“Curator Harvey Smith said on Thursday that he would like to show immigrants to the United States through a different [lens]. ‘This exhibition is about immigration, pluralism and internationalism, and I hope that the contributions of these immigrants can be recorded rather than forgotten in history.'” Read the World Journal‘s full coverage of the “Building Bridges, Not Walls” exhibition, curated by Living New Deal Project Advisor Harvey Smith, in its English translation (and in the original).

Frank da Cruz: Acknowledge Oval Park’s Milestone

“Norwood was once home to mainly those of Jewish, Irish, and Italian descent. Today it’s one of the city’s most diverse neighborhoods. All nationalities, races, ages, cultures, and religions come to Oval Park. To play, to socialize, to exercise, to relax; for romance, for picnics, and for special events. I believe that it’s one of the best utilized spaces in the whole city, every nook and cranny is used… except the bocce court! Everybody gets along, everybody watches out for everybody else.” New York-based Research Associate Frank da Cruz calls upon us to properly commemorate Oval Park, a WPA project in the Bronx that turns 80 this summer. Read more about the park’s history, the role it continues to hold in the community, and the importance of marking this site for posterity in his opinion piece for the Norwood News.

Thanks to Local Efforts, A New Deal Mural Is Saved

The newly-restored “Modern Education/School Activities”

© 2017 Pasadena Now. LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Since its completion in 1942, “Modern Education/School Activities” experienced the wear and tear and water damage that come with the decades. But who knew that this 16’ x 40’ oil-on-canvas mural, Painted by Frank Talles Chamberlain through the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), and hung in Pasadena’s McKinley School library, was so colorful and vibrant? Now, thanks to the McKinley School Mural Restoration Committee, and the painstaking work of conservators, we all do.

Its size and its place of prominence in view of young eyes speak to the importance of “Modern Education/School Activities” as a unique and vital artifact from the New Deal Era. Its conception and subject matter make it even more compelling for historians—and a still-relevant model for community. As Brandon Villalovos notes in Pasadena News Now, “After spending time in classrooms, it was Chamberlin’s idea that students would suggest ideas for the mural’s subject matter….. With a typical Southern California landscape as a backdrop, forty-nine students of different backgrounds participate in a number of activities such as chemistry, sculpture, radio transmission, horseback riding and blacksmithing. The mural conveys the artist’s passion and faith in the power of education.” Connecting the American pursuit of the arts and sciences to Classical ideals, it adds the New Deal twist of imagining this as a communitarian, multicultural endeavor, an under-appreciated pursuit of the era that we are currently chronicling in our “Working Together” page.

You can read about efforts to restore the mural—from fundraising to the work of conservators—and local reactions to its unveiling, in Villalovos’s article, “‘New Deal’ Era Mural at McKinley School, Carefully Restored After Civic Effort Raises $100,000, is Unveiled.”

Our New Map Featured in Untapped Cities

“From schools to murals and zoos, many of the projects created by the New Deal still exist today. According to Living New Deal, a team dedicated to keeping the legacy of the New Deal alive, New York received the most New Deal public works in the country and was the beneficiary of prominent projects such as the Triborough Bridge, LaGuardia Airport, and Riverside Park. And now, you can see some of the locations of these projects with Living New Deal’s New Deal New York map! They’ve mapped about one thousand locations (and there are still more being discovered).” In Untapped Cities’ “Mapping the New Deal in Each NYC Borough,” Stephanie Geier provides a detailed breakdown of our New Deal New York map.

Richard A Walker in the Brooklyn Rail

“Scanning the horizon of New York and beyond, New Deal sites number in the hundreds of thousands, most of them still in use today and almost none of them marked. There is the equivalent of a Lost Civilization out there waiting to be discovered. No one had ever documented everything the New Deal built or improved, until the Living New Deal was founded a decade ago to uncover the hundreds of thousands of public works across the country and map them, so that all Americans could see for themselves what was accomplished by their grandparents.” Read Richard A Walker’s entire Brooklyn Rail essay about how “The New Deal Lives On in the City” and our new pocket map honoring this legacy.

