Among the various New Deal programs to help displaced farmers and the urban poor was the Resettlement Administration’s plan to construct new communities called Greenbelt Towns. These towns were a utopian model of modern living envisioned by RA administrator Rexford G. Tugwell who served on FDR’s “brain trust.”

I became interested in Tugwell’s egalitarian ideas for fostering community through the physical and social aspects of town planning, encompassing affordable housing, communal activities, natural landscaping, and cooperatively owned businesses. It was a new concept for Americans, but not for Tugwell, who was influenced by the work of Sir Ebenezer Howard, an urban reformer whose work transformed the landscape of British industrial communities in the early 20th Century. In order to provide relief from the overcrowded slums of London, Howard proposed creating Garden Cities–new communities that would combine the best features of both town and country, namely the social and economic advantages of living in a community with fresh air and green spaces.

I made multiple trips to photograph the three New Deal Greenbelt Towns–Greenbelt, Maryland; Greenhills, Ohio; and Greendale, Wisconsin. I had learned about the towns through my research on the Garden City, having been inspired by the design and community I found at Julia C. Lathrop Homes, a public housing complex built by the Public Works Administration in 1938. Chicago’s Lathrop Homes had been built with Garden City principles in mind. The New Deal Greenbelt Towns were sited on the suburban frontier outside metropolitan centers.

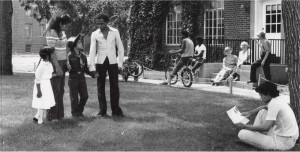

Photographing the Greenbelt Towns, I was struck by the beauty and modesty of the architecture and surrounding natural landscapes, as well as the generosity of the residents. Wandering the parks and converging paths, I reflected upon Tugwell’s bold attempt to introduce a new American way of life based on cooperation instead of unrestrained competition. I was impressed at how connected residents felt to their own town, and to their sibling model communities borne out of the Great Depression. As these towns celebrate their 80th anniversaries in 2017 and 2018, I view them as vital communities to be protected and celebrated.

I am excited to share my photographs of the towns in my new book, New Deal Utopias, as we continue to grapple with the roles of housing, nature, and government in contemporary American life. Like the Greenbelt Towns themselves, the book is the result of communal effort. I’m fortunate to have Natasha Egan, executive director of the Museum of Contemporary Photography, who provided the artistic commentary and Dr. Robert Leighninger, author of Long-Range Public Investment: The Forgotten Legacy of the New Deal, who provided historical context. I’m also indebted to the Living New Deal for providing fiscal sponsorship for the project. Because of the Living New Deal, I was able to secure a publishing grant from the Puffin Foundation as well as connect with an extensive and supportive community committed to preserving the New Deal legacy.