FWP Poster

Writers at work. Courtesy, NY City Municipal Archives.

During the Great Depression, improving the nation’s infrastructure wasn’t the New Deal’s only agenda. Economic recovery also meant providing useful relief jobs to creative professionals, leading to the establishment of Federal One, the umbrella organization for the Federal Art, Theatre, Music, and Writers’ Projects.

The Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) employed thousands of out-of-work editors, writers and others, and published hundreds of books in its quest to create a self-portrait of America. It supported writers through hard times and propelled careers, with authors such as Nelson Algren, Ralph Ellison, Saul Levitt, Kenneth Rexroth, Mari Tomasi, May Swenson, Margaret Walker, and Richard Wright among the many authors who were part of this literary legacy. This idealistic program endeavored, through its publications, to celebrate the mosaic of racial, ethnic and cultural identities in America. It also, unfortunately, attracted the attention of conservatives, anti-New Dealers and the first iteration of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), leading to the FWP’s shutdown.

American Guide

The FWP published travel guides to 48 states and some regions and cities. Photo by Addie Borchert.

After Congress defunded the FWP in 1939, it was soon nearly erased from the public mind. A host of books, starting with Jerre Mangione’s 1972 book, The Dream and the Deal, resurrected interest in the FWP, helping to re-establish the importance of the Project.

Scott Borchert’s new book, Republic of Detours: How the New Deal Paid Broke Writers to Rediscover America, (2021 Farrar, Straus and Giroux) adds an important voice to understanding this seminal federal effort, particularly now that legislation has been introduced to establish a 21st century FWP.

Borchert’s well-researched history of the Project is offered alongside a historical backdrop. The American literary scene converges with cultural and political themes, stretching from the aftermath of the Civil War through the 1930s. The narrative and inviting writing style are welcoming to both FWP scholars and readers new to the Project.

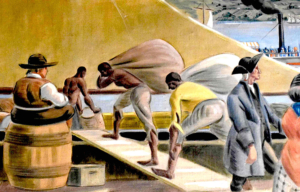

Gathering of Nuggets

The frontpiece of the FWP’s 1939 book, “Idaho Lore”. Courtesy, LOC.

Borchert’ interest in the FWP began with the discovery of a treasure trove of American Guide books in his great-uncle’s attic. The American Guide series, the centerpiece of the FWP’s accomplishments, spanned every one of the then-48 states, as well as Puerto Rico, Washington, D.C. and dozens of cities and regions. Each guide included not only travel tours, but also essays on local folklore, history and geography.

Borchert’s telling of the FWP encompasses everything that made the agency special: the oral history/slave narratives collected by FWP workers; aspiring, soon-to-be famous writers; the evolving American Guide book series; segregation and racism in the Southern States; the “secret” creative writing unit approved by FWP director Henry Alsberg—and much more.

Temple Herndon Dunham, Age 103

From “Born in Slavery, Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project.” Courtesy, LOC Slave Narrative Collection.

Borchert examines previously unexplored aspects of the Project, including important but lesser known editors and writers like Vardis Fisher, the director of the Idaho Writers’ Project. Fisher, a novelist who grew up on a homestead, almost singlehandedly wrote his state’s guide, the first to be published. Readers also learn about Katharine Kellock, the FWPs highest-ranking woman, a powerhouse who helped devise the tour sections of the guide books. Borchert also brings us the story of writer Sherwood Anderson’s little-known involvement in the New Deal, as he traveled the nation to write for the FDR-endorsed magazine, Today, reporting on the impacts of Roosevelt’s new policies.

Rep. Martin Dies with Hollywood studio executives, 1939

Dies head a House Special Committee to combat un-American ideologies. Photo Credit: National Archives & Records Administration. Courtesy, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives.

No book on the FWP is complete without the battle played out in newspapers of the day, between Congressman Martin Dies, who chaired HUAC, and FWP’s beleaguered director Henry Alsberg, who struggled to save the Project and its writers from reactionary elements. Borchert also highlights the cultural and historical events that influenced HUAC and triggered its creation.

The legacy of the FWP is often wrapped around its famous writers and its work relief programs. Borchert points to yet another legacy.

Henry Alsberg

The founding director of the FWP testifying at HUAC hearing, 1938. Courtesy, LOC.

“The FWP, utterly and explicitly, was anti-fascist by design,” Borchert writes. He reminds us that the FWP was created while fascism was taking hold abroad and domestic groups like the Ku Klux Klan tried to worm its way into American society. “This was the backdrop against which the FWP was initiated, the fascist upsurge that it sought— through the American Guides and other efforts—to oppose.”

Susan Rubenstein DeMasi is the author of the 2016 biography, Henry Alsberg: The Driving Force of the New Deal Federal Writers’ Project. She is a visiting scholar in this summer’s National Endowment for the Humanities program, “The New Deal Era’s Federal Writers’ Project,” as well as a contributor to an upcoming book on the literary legacy of the FWP, edited by Sara Rutkowski, for the University of Massachusetts Press.

[email protected]

has joined the

has joined the