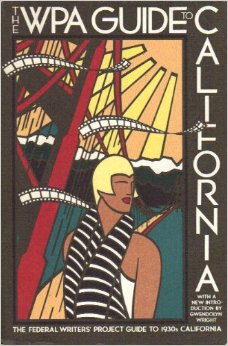

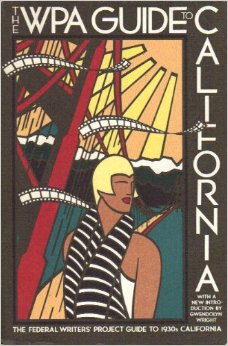

WPA Guide to California

1939

In another sign that America is waking up to the rich legacy left to us by the WPA, the American Guide Series— out of print since the 1940s—is being reissued as quality paperbacks, which are selling well. Over the last decade, university presses and other publishers have rediscovered the value of these well-researched, vividly written and wide-ranging guidebooks. Though the books are now 70 years old, “they are no more obsolete than any other great works of American literature,” says David Kipen, who wrote introductions to the recently reprinted WPA guides to San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego.

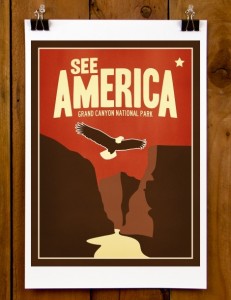

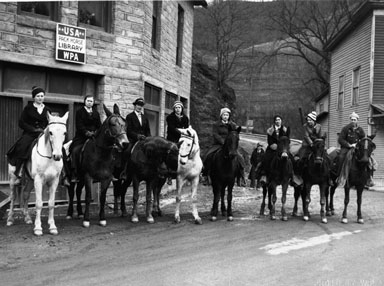

The guidebooks are probably the best-known publications of the WPA’s Federal Writers Project. Like other WPA arts projects, the American Guide Series had multiple goals. It employed out-of-work writers, fostered a sense of local pride, and promoted much-needed tourism. While the federal government paid the salaries of some 6,000 writers of the series, each state was responsible for printing and distributing the books.

The guides more or less followed a standard format—covering the geology, history, industry, agriculture, government, and natural resources of each of the 48 states and the District of Columbia. Major cities, large towns, and characteristic regions were discussed in detail, and sometimes embellished with cultural trivia and regionalist charm Readers could find out, for example, that Mays Landing, New Jersey is the national capital of nudism; that Nevadans like to eat at lunch counters; and that the favorite names for Tennessee coon dogs are Drum, Ring, Gum, and Rip.

WPA Guide to New York City

1939

The guidebooks were so popular that the series expanded to cover 27 individual cities; fifteen regions, such as the Berkshire Hills and Monterey Peninsula. Many of the guides had annotated “motor tours” and some were exclusively dedicated to destinations, such as “Ghost towns of Colorado,” and “The Ocean Highway: New Brunswick, New Jersey to Jacksonville, Florida.”

One of the most interesting of American Guide Series is “Washington City and Capital.” Originally published in 1937, it is replete with fascinating history and lore, but President Franklin D. Roosevelt questioned its utility as a guidebook because it weighs four pounds. A condensed, more portable size was subsequently published.

Like the murals the WPA commissioned for government buildings, these books assured Americans that their local sights and activities were part of a great American story worthy of being captured in print or paint.

The American Guide Series died out with the rest of the New Deal in the early 1940s, but the books became sought-after collectors’ items and are still used by travelers and valued by history buffs. Indeed these guidebooks remain useful and entertaining. They offer, in Kipen’s words, “a keepsake of all that’s lost, a Baedeker to how much survives, and an example of what writers and America once did for each other, and might again.”

Barbara Bernstein founded the online

New Deal Art Registry and is now the Public Art Specialist at the Living New Deal Project.