In The Guardian, Gray Brechin on Poverty Shaming

“The New Deal embodied an approach whose starting point was to make attacking poverty – not the people who live in it – a first principle. This makes it especially salient today… The writer and scholar Gray Brechin, a driving force behind the Living New Deal project, argues that at a time when Republicans in America and Tories in Britain behave as if there were no alternative to shrinking welfare states, and when ‘the dominant meme is that government just wastes money’, it is important that this ideology is exposed for the fiction that it is.” Read Mary O’Hara’s article, examining “lunch-shaming,” the “deeply flawed narrative that we can’t afford” the poor, and The Living New Deal’s attempt to commemorate a different vision of society.

Celebrate Our New Map with Us!

Vintage Postcard of the Triborough Bridge. © 2017, history.com

Two years in the making, The Living New Deal’s newest publication, a “Map and Guide to New Deal New York,” highlights nearly 1,000 public works throughout the five boroughs and describes 50 of the city’s notable New Deal buildings, parks, murals, and other sites and artworks. The 18 x 27 inch, multi-color map folds to pocket size, while three inset maps offer walking tours of the New Deal in Central Park, Midtown, and Downtown Manhattan.

In May, The Living New Deal will host events to celebrate our new map—and New Deal New York at large.

On Thursday, May 11, at the Roosevelt House at Hunter College, William Leuchtenburg, Marta Gutman, and Ira Katznelson will participate in the panel, “New Deal New York: A Living Legacy,” moderated by Owen Gutfreund. Following this, Living New Deal Director Richard A Walker will introduce our map. The panel begins at 6 pm, with a reception and map sales and signings to follow. RSVP here.

On Thursday, May 18, at the Museum of the City of New York, Mason Williams and Living New Deal founder Gray Brechin will participate in the panel, “Revisiting New York’s New Deal,” to be moderated by Sarah Seidman. The Museum will also open its gallery to visitors to see its exhibit, “Activist New York.” The panel begins at 6:30 pm, with a reception and map sales and signings to follow. RSVP here. Tickets are $10 with discount code “LND.”

Meanwhile, you can purchase the map ($6) and a poster version ($10) through our site.

Using WPA Art to Address Climate Change

Saguaro National Park, then and soon. © All Rights Reserved, 2017, Ranger Doug (rangerdoug.com) and Hannah Rothstein (hrothstein.com).

There are many ways to hold up the example of the New Deal in a time of greed, privatization, and creeping social and climatic threats. Celebrating public art and institutions, the USPS released 20 stamps reproducing works by the WPA’s Poster Division. In July, The Living New Deal will exhibit “Building Bridges, Not Walls,” commemorating the San Francisco Bay and Golden Gate bridges as the works of a diverse immigrant nation. (The Bay Bridge was a PWA project, while the Golden Gate Bridge received additions through the WPA.) But how can we both honor our New Deal heritage and adapt its problem-solving spirit for a new century? In National Parks 2050, Hannah Rothstein, a Berkeley-based visual artist, repurposes the New Deal’s visual grammar and rhetorical moves: appreciate our public spaces and rise to the challenge of saving them.

As someone who has been, she told us, long “inspired by the historical arts,” Rothstein, researching the effects of climate change on the parks and working from meticulous reproductions by Ranger Doug’s Enterprises, adapted posters created by the WPA/FAP between 1938 and 1941. Her versions serve a distinct purpose. The original posters advertised the glories of our national parks and monuments to inspire pride and tourism. But speaking to the unique challenges faced in each park amidst an administration unsympathetic to climate change and willing to cede public land to “energy development” (as compared with the parks’ massive expansion and conservation under the CCC), Rothstein replaces stirring and vibrant landscapes with denuded forests, dry lakes, and animal skulls. As she explains in her mission statement, National Parks 2050 draws on “the classic National Parks posters” to suggest “how climate change will affect seven of America’s most beloved landscapes. In doing so, it makes climate change feel close to home and hard to ignore.”

Consider her version of the poster for Saguaro National Monument (now Saguaro National Park, a beneficiary of CCC work). Where the original featured giant saguaros jutting towards a glowing sky of bright oranges, yellows, and blue, two men on horseback navigating a trail dotted with prickly pear and barrel cacti, Rothstein’s version muddies the sky to a pea soup green with dull red clouds, turns the saguaros into desiccated ruins, and swaps out the smaller vegetation for dry scrub. Where the original advertises “Guided Nature Trails & Winter Walks” of different trails and camps in the park, Rothstein’s version advertises “Dead saguaro, buffalograss invasion, species loss, drought,” suggesting what’s in store if we continue on our current path of disregarding ecologically devastating industrialization and consumption. Each of her posters addresses the specific threats facing different parks around the nation.

