and layers of accumulated smoke and grime.

Unfortunately, conservation was a low priority given the City’s budget and there was confusion about who was responsible for the care of the murals.

In 1998, Archie’s daughter, artist Pat Musick, and I decided to take on the conservation project ourselves. The then-director of the building became our third mover and shaker.

Hardrock Miners by Archie Musick

One of two recently conserved murals in the City Auditorium in Colorado Springs.

Through much networking, fundraising, and lobbying, we were on our way to getting the City to be our partner. Our efforts led to a grassroots campaign, “A New Deal for the New Deal of Southern Colorado.” The Pikes Peak Arts Council became our fiscal sponsor, which enabled us to apply for grants not available to the City. We managed to secure funding from two local organizations, The El Pomar Foundation and the Gay and Lesbian Fund for Colorado.

We raised $10,000, which the City matched, to hire a local conservator. A lab analysis confirmed that both murals were painted in oil. Conservation began in early 2004 to stabilize, consolidate, and clean them. The restoration included new lighting and a Data Logger to monitor environmental conditions.

We held a public unveiling of the newly conserved murals, and received an award from the Arts, Business, and Education Consortium. We were invited to the annual Saving Places conference in Denver, hosted by Colorado Preservation, Inc, and were surprised to find our project on the cover of the conference issue of their magazine.

A National Monument to the CCC

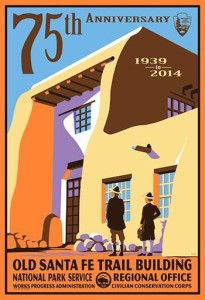

National Park Service Southwest Hdq 1937

The Old Santa Fe Trail Building, 1937

Photo Credit: National Park Service

The Old Santa Fe Trail Building is considered a hallmark of the Civilian Conservation Corps’ many contributions to the national parks.

Built between 1937 and 1939, and designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1987, the building on Museum Hill is the work of the young men who served in the CCC in New Mexico during the Great Depression. The Spanish/Pueblo Revival-style adobe building is a testament to their work and, in particular, to the Native American and Latino New Mexicans whose commitment and craft are manifest in this beautiful building.

The building was constructed largely by hand using local materials. Logs for the vigas and corbels came from the CCC camp in nearby Hyde Memorial State Park; the highly polished flagstone in the lobby, conference rooms, and portal came from a large ranch near Glorieta; posts supporting the roofs above the portales are peeled ponderosa pine logs. The CCC boys also produced many of the building’s furnishings.

Old Santa Fe Trail Building

National Park logo in the portico. Source

The historic building served as the Southwest headquarters for the National Park Service from 1939 to 1995, when the NPS relocated its regional office to Denver. In tribute to the region’s history and multicultural heritage, the building had been managed as though it were a unit of the National Park System. Due to budget cuts it now has only limited public use.

There is no National Park dedicated to telling the story of the millions of people who got jobs and gained skills while carrying out projects of lasting public benefit through New Deal programs like the CCC and the Works Projects Administration. A formidable coalition has mounted an effort to designate the Old Santa Fe Trail Building a National Monument—the National Trust for Historic Preservation, National Parks Conservation Association, National New Deal Preservation Association, Historic Santa Fe Foundation, the Coalition of National Park Service Retirees, and the Living New Deal among them. We are asking President Obama to use his authority to designate this historic building a national monument.

Old Santa Fe Trail Building Anniversary Poster

Poster commemorating the historic CCC-constructed building

We are seeking letters of support. Please email the President and contact your elected representatives asking them to preserve the Old Santa Fe Trail Building as a national monument in honor of those whose labors during the hardest of hard times still inspire us today.

Book Review: The Worst Hard Time, 312 pp

On Black Sunday, April 14, 1935 a cloud two hundred miles wide carrying more than 300,000 tons of topsoil blackened the skies over the Great Plains. People lost their way as the wall of darkness rolled in; stores and schools… read more