- Home

- /

- Racism and Beyond: A...

- /

- A New Deal For...

- /

- Jewish Americans and Refugees

Jewish Americans and Refugees

Scroll down for our photo gallery below!

Anti-Semitism was an age-old scourge of Europe that carried over to the United States, despite the greater religious tolerance that developed through the Philadelphia model of the mid-Atlantic colonies and was written into the Bill of Rights of the U.S. Constitution. Pogroms and other mass attacks on Jews were unknown in America, but anti-Semitic prejudices simmered among many Christians, Protestant and Catholic alike. Nevertheless, the country allowed entry to millions of Jewish refugees from Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

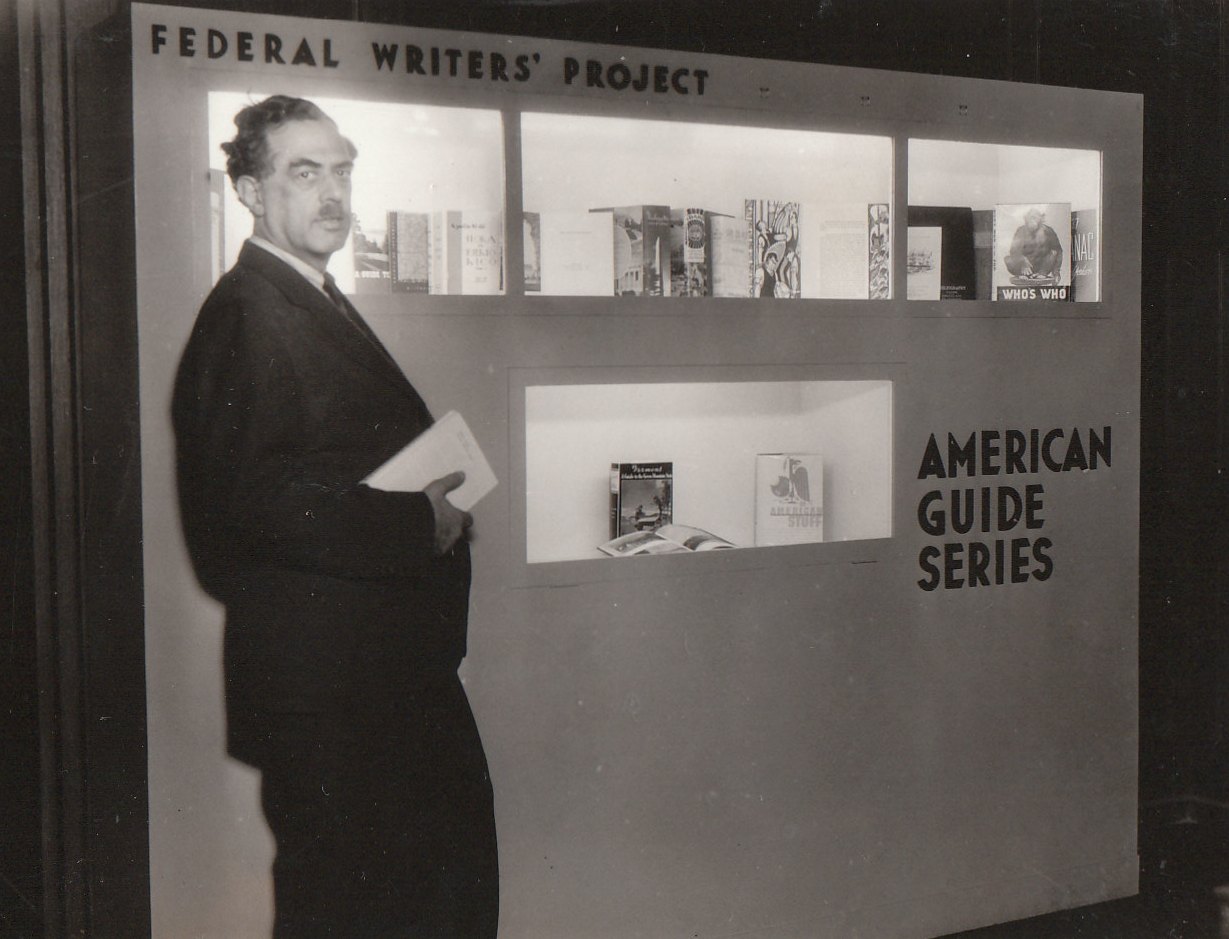

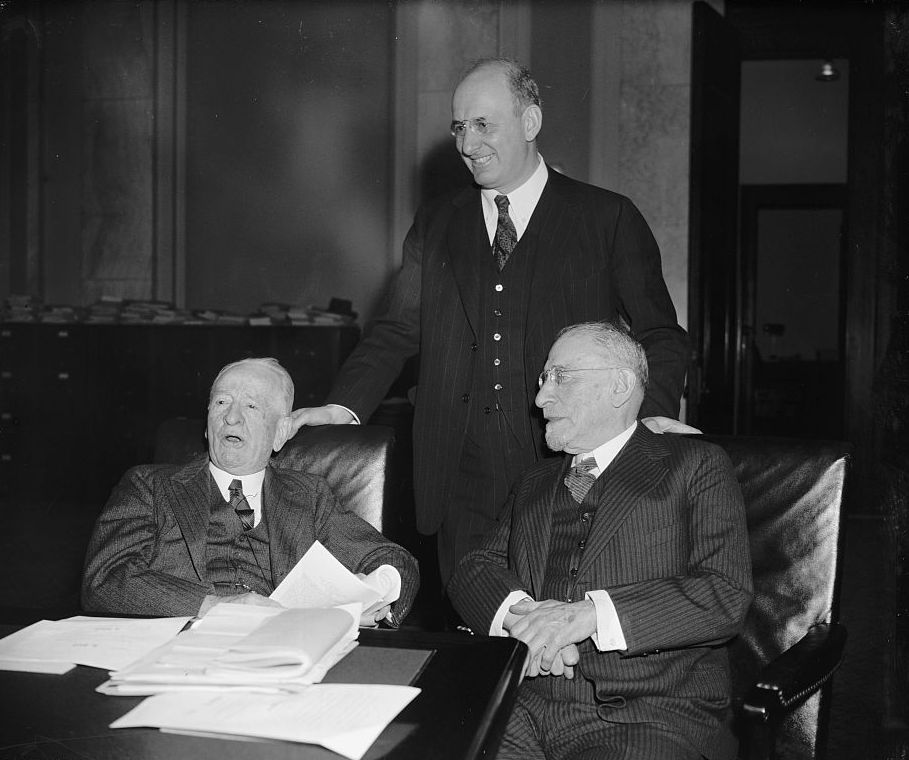

As the Jewish population swelled and Jews found a secure home in this country, they began to participate more in American politics, education and culture. Some, like Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, rose to important positions in national life during the Progressive Era. Carrying that legacy forward, President Franklin Roosevelt welcomed Jewish Americans into government and into high positions in his administration [1].

As a result, FDR and the New Deal were denounced by anti-Semitic figures like Father Coughlin and fascist organizations such as the “Silver Shirts” (or Silver Legion of America), which warned Americans about a Jewish infiltration of Christian government. Their founder, William Dudley Pelley, referred to FDR as that “Dutch Jew Franklin Rosenfelt” [2]. Meanwhile, the “American Vigilant Intelligence Federation… maintained a continuous criticism of Roosevelt, the New Deal, and Jews” [3] and the “Knights of the White Camelia” called the New Deal the “Jew Deal” [4].

