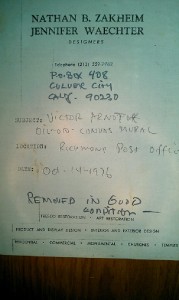

Brass Plaque

One of four different brass plaques at the Monterey County Courthouse, this one representing agriculture.

Photo Credit: Peter Hiller

It is rare for any artist to support a family solely through artistic prowess, and rarer still during the Great Depression. Joseph Jacinto “Jo” Mora (1876-1947) was such an artist. Mora used his wits as well as his expansive creative abilities to keep food on the table.

An illustrator, writer, cartographer, architect, photographer, sculptor, and painter, Mora’s extensive talent spanned several decades including during the New Deal era. Born in Uruguay, the son of a classical sculptor, Jo Mora grew up and attended school in neighborhoods in New Jersey, New York, and Boston. After attending art school, training with his father and honing his artistic skills as an illustrator for Boston area newspapers and book publishers, Jo followed his heart and traveled west.

Justice

Mora’s depiction of Justice as seen on the east side of the Monterey County Courthouse.

Photo Credit: Peter Hiller

In 1903, Mora rode the train to California on his own to work as a cowboy at the Donahue Ranch in the Santa Ynez Valley where he would learn the ways of the Californio vaqueros and take time to draw, paint, and photograph the California Missions along the El Camino Real. He continued back to Arizona, living with the Hopi and Navajo, learning their languages and documenting their daily lives and sacred ceremonies in drawings, paintings, and photographs.

After two and a half years in Arizona, Mora tore himself away from a life he loved, married, and settled in the San Francisco Bay Area, working full time as an artist. He painted murals, continued to write and illustrate children’s books as he had done in Boston, as well as create heroic sculptures and decorative elements on numerous buildings in California. A rock and bronze statue of Miguel de Cervantes in Golden Gate Park was one of several sculptural commissions during this period of Mora’s life.

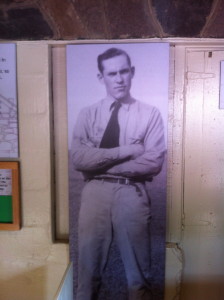

Mora and Stanton

Jo Mora (left) and Robert Stanton with one of the column caps in Mora’s studio.

Photo Credit: Lewis Josselyn from the Jo Mora Trust

The Mora family, his wife Grace, son Jo Jr., and daughter Patti moved to Carmel-by-the-Sea, as Mora was commissioned to create a monumental cenotaph in honor of Father Junipero Serra for the Carmel Mission. The family would quickly become ensconced in the community, living first in Carmel and then moving to nearby Pebble Beach.

In 1937, in collaboration with architect Robert A. Stanton, a family friend and neighbor, Mora undertook two enormous projects under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration. Stanton was charged with designing a new courthouse for Monterey County and Jo was commissioned by the WPA to add artistic elements to the building. Stanton’s monolithic design gave Mora many options for his part of the project. He drew on his love of California and the Southwest to produce ornamental pieces tht reflected the history, commerce, and people of California—Native American, Spanish, Mexican, and Anglo.

Jo Mora in Studio

Mora posing with three of the bas-relief panels for the King City High School Auditorium, King City, CA. Source

Photo Credit: Lewis Josselyn from the Jo Mora Trust

Mora created bas-reliefs capping the four tall columns in the west interior courtyard of the building; five travertine bas-relief panels above the west entrance; twenty three different 3-dimensional concrete heads of persons both real and archetypal; four different brass plaques on the building’s exterior doors ant the interior elevator doors; a bas-relief figure depicting Justice on the east side of the building, and a sculpted center column in a reflecting pool in the central courtyard of the building.

The success of the courthouse project would led to another Stanton-Mora undertaking in the southern end of Monterey County, the King City High School Auditorium, where Stanton designed the building and Mora, again working for the WPA, created bas-relief style figures for the column caps on the building’s sides, as well as a spectacular 9-panel bas-relief on the front. Mora depicted the performing and visual arts, along with images inspired by California’s many cultures.

Monterey Courthouse

In order for court to stay in session during the construction of the new building, Stanton’s design was to build around the old courthouse and then remove the old building, board by board, through the open columns. Mora added many decorative elements to the completed building. Source

Photo Credit: Photograph from the collection of the Pebble Beach Company.

Both of these striking buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places and are still in use today.

Peter Hiller is the collection curator for Jo Mora Trust.