Greenwood Massacre

Greenwood was the preeminent black community in the United States in the 1920s

Photo Credit: bswise/ Flickr public domain

The place of African Americans and other people of color in the New Deal still haunts the legacy of President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration. It is well known that FDR had to compromise with powerful Southern Democrats, especially key Committee Chairs and Senators, to get many of his programs through Congress. Moreover, while the New Deal brought about a dramatic increase in federal power, the reality of American federalism meant that control over the implementation of national programs was often in the hands of state and local officials.

As a result, New Deal programs were often infected and undermined by the prevailing racism of American society at the time–-and even by white officials in the administration. For example, when FDR created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in 1933, it was nominally open to all. Yet, in practice, black men were passed over by many recruiters and “African American Corpsmen faced segregation, discrimination and hostility within the CCC and from nearby white communities,” as Olin Cole, Jr. wrote in The African American Experience in the Civilian Conservation Corps.

This was particularly true in the South, where African American Corpsmen in mostly white companies were relegated to cooking and cleaning duties and lived in segregated quarters. In 1935, the national office ordered all companies to be segregated. CCC Director Robert Fechner was a southerner from the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which was notoriously unfriendly to blacks; FDR had appointed him to mollify the AFL over complaints that the Corps was undercutting wages. Unfortunately, similar compromises marked other New Deal programs, like public housing, farm supports and labor legislation.

Yet, key New Dealers resisted the prevailing racism and were able to hire millions of black Americans in work relief programs, install hiring quotas for blacks in federal contracts, dramatically increase the number of black federal employees, and provide targeted housing and loan programs for African Americans. It is important to judge the New Deal in historical perspective and against the virulent racism of the time, and black citizens did so by converting en masse from the Republican to Democratic Party by 1940.

We should recall that the high tide of Jim Crow came in the 1920s, as racist and anti-foreign attitudes intensified following World War One. These were commonly backed up by violence from the Ku Klux Klan and white mobs. In recent news we have been offered a shocking reminder of how bad things were with the dramatic example of the Greenwood Massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

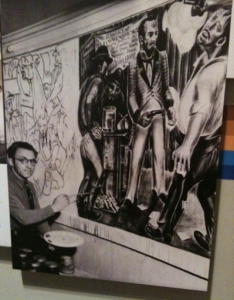

Black Wall Street Ablaze, 1921

The first bombs ever dropped on American soil fell on the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, OK.

Called the Black Wall Street, Greenwood was a very successful African American section of the city. On May 31, 1921, a mob of whites terrorized Greenwood, burning and looting homes and businesses, injuring and killing its citizens. After 18 hours of destruction, 40 square blocks were destroyed, including the public library, hospital, a dozen churches, doctors’ offices, hotels, restaurants and other businesses and more than 1,000 homes. Most of the district’s 12,000 residents were left homeless. Investigations later put the number of dead above 300.

On June 21, 2020, the New York Times published a recounting of the Greenwood Massacre along with arresting, tragic photographs. They resonate with similar images of the death of African Americans at the hands of law enforcement from Louisville to Minneapolis– and even my community of Georgetown, Texas.

In the midst of this, barely three weeks past the 99th anniversary of the Greenwood massacre, the “Make America Great Again” crowd chose Tulsa for a “campaign rally,” not only mocking the memory of the Greenwood victims but endangering the lives of Tulsans today.

We who celebrate the New Deal must not make the mistake of forgetting the racism of the past. We must advocate for a new New Deal that challenges the racial order of today’s America and develops truly inclusive programs that enhance and strengthen the lives of all our citizens.

Watch: “Tulsa race massacre: The painful past of “Black Wall Street”, USA Today (9 minutes)

Milton Jordan, a Living New Deal National Associate for Texas, writes essays, poems and reviews on cultural, historical, political and social issues. He is a participant in the Texas New Deal Symposium, and with George Cooper edited Conflict and Cooperation: Reflections on the New Deal in Texas, Stephen F. Austin University Press, 2019.