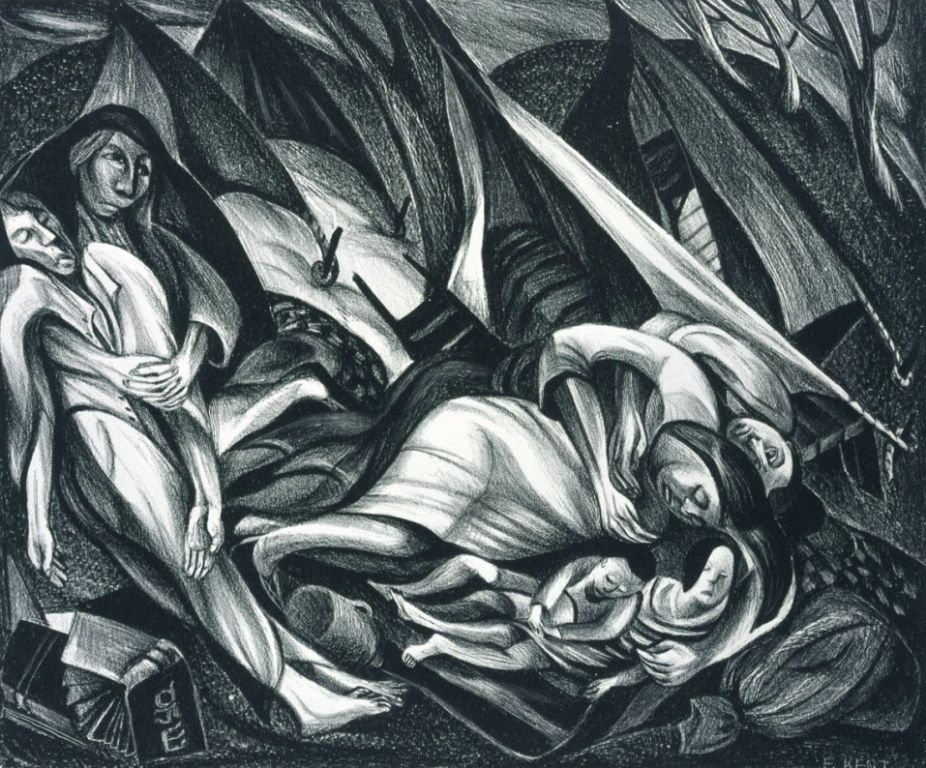

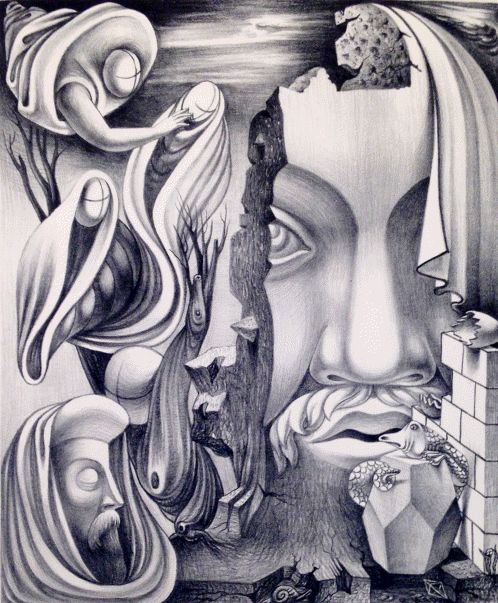

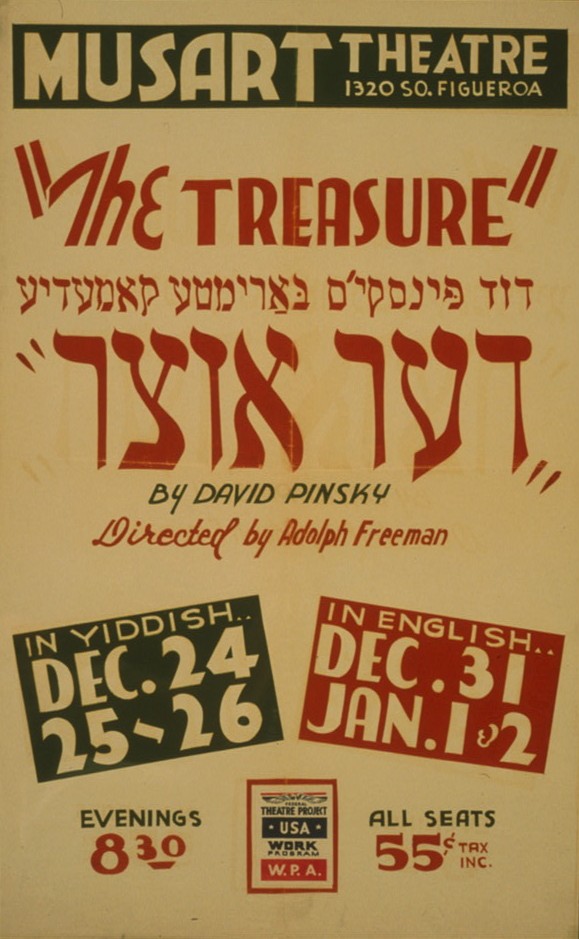

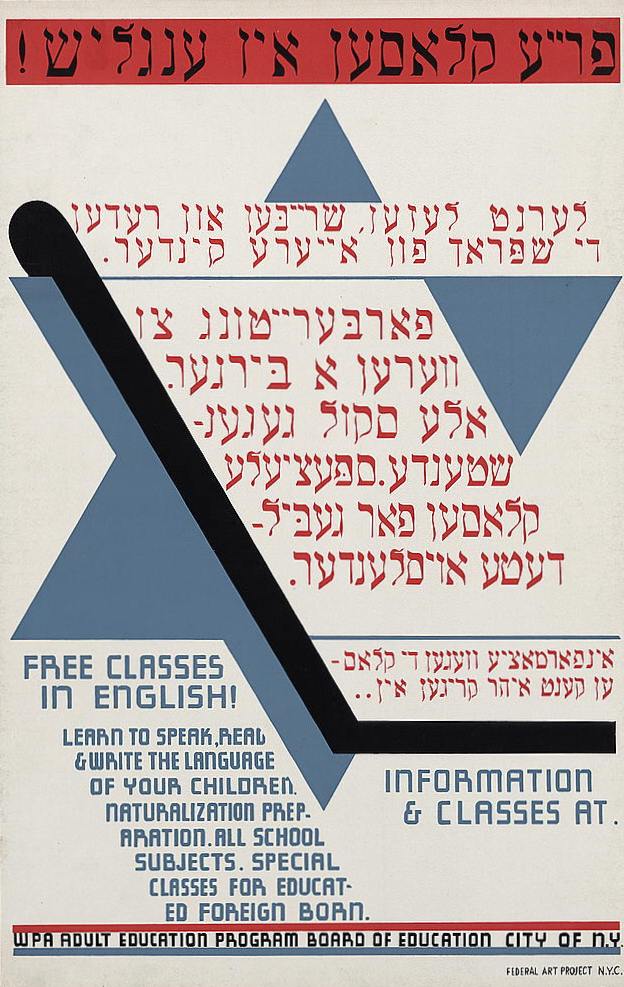

The coming of the Nazi regime in Germany and rising tide of anti-Semitism across Europe in the 1930s disturbed many Americans of good conscience, but did not lead to widespread public condemnation nor to a groundswell of support for Jewish refugees escaping the rising persecutions of the Nazis and reactionaries in the Old World. Most New Dealers were welcoming of Jewish refugees, however. Eleanor Roosevelt advocated for increased immigration, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes proposed settling Jewish refugees in the Virgin Islands or Alaska, and WPA Theatre Director Hallie Flanagan eagerly supported Yiddish theatre productions, including It Can’t Happen Here [5].

