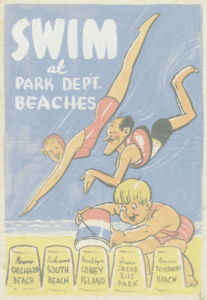

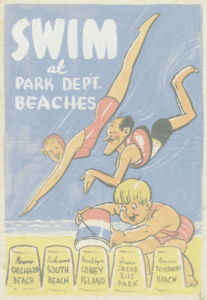

“Swim” original art for subway, 1937. Tempura water color on tissue paper; artist unknown

A life-long swimmer, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses vastly expanded access to aquatic facilities for New Yorkers. In 1936, he opened ten new swimming pools and during his long tenure he built and improved public beaches throughout the city.

Photo Credit: Department of Parks General Files, 1937. NYC Municipal Archives

Located in one of the City’s most beautiful Beaux-Arts buildings, the landmark Surrogate’s Court at 31 Chambers Street in Manhattan’s Civic Center, are the Municipal Archives and Municipal Library. Here the City preserves and makes available to the public the historical and contemporary records of New York City’s municipal government.

To the eternal benefit of generations of historians and researchers, the Archives hold two extensive collections essential for exploring the New Deal in New York City.

Documenting the New Deal in the city is largely a tale of two remarkable New Yorkers, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and ‘master builder’ Robert Moses. Records in the Archives of their influence and impact on the city total more than 1,500 cubic feet.

Fiorello LaGuardia represented a Manhattan district in the U.S. Congress from 1916 – 1932. Elected New York’s mayor in 1933, he served three terms, 1934 – 1945. When Works Progress Administration funding became available in 1935, LaGuardia persuaded FDR to release billions of dollars for construction projects. It was a partnership that would forever change the city. New York would receive more federal funds than any other city in the nation and employed more than 700,000 people through the Depression years. They built or renovated schools, bridges, parks, hospitals, highways, airports, stadiums, swimming pools, beaches, hospitals, piers, sewers, libraries, courthouses, firehouses, markets, and housing projects throughout the five boroughs.

Sara Delano Roosevelt Park, March 6, 1934

Several blocks of tenements in Manhattan’s lower East Side, from Houston to Rivington Streets, were razed for construction of the Sara Delano Roosevelt Park.

Photo Credit: Department of Parks Collection, DPR_0046. NYC Municipal Archives

LaGuardia’s correspondence and other materials from his public service are housed at the Municipal Archives. Of particular interest to New Deal historians are the subject files. These include records pertaining to the Civilian Conservation Corps, housing projects, public works, and LaGuardia’s extensive correspondence with officials in Washington D.C.—totaling 365,000 documents.

LaGuardia’s records have been available at the Municipal Archives since its founding in 1952. The Robert Moses collection is a more recent addition.

In 1984, city archivists visited a Department of Parks and Recreation storage facility at the Manhattan Boat Basin where they discovered 800 cubic feet of material—about 400,000 items—from 1934 through the 1970s, comprising a nearly complete record of the WPA-funded projects during Moses’s long reign as a New York power broker. Moses served as Commissioner of the Department of Parks from 1934 through 1960, while he also held at least a dozen city and state positions. The records found at the Boat Basin are in remarkably good condition, consisting of carbons or originals of Moses’s correspondence, memoranda, transcripts, reports, contracts, news clippings, maps, blueprints, plans, printed materials, press releases, invitations, and photographs.

Harry Hopkins, who headed the WPA, extended the program to include white-collar professionals in art, theater, music and writing programs, insisting that “They have to eat like other people.” Records at the Archives include photographs, manuscripts and research files of the NYC Unit of the Federal Writers’ Project, which produced books and pamphlets ranging from the popular New York Panorama and New York City Guide, to How We Keep our City Clean, History of WNYC—(the city’s premier radio station), and Architecture of New York.

Astoria Pool, Queens, August 20, 1936.

Opened July 2, 1936, Astoria Pool is the largest of the eleven pools Moses built with funding from the Works Progress Administration program.

Photo Credit: Department of Parks Collection, DPR_10776-2. NYC Municipal Archives

Pelham Bay Park, October 22, 1941.

No detail was too small or building too insignificant for Moses and his talented team of architects as illustrated by the handsome design of this comfort station.

Photo Credit: Department of Parks Collection, DPR_20920. NYC Municipal Archives

New York City’s archival program dates back more than a century to establishment of the Municipal Reference Library in 1913. Under the leadership of long-time Library Director Rebecca Rankin (1920-1952), the Library began acquiring original historical documents from City municipal offices. During the 1930s, with the backing of Mayor LaGuardia, Rankin developed a municipal records management and archives program, modeled on the federal system. Eventually, the program acquired a building and on June 30, 1952, the day Rankin retired, the Municipal Archives and Records Center officially opened. In 1977, the Municipal Archives and Municipal Library were incorporated into the newly established Department of Records & Information Services.

Other highlights to be found at the Archive’s wide-ranging records are photographs of every house and building in New York City dating from 1940 and 1985, two centuries of mayoral papers, more than 1,500 drawings of Central Park, and the architectural plans for construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. The Archives regularly curates exhibitions that are open to the public. For information about access to collections, researchers are encouraged to email inquiries to [email protected].

Henry Hudson Parkway, ca. 1937

Originally designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Riverside Park was expanded and augmented with federal funds allocated for the highway. The Boat Basin at 79th Street was incorporated into the highway interchange at 79th Street.

Photo Credit: Municipal Archives Collection, MAC_0031. NYC Municipal Archives

Playground, Fifth Avenue and 130th Street, Manhattan, ca. 1937

One of the thousands of new playgrounds throughout the city built or renovated with WPA funds.

Photo Credit: Fiorello LaGuardia Collection, FHL_0117. NYC Municipal Archives.

Kenneth Cobb is Assistant Commissioner in the Department of Records & Information Services. He joined the Municipal Archives in 1978 and served as Director from 1990 through 2004.