Roosevelt Inauguration 1933

Chief Justice Charles Hughes administers the oath of office to FDR in 1933. Source

As the first election returns reached his family estate in Hyde Park, New York, on a November night in 1936, Franklin Delano Roosevelt leaned back in his wheelchair, his signature cigarette holder at a cocky angle, blew a smoke ring and cried “Wow!” He had been swept into a second term with the largest popular vote in history at the time.

The outpouring of ballots for the Democratic ticket reflected the enormous admiration for what FDR had achieved in his first term. When he was inaugurated in March 1933 one-third of the workforce was jobless, industry all but paralyzed, farmers desperate, and most of the banks shut down. In his first 100 days he had put through a series of measures that lifted the nation’s spirits.

In 1933 workers and businessmen marched in spectacular parades to demonstrate their support for the National Recovery Administration (NRA) Roosevelt’s agency for industrial mobilization. Farmers were grateful for subsidies dispensed by the newly created Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). Over the ensuing three years, the cavalcade of alphabet agencies had continued: SEC, REA, CCC, NYA, the WPA, and more. A second burst of legislation in 1935 brought the Social Security Act.

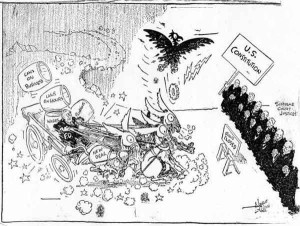

During the 1936 campaign the president’s motorcade was mobbed by well- wishers wherever he traveled. His landslide victory signified the people’s verdict on the New Deal. The jubilation was tempered, however, by an inescapable fear—that the U.S. Supreme Court might continue to undo Roosevelt’s accomplishments.

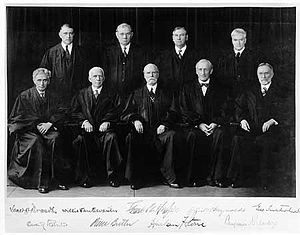

From the outset of his presidency, FDR had known that four of the justices—Pierce Butler, James McReynolds, George Sutherland and Willis Van Devanter—would vote to invalidate almost all of the New Deal. They were referred to in the press as “the Four Horsemen,” after the allegorical figures of the Apocalypse associated with death and destruction.

In the spring of 1935, a fifth justice, Hoover-appointee Owen Roberts—at 60 the youngest man on the Supreme Court—began casting his swing vote with them to create a conservative majority. During the next year, these five judges, occasionally in concert with others— especially Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes—struck down more significant acts of Congress than at any other time in the nation’s history, before or since.

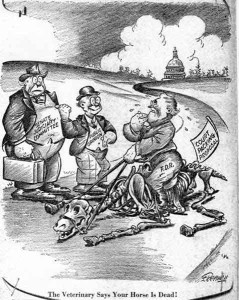

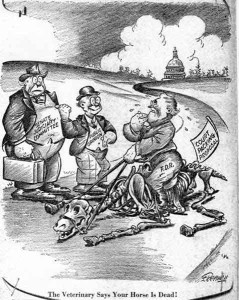

In May 1935 it shot down the NRA, the industrial recovery program. Seven months later, it annihilated FDR’s farm program by determining that the AAA was unconstitutional. In another case, the court construed the Interstate Commerce clause so narrowly that not even so vast an industry as coal mining fell within the government’s power to regulate.

In May 1935 it shot down the NRA, the industrial recovery program. Seven months later, it annihilated FDR’s farm program by determining that the AAA was unconstitutional. In another case, the court construed the Interstate Commerce clause so narrowly that not even so vast an industry as coal mining fell within the government’s power to regulate.

These decisions drew biting criticism from inside and outside the court. Justice Harlan Fiske Stone, a Republican who had been Calvin Coolidge’s attorney general, denounced Roberts’ opinion striking down the farm law. Many farmers were incensed. On the night following Roberts’ opinion, a passerby in Ames, Iowa, discovered life-size effigies of the six majority opinion justices hanged by the side of a road.

Fury intensified when in June 1936 the court, by 5 to 4, struck down a New York state law providing a minimum wage for women and child workers. The ruling persuaded Roosevelt that he had to act to curb the court. It had already torpedoed the two principal recovery projects of his first term. It would soon rule on the Social Security Act and the National Labor Relations Act (the Wagner Act), regarded by the administration as a factory workers’ Magna Carta.

Fury intensified when in June 1936 the court, by 5 to 4, struck down a New York state law providing a minimum wage for women and child workers. The ruling persuaded Roosevelt that he had to act to curb the court. It had already torpedoed the two principal recovery projects of his first term. It would soon rule on the Social Security Act and the National Labor Relations Act (the Wagner Act), regarded by the administration as a factory workers’ Magna Carta.

The president recognized, however, that he must tread carefully, for despite widespread disgruntlement, most Americans believed the Supreme Court sacrosanct. He charged Attorney General Homer Cummings to come up with a plan to ensure a more favorable response to the New Deal from the court. These explorations proceeded stealthily; the president never mentioned the court during his campaign for reelection.

