- Home

- /

- Racism and Beyond: A...

- /

- A New Deal For...

- /

- American Indians and the...

American Indians and the New Deal

Scroll down for our photo gallery below!

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (IRA), sometimes called the “Indian New Deal”, was a turning point in the treatment of Native Americans by the federal government. In the 19th century, national policy was to seize a continent, by force as necessary, acquire land for American settlement and exploitation, and confine native peoples to reservations in limited areas of marginal value. The result was the devastation of native life, given the depredations of warfare, disease and displacement.

With the end of conquest, a new phase began with the Dawes Act of 1887, passed with the aim of converting the remaining Indians to American agrarian practices as small landholders and farmers. That, too, had disastrous effects. As one American Indian leader told Congress in 2011: “Kill the Indian and save the man was the slogan of that era… The Federal Government did everything it could to disband our tribes, break up our families and suppress our culture. Over 90 million acres of tribal land held under treaties were taken, more than two-thirds of the tribal land base… [Then] In 1934, Congress rejected allotment and assimilation and passed the IRA” [1].

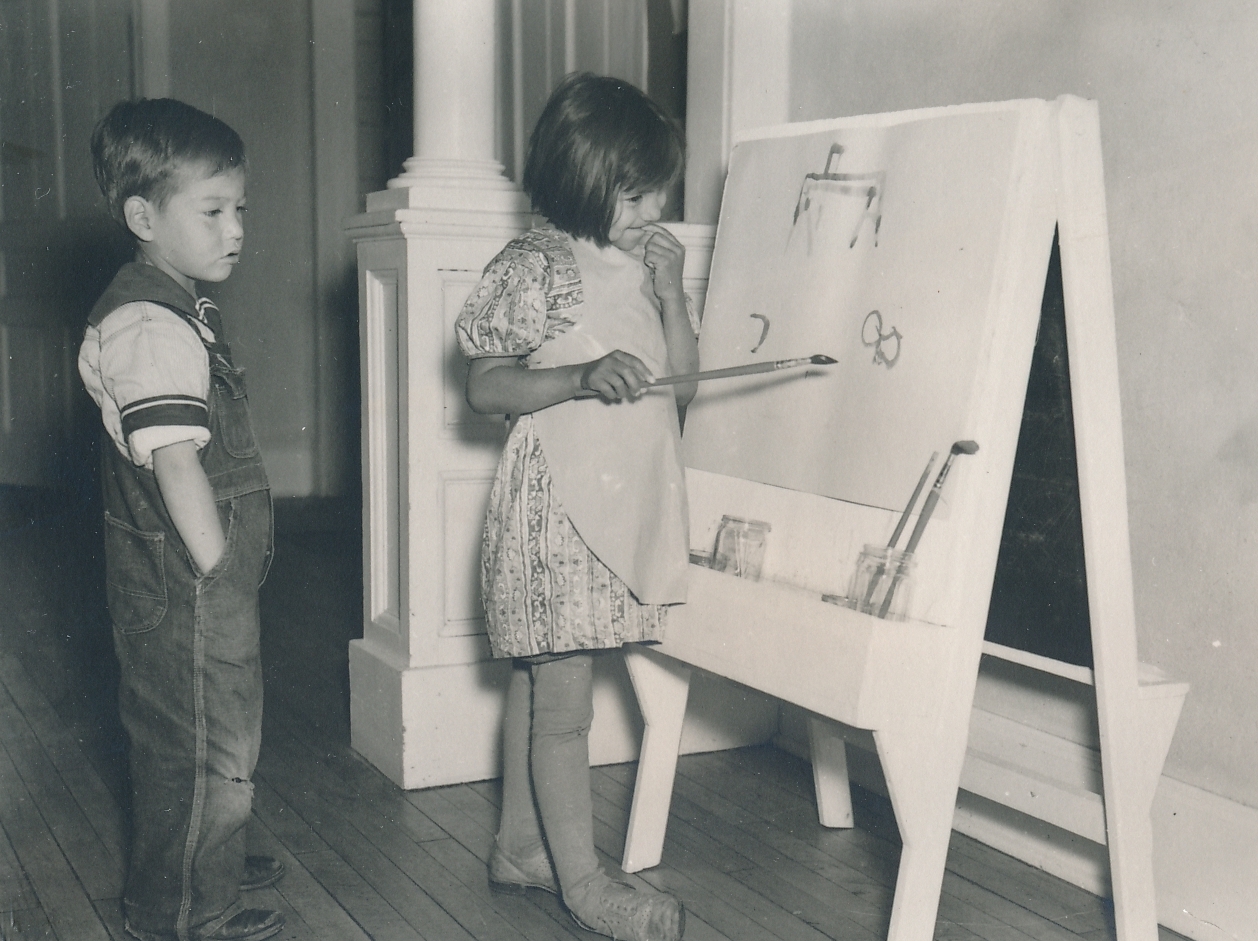

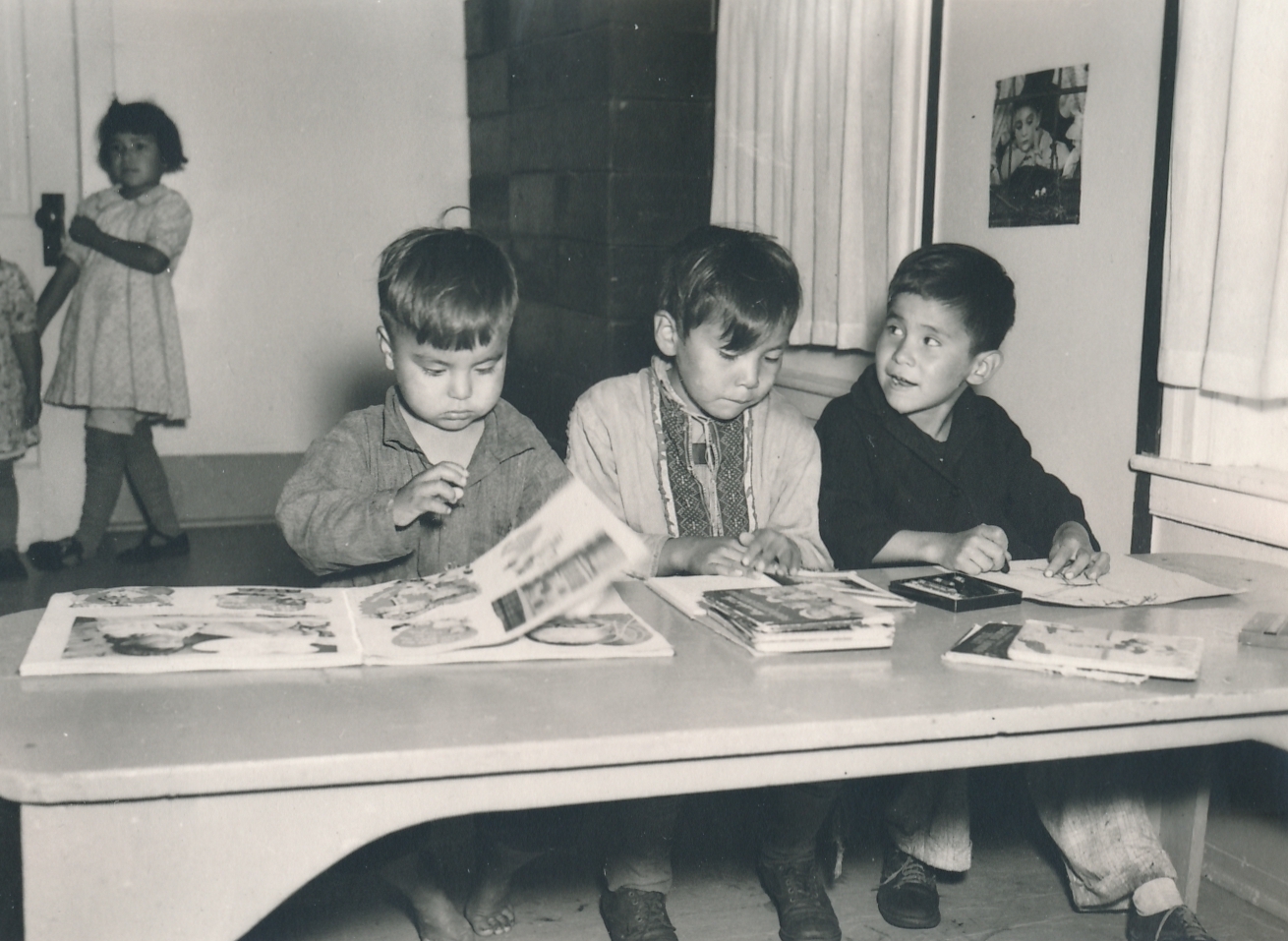

The IRA was the brainchild of Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier, an appointee of President Franklin Roosevelt. The law protected and restored land to American Indians, encouraged self-government, increased educational opportunities, and made available much-needed credit for small farms. The implementation of the law was not always perfect, but it marked a revolutionary change in the relationship between the federal government and the American Indian [2].