President Roosevelt was deeply concerned about the plight of the Jewish people. As Secretary of Labor France Perkins later wrote:

“The aggression against the Jewish people in Germany filled him with horror. They seemed to him almost unbelievable… Roosevelt moved to make it possible to bring over people who had relatives here to guarantee their support. He endorsed a program to bring over orphaned and handicapped children who had no relatives [to be supported by] the Council of Jewish Women and also by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid and Shelter Society. This move was not too popular in some quarters…” [6].

Yet Roosevelt also hesitated to protect Jewish refugees and welcome Jewish immigrants. A glaring example was allowing the Jewish refugee ship, the St. Louis, to be turned away from U.S. ports in 1939. He has also been criticized for not using the bully pulpit of the presidency to support protective legislation [7]. Ultimately, FDR considered that the best way to help the Jewish people was to focus on the defeat of Germany.

No doubt, Roosevelt’s hesitancy was certainly influenced by the state of American opinion, to which he was always finely attuned. He understood the deeply embedded racism and anti-Semitism of the American public, and polls of the late 1930s showed that both Protestants and Catholics were overwhelmingly against accepting Jewish refugees into the country [8]. As the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. notes: “Widespread racial prejudice among Americans… played a part in the failure to admit more refugees. In the midst of the Great Depression, many Americans also believed that refugees would compete with them for jobs and overburden social programs set up to assist the needy” [9].

Unfortunately, failure to act in key situations has, in recent times, been used to paint Roosevelt as apathetic to the plight of the Jews, or even anti-Semitic. This is a clear perversion of history, as Laurence Zuckerman has observed:

“In recent years, the distorted view of FDR has been promoted by a small group of Israel supporters who cherry-pick the historical record to portray his handling of the Holocaust in the most negative light possible. These scholar-activists deploy similar sleight of hand to paint a picture of most American Jews as having been disengaged and apathetic about the fate of their European counterparts at the hands of the Nazis, and to cast as heroes a small group of right-wing Zionists who mounted an aggressive public relations campaign to pressure Roosevelt to act. In this narrative, the complexities of history are erased…” [10].

Roosevelt finally took decisive action in creating the War Refugee Board (WRB) in 1944 to carry out the policy of rescuing “victims of enemy oppression who are in imminent danger of death and otherwise to afford such victims all possible relief and assistance consistent with the successful prosecution of the war” [11]. The WRB facilitated the rescue of Jews through various methods, including bribery, false identification papers, transportation planning, funding for hiding places, and coordination with resistance groups [12]. FDR did not live to see the full revelations of the Nazi death camps nor the benefits of the WRB’s efforts to bring tens of thousands of Jewish refugees to the United States.

Sources: (1) See, e.g., “Discusses Role Taken by Jews in the New Deal,” The News-Palladium (Benton Harbor, Michigan), April 6, 1935 (about a discussion on Henry Morgenthau, Bernard Baruch “and other [Jewish] leaders”). (2) James S. Olson (ed.), Historical Dictionary of the New Deal: From Inauguration to Preparation for War, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985, p. 453. (3) Ibid., at p. 22. (4) Ibid., at p. 284. (5) See note 7 below; and T.H. Watkins, Righteous Pilgrim: The Life and Times of Harold L. Ickes, 1874-1952, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1990, pp. 672-675; and generally, Hallie Flanagan, Arena, New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1940. (6) Frances Perkins, The Roosevelt I Knew, New York: The Viking Press, 1946, p. 349. (7) “Franklin Delano Roosevelt,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (accessed February 9, 2018). (8) See, e.g., The Roosevelts: An Intimate History, a 2014 documentary film by Ken Burns and PBS. (9) “Emigration and the Evian Conference,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (accessed February 9, 2018). (10) Laurence Zuckerman, “FDR’s Jewish Problem,” The Nation, July 17, 2013. (11) “Executive Order 9417 Establishing the War Refugee Board. January 22, 1944,” The American Presidency Project, University of California Santa Barbara (accessed February 9, 2018). (12) See, generally, War Refugee Board, Final Summary Report of the Executive Director, September 15, 1945 (available to view or download at Hathitrust).