Rothstein explained that she couldn’t recall her own first encounters with specific New Deal artwork; but she remembers WPA structures from her childhood in Elmira, New York, part of a diffuse cultural landscape that should be familiar to us all. Indeed, she noted that the posters, and WPA art more generally, were “somewhere embedded in my cultural lexicon.” And therein lies her work’s power: Familiar-enough, cherished images that, upon further examination, force us to confront the prospect of a world where our “cultural lexicon” takes on bizarre shadings, producing a tragic new normal. National Parks 2050 is a vision of a fading collective purpose and landscape that we still might salvage if, as she hopes, we are willing to “start dialogue [on this] non-partisan issue.” You can support Rothstein—and the environment—by purchasing prints or originals, with 25% of the proceeds (40% on Earth Day) allocated to climate-related causes. See the project’s page for more information.

Gray Brechin contributed to this post.

A Window into New Deal Administration

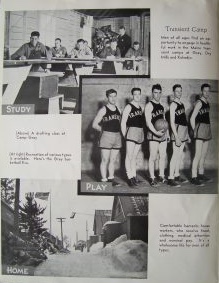

“Transient Camp” success stories. Courtesy of the Maine State Library.

Recently, Living New Deal Research Associate Andrew Laverdiere discovered a yearbook chronicling the work of the Maine Emergency Relief Administration (MERA) in 1934. Loaded with detailed breakdowns of how relief was administered, the structural organization of the Emergency Relief Administration, and expenditures and returns, Reviewing the ERA in Maine sheds light on the massive mobilization of the New Deal as it functioned in just one state.

More than simple accounting, Reviewing the ERA in Maine tells a human story. Participants in MERA not only built schools, they also taught in them. Mainers gave as much as they got. Indeed, we learn of the program that one of its key aims was to “derive for the public as much value as possible for the money expended.” It is a story of building and repairing communities and citizens alike. One of the more fascinating sections examines how “the Federal Government applied its funds for the care of transients” (pictured here). In exchange for classes, sports programs, and board and lodgings, more than 2000 young, formerly itinerant men constructed trout and salmon ponds and hatcheries. It was argued that “Many only needed the proper diet and simple life of the camps to enable them to once more take their place in the world.” You can find the entire source here.

Those “Dam Kids”: Lessons from the New Deal in Shasta County

Shasta Dam created thousands of jobs, facilitated the growth of surrounding towns, and reshaped California’s economy. © 2017, U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation.

Amidst Trump’s call to spend $1 trillion on infrastructure and the American Society of Civil Engineers’ recent Report Card for America’s Infrastructure (our GPA is a sad D+), Marketplace’s Sarah Gardner visited Shasta Lake, California, to get a sense of what large-scale projects once looked like for the people who built them, for their families, and for the folks who live in their shadows and benefit from them today. Indeed, Shasta Dam, a massive Bureau of Reclamation/Public Works Administration project, employed around 13,000-15,000 workers during the seven years (1938-1945) it took to build, fostered a boom town around it, and is today “a key part of California’s complex plumbing system” and central to its status as “an agricultural powerhouse.” We hear from New Deal scholars and from some of the “dam kids” (children of workers, as they were colloquially known) about the dam and life during the Great Depression and New Deal.

In terms of infrastructural benefits, employment opportunities, and the spirit of hard work and civic mindedness it fostered, Shasta Dam is a prime example of the positive legacies of the New Deal. But what would a massive public works program look like today, amidst changed circumstances? As economist Edward Glaeser notes in Gardner’s piece, “Much of infrastructure today is quite technologically intensive. It involves a lot of machines relative to the level of unskilled labor, and thinking that you’re just going to hop readily from one industry to another seems like a mistake.” Living New Deal Director Richard A Walker wades into the debate while further suggesting a crucial difference between then and now: “Why don’t we insulate every house and apartment in America? Think of the people we could put to work upgrading houses in every city, every town, every rural area to help with energy conservation. Those are not exotic, sophisticated projects.” Jason Scott Smith, a Living New Deal Research Board member and professor of History at the University of New Mexico, is also interviewed and notes that the New Deal sought to build “‘socially useful’ infrastructure.” In 2017, we need to also imagine what socially responsible infrastructure looks like.