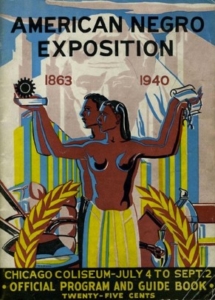

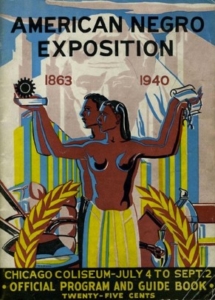

Official program and guidebook

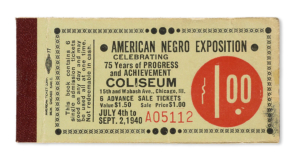

American Negro Exposition that opened the Chicago Coliseum on July 4, 1940.

Photo Credit: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

The official program of the Diamond Jubilee of Negro Progress, which opened at the Chicago Coliseum on July 4, 1940, proudly states, “This is the first real Negro World’s Fair in all history…The Exposition will promote racial understanding and good will; enlighten the world to the contributions of the Negro to civilization and make the Negro conscious of his dramatic progress since emancipation.”

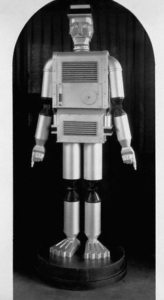

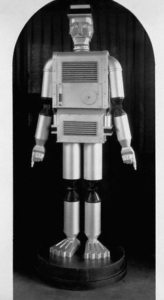

Duke Ellington played during the Bronze America beauty contest. Arctic explorer Matthew Henson was lauded, as was Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, the man who performed the first successful open-heart surgery. The popular dance team, Pops and Laurie, performed in a production of “Tropics After Dark.” Mechanical Man greeted visitors to the Labor section of the fair. Paul Robeson sang ‘Ol’ Man River’ and poet Langston Hughes co-wrote a musical pageant for the Jubilee. Not to be outdone, choral director J. Westley Jones led a chorus of voices, a thousand strong, under seven large religious murals painted by Aaron Douglas.

Truman Gibson, executive director of the American Negro Exposition

With replica of Springfield’s Lincoln Monument at the Chicago Coliseum.

Photo Credit: Chicago Tribune

The Firestone Rubber Company sponsored an educational exhibit on Liberia, the West African nation founded by freed slaves, then the focus of a Black repatriation movement by the American Colonization Society. The fair’s journalism booth showcased the mastheads of 235 Black newspapers. The greatest collection of Negro art ever assembled was on exhibit, as was the Court of Dioramas—33 dioramas the Exposition’s program extolls as “spectacularly beautiful,” and “historically important… illustrating the Negro’s large and valuable contributions to the progress of America and the world.”

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt opened the fair with the press of a button from his Hyde Park, New York home. The fair was the brainchild of James Washington, a Chicago real estate developer. He successfully lobbied the Illinois legislature to appropriate $75,000 for the project. Soon after, Congress matched those funds. Washington hoped the fair would counteract the stereotypes of Black people perpetuated by the 1933 World’s Fair that also took place in Chicago. That fair included a “Darkest Africa” exhibit that offered visitors voyages in canoes “manned by dusky natives.”

Hall of Flags overlooking the American Negro Exposition

The columns in the center surround the Court of Dioramas.

Photo Credit: Chicago Tribune Archive

The fair was hoping to draw two million visitors to the mammoth convention hall to celebrate the contributions of Blacks to America since emancipation 75 years previous. The President was honored to participate, and Chicago Mayor Edward Kelly said, “The nation pays a debt of gratitude to the Negroes today.”

The exposition was dominated by booths showcasing the many New Deal programs and accomplishments. There was a booth for the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC); another for the Federal Works Agency (FWA). “The contribution of the Federal Government to the social and economic progress of the American Negro,” reads the official program, “is the theme of the Exhibit of the Federal Works Agency occupying a commanding space in the Exposition Hall.” The program goes on extolling the virtues of the FWA, citing that the previous year, 300,000 Negro workers were employed on WPA projects and were paid some $15 million in wages.

Mechanical Man

A popular exhibit of the U.S. Dept of Labor

Photo Credit: American Negro Exposition Official Program and Guidebook

The Illinois WPA’s Writers’ Program wrote a book on the fair, Cavalcade of the American Negro, published by the Diamond Jubilee Exposition Authority, it highlighted Black history along with the fair’s extensive offerings, including 33 plaster dioramas, which took center stage at Coliseum.

The dioramas depicted contributions of Africans and others of African descent to world events and culture since Black slaves built the Great Sphinx of Giza. Measuring about 4 by 5 feet, and exquisitely detailed, each diorama was populated with sculpted figures of wood or clay. One diorama depicts the Boston Massacre that ended the life of Crispus Attucks, thought to be the first colonist to die in the American Revolution. Another is of enslaved Africans disembarking a ship onto Virginia soil in 1619. There’s one of dancers celebrating Juneteenth, the oldest nationally celebrated commemoration of the ending of slavery in the United States, dating back to 1865. Another one honors the Black soldiers of World War I.

Pin

American Negro Exposition

Photo Credit: Live Auctioneers

African American artist Charles Dawson designed the 33 dioramas and supervised the 120 Black artisans employed to create them. Twenty of the dioramas are housed at Alabama’s Tuskegee University’s Legacy Museum. Conservators with the Alliance of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) oversaw the restoration of the dioramas, introducing Black students to the field of art conservation.

Dr. Jontyle Robinson, Curator and Assistant Professor at the Legacy Museum notes that those “who organized the 1940 Negro Exposition in Chicago understood the importance of African Americans to American History.” The dioramas reflect that, and are part of that history themselves.

Restoration

Kiera Hammond works on the diorama of the Boston Massacre death of Crispus Attucks.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Winterthur Museum

Other than these twenty dioramas, little else remains of those 1940 Jubilee days. The fate of the13 missing dioramas remains unknown. The Mechanical Man who drew crowds has rusted into oblivion. The remnants of the Chicago Coliseum itself were finally cleared in the early 1990s. Coliseum Park, a dog park across from where the imposing building once stood is the only acknowledgement of the Coliseum in the neighborhood’s history.

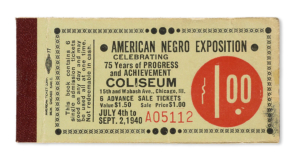

When the exposition closed on September 2, 1940, only 250,000 visitors had taken in the exposition, far fewer than the producers had hoped. In the eyes of many, it was deemed a failure. Yet, the first real Negro World’s Fair still resonates 80 years later. As Dr. Robinson says, “All the police brutality, mass incarceration, lynching, health disparities, red lining, Jim Crow laws and economic discrimination cannot disrupt the truth.”

And the truth is, Black Americans contributions continue and continue.

Ticket Stub

American Negro Exposition celebrating 75 years of progress and achievement.

Photo Credit: Swan Auction Galleries

Diorama Detail

“The Landing of Slaves in Virginia, 1619”

Photo Credit: Julianna Ly

Watch: Preserving Dioramas of African American History (6:40 minutes) CBS Sunday Morning

Jonathan Shipley is a freelance writer based in Atlanta, Georgia. He's written for such publications as the Los Angeles Times, National Parks Magazine, and Seattle Magazine.