In the days following the 1936 election, FDR and Cummings put the final touches on an audacious plan to reconfigure the court, capitalizing on the public’s concern about the ages of the justices. At the time it was the most elderly court in the nation’s history, with six of the justices 70 or older. Neither Congress nor the Supreme Court itself had any inkling of what was afoot.

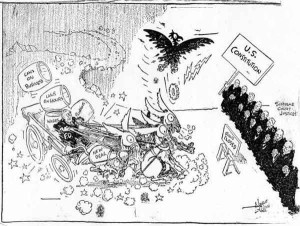

On February 5, 1937, FDR unleashed a thunderbolt. He asked Congress to empower him to appoint an additional justice for any member of the court over age 70 who did not retire. He sought to name as many as six additional Supreme Court justices as well as up to 44 judges to the lower federal courts, contending that a shortage of judges had resulted in delays to litigants because federal court dockets had become overburdened. It touched off the greatest struggle in our history among the three branches of government.

The controversy dominated newspaper headlines, radio broadcasts, and newsreels, and spurred countless rallies in towns coast to coast. Members of Congress were so deluged by mail that they could not read most of it, let alone respond.

Although the country divided evenly on the issue, the opposition drew far more attention. Still, pundits expected the legislation to be enacted—a prospect that drove opponents to a fury of activity: protest meetings, bar association resolutions, and thousands of letters to editors. Roosevelt’s foes accused him of mimicking Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin. His supporters responded that at a time when democracy was under fire, it was vital to show the world that representative government was not hobbled by judges.

Roosevelt’s adversaries advanced their case in hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee. The most dramatic testimony came from an unexpected participant: the Chief Justice of the United States. In a letter read aloud at the hearing, Charles Evans Hughes blew gaping holes in the president’s claim that the court was behind in its schedule and that additional (and younger) justices would improve its performance.

Almost no legislator really liked FDR’s scheme, but most Democratic senators thought they could not justify to their constituents defying the immensely popular president even though there was every reason to suppose it would soon strike down cherished new laws, including the Social Security Act. Most observers expected Roosevelt’s proposal to be adopted. The court, however, would spring some surprises of its own.

Almost no legislator really liked FDR’s scheme, but most Democratic senators thought they could not justify to their constituents defying the immensely popular president even though there was every reason to suppose it would soon strike down cherished new laws, including the Social Security Act. Most observers expected Roosevelt’s proposal to be adopted. The court, however, would spring some surprises of its own.

On March 29, by 5 to 4, in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, it validated a minimum wage law from the state of Washington, a statute essentially no different from the New York state act it had struck down only months before. Two weeks later, the court sustained the National Labor Relations Act. On May 24, the same court that in 1935 had declared that Congress, in enacting a pension law had exceeded its powers, found the Social Security statute constitutional.

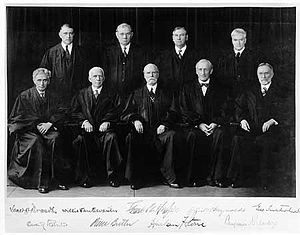

Supreme Court 1932

The Hughes Court, 1932–1937. Front row: Justices Brandeis and Van Devanter, Chief Justice Hughes, and Justices McReynolds and Sutherland. Back row: Justices Roberts, Butler, Stone, and Cardozo.

This set of decisions came about because one justice, Owen Roberts, had switched his vote. Scholars have speculated as to why, but the pressure exerted by a popular president’s court-packing bill may very likely have been influential. Never again would the court strike down a New Deal law.

Ultimately, the Senate buried FDR’s bill. Why continue the fight after the court was rendering the kinds of decisions the president had been hoping for? The nasty fight over court packing turned out better than might have been expected. The end of the bill meant that the institutional integrity of the Supreme Court had been preserved—its size had not been manipulated for political or ideological ends. On the other hand, Roosevelt claimed that though he had lost the battle, he had won the war. He had preserved his New Deal.

William Leuchtenburg is a member of the Living New Deal Advisory Board. He is widely regarded as the dean of New Deal historians. His books include The Perils of Prosperity, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, and The FDR Years: Roosevelt and His Legacy. He taught history at Columbia University for thirty years. Today he is William Rand Kenan Jr. Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina. He served as an advisor to Ken Burns on the PBS series “The Roosevelts.”

William Leuchtenburg is a member of the Living New Deal Advisory Board. He is widely regarded as the dean of New Deal historians. His books include The Perils of Prosperity, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, and The FDR Years: Roosevelt and His Legacy. He taught history at Columbia University for thirty years. Today he is William Rand Kenan Jr. Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina. He served as an advisor to Ken Burns on the PBS series “The Roosevelts.” Email

A version of Dr. Leuchtenburg’s article appeared in Smithsonian Magazine in May 2005.