Federal Writers' Project Poster

American Guide Series

Photo Credit: Courtesy Library of Congress

In the first half of the 20th century—before he fell through the cracks of history—Henry Alsberg’s byline appeared regularly in newspapers and magazines. When Harry Hopkins tapped him to lead the Federal Writers’ Project in 1935, Alsberg had already lived a remarkable life.

Born in New York City in 1881, Alsberg spent the 1920s as an activist and writer in the U.S. and abroad. He worked on behalf of political prisoners, reported on the geopolitical changes in Europe and Russia for The Nation and other publications, and aided Jewish refugees fleeing pogroms in Eastern Europe. He produced and wrote plays at the Provincetown Playhouse and the Neighborhood Playhouse. In 1930, he helped Emma Goldman edit her autobiography. His close friendship with Goldman developed at least partially from her open stance on homosexuality. As a gay man living in horrendously dangerous times, Alsberg found a safe haven in her company.

By the time of the Great Depression, the boundlessly energetic Alsberg had suffered economic as well as personal setbacks. Freelance writing jobs were scarce. A contract with the Metropolitan Opera House to adapt one of his plays fell through. But Roosevelt’s New Deal brought a promising new deal for Alsberg.

Alsberg with Eleanor Roosevelt, an ardent FWP supporter

At WPA Exhibit in Washington, D.C., 1938

Photo Credit: Courtesy of National Archives

At age 53, he landed a writing job with the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and authored America Fights the Depression, a large-format book promoting the accomplishments of the Civil Works Administration (CWA). Then, he brought his progressive beliefs to the Federal Writers’ Project, which he headed from 1935-1939.

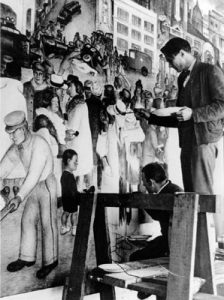

Under Alsberg’s guidance, the Project—dubbed by Pathfinder Magazine as “a 20-million word experiment in collective writing”—produced hundreds of books. The highly acclaimed American Guide series detailed the histories and cultures of each of the then-48 states, Alaska, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico, and provided descriptions of every major city and town.

Among the 10,000 unemployed people hired by the FWP over its 8-year existence were many up-and-coming writers, including John Cheever, Margaret Walker, and Richard Wright. Ralph Ellison, May Swenson, and others collected oral histories for the FWP, preserving by the thousands the life stories of former slaves, immigrants, factory workers, and other Americans who didn’t typically make it into the history books.

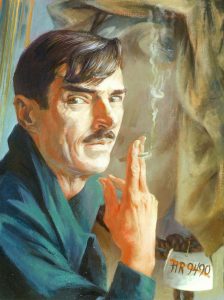

Henry Alsberg, Director of the Federal Writers' Project

Testifying at House UnAmerican Activities Committee hearing, 1938

Alsberg and Hallie Flanagan, his counterpart at the Federal Theatre Project, constantly battled with anti-New Deal forces. Their mutual nemesis, Congressman Martin Dies, chair of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), led the opposition that ultimately defunded both projects in 1939. Colonel Francis Harrington, Harry Hopkins’ successor as head of the WPA, ordered Alsberg to resign, but he stubbornly refused to leave while he was in the midst of ushering a number of books to publication. Harrington fired Alsberg; the FWP was renamed the WPA Writers Program, and continued in a diminished capacity under state auspices until its closure in 1943.

After a brief speaking tour, Alsberg resumed freelance writing and returned to New York City, living for a time next to Bonnie’s Stonewall Inn—later renamed the Stonewall Inn—today a landmark of the gay rights movement. In 1942, he returned to Washington D.C. as an editor for the Office of War Information. But that didn’t last long. The Civil Service Commission investigated Alsberg for being in an “immoral,” homosexual relationship, forcing him to resign.

FWP display at the 1939 New York World’s Fair

Oversized American Guide books placed on a U.S. Map

He returned to writing and working as an editor for Hastings House into his 80s. In his final years, he moved to Palo Alto to live with his sister, a civil rights activist. He often visited City Lights bookstore in San Francisco, where his friend, Vincent McHugh, a former New York City FWP editor, was involved in the Beat poetry scene. After Alsberg’s death in 1970, McHugh recalled their FWP years: “We were one of the Berkeleys of the 1930s.”

Alsberg and the Federal Writers’ Project changed the literary landscape of America. We can look forward to this legacy expanding exponentially as more original FWP materials become digitized.

Susan Rubenstein DeMasi is the author of the 2016 biography, Henry Alsberg: The Driving Force of the New Deal Federal Writers’ Project. She is a visiting scholar in this summer’s National Endowment for the Humanities program, “The New Deal Era’s Federal Writers’ Project,” as well as a contributor to an upcoming book on the literary legacy of the FWP, edited by Sara Rutkowski, for the University of Massachusetts Press.

[email protected]