Learn to Swim, Poster by John Wagner

NYC WPA Art Project, 1940

Photo Credit: Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

New Deal New York, a map recently produced by the Living New Deal is not just any map. This one tells a story—the triumph of liberal democracy in the 1930s.

New Deal New York depicts 1,000 sites, showing that the New Deal legacy lives on in all of the city’s five boroughs in the form of artworks, schools, parks, recreation centers, and major public buildings. This infrastructure, the editors of Fortune pointed out, was “a conspicuous example of the social dividend,” promised by the New Deal.

New Yorkers have three politicians to thank for this: President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. The city won one-seventh of all expenditures made by the WPA in 1935 and 1936—so much that New York City was known as the fifty-first state. Moses spent some $113 million—nearly $2 billion in today’s dollars— on parks and recreation alone in the New Deal’s first two years.

Colonial Park Pool and Bathhouse, 1936

Jackie Robinson Park, Manhattan

Photo Credit: Courtesy NYC Parks

The construction program faced extraordinary challenges—the need to build fast (no one knew how long Congress would subsidize the public works program); the federal mandate that inexpensive materials be used; and that the unemployed be hired as construction workers, not necessarily skilled laborers.

Writer Lewis Mumford, noted for his study of cities and urban architecture, recognized all that was achieved when he invented the capacious term, “sound vernacular modern architecture,” in praise of the New Deal’s results in New York City. He alluded to the freedom of expression that New Dealers insisted is part and parcel of a democracy. Authoritarian regimes may have mandated specific architectural styles, but not the United States, where pluralism was preferred.

Astoria Pool, 1936

State-of-the-art Olympic-size pool in Queens, NY

Photo Credit: Courtesy NYC Parks

In the ensuing building frenzy New Dealers made New York City a better place, a safer place, and a healthier place to live, especially for children. Gyms, playgrounds, parks, ball fields, basketball and tennis courts, and running tracks were built throughout the city. Eleven new public swimming pools and bathhouses were immediately commissioned at a cost of about $1 million each, and several others were added subsequently.

Girls’ Line at Betsy Head Recreation Center, 1939

Brooklyn, NY

Photo Credit: Samuel Gottscho, Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Gottscho-Schleisner Collection

Each week the pools opened, one by one, during the hot summer of 1936, and thousands of New Yorkers attended the spectacular opening ceremonies. By Labor Day, more than 1.6 million people had used new facilities. Most were children—working-class boys who had previously skinny-dipped in polluted water surrounding the city (during the launch of New Deal New York, the historian, Bill Leuchtenberg, revealed that he was one of them), and working-class girls who had had no other place to swim.

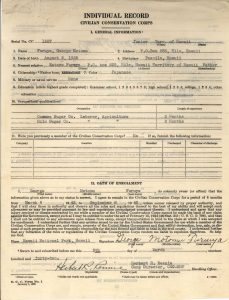

A wonderful photograph of two children at Red Hook Recreation Center is featured on New Deal New York map. The kids, who are posing for the photographer, Arthur Rothstein (he worked for another New Deal program, the Farm Security Administration) are standing on broad ledges, called scum gutters, designed to keep water clean and swimmers healthy. Kids hung on to the ledges as they practiced kicking, breathing, and stroking. Thanks to funding from the WPA, the Department of Parks ran a “Learn-to-Swim Program,” that benefitted all children, regardless of race, ethnicity, or gender.

Children at Red Hook Pool, 1936

Brooklyn, NY

Photo Credit: Arthur Rothstein, Courtesy Library of Congress

The WPA also paid for the poster that promoted the program (including the artist who designed it). It is one that some historians insist depicts the color line that segregated pools under the Moses regime. I’ve argued otherwise; while the color line ran through pools and parks that were built in the city’s segregated neighborhoods, it didn’t run through all of them. New Yorkers, prime among them children, tested entrenched racism during the New Deal and did defeat it in this city

As radio host Sarah Fisko said recently on NPR, “when you can’t see ahead, you look back.” New Deal New York helps us to remember what New Dealers accomplished in New York City in the face of the gravest challenges to our democracy, and to grasp what we can do—what we must do—as we face them once again.

Marta Gutman teaches architectural and urban history at the City College of New York and the CUNY Graduate Center. Her research focuses on public architecture for city children.