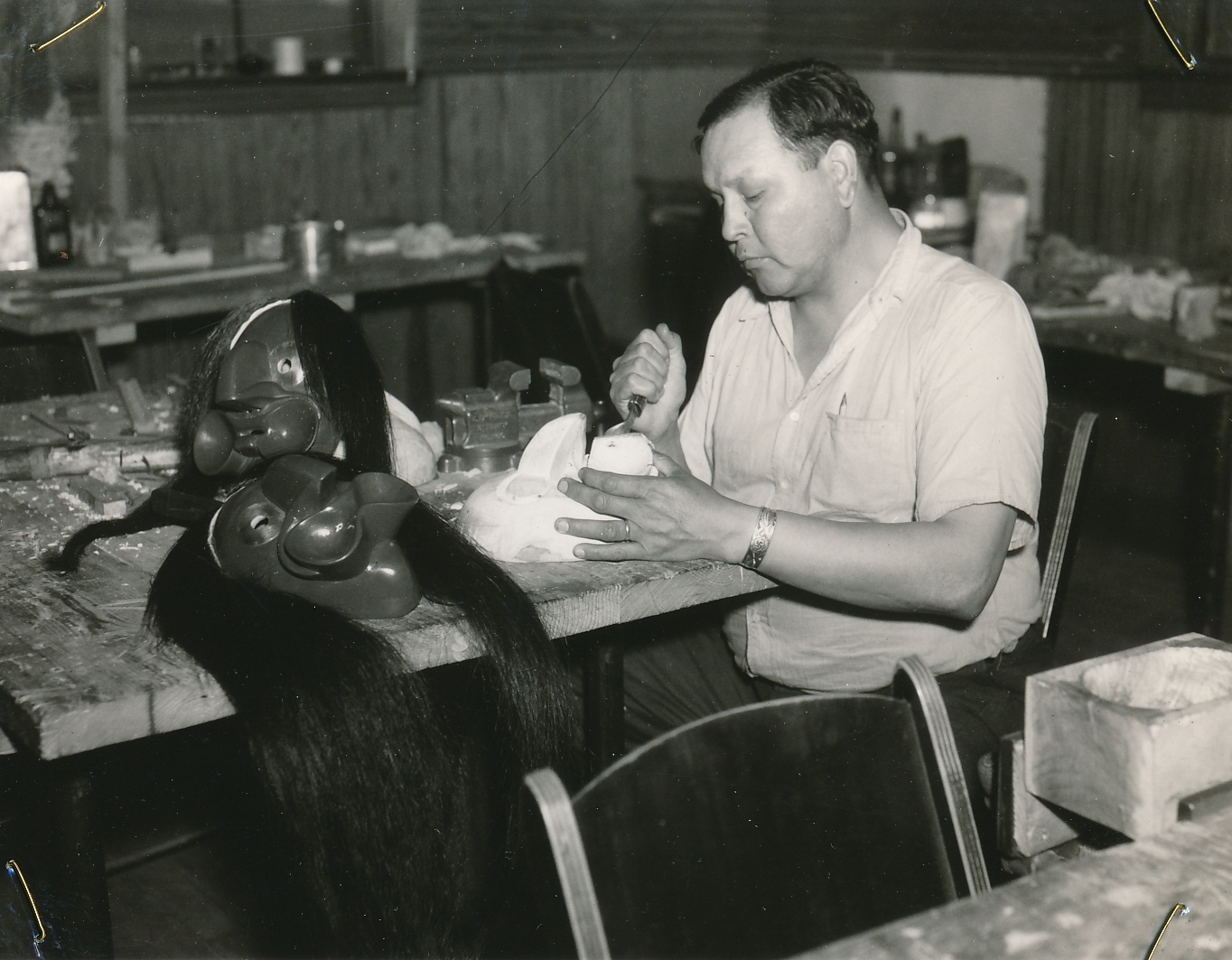

In the same New Deal spirit, Congress passed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act in 1935. The law recognized the importance American Indian art and put in place several mechanisms for its protection and promotion. Also, American Indians were employed on work-relief projects to create pottery, rugs, blankets, and other goods and handicrafts [3] and Indian artists were hired or commissioned by New Deal agencies to create art for public places across the country [4]. Today, the Indian Arts and Crafts Board (still part of the Department of the Interior) “promotes the economic development of American Indians and Alaska Natives of federally recognized Tribes through the expansion of the Indian arts and crafts market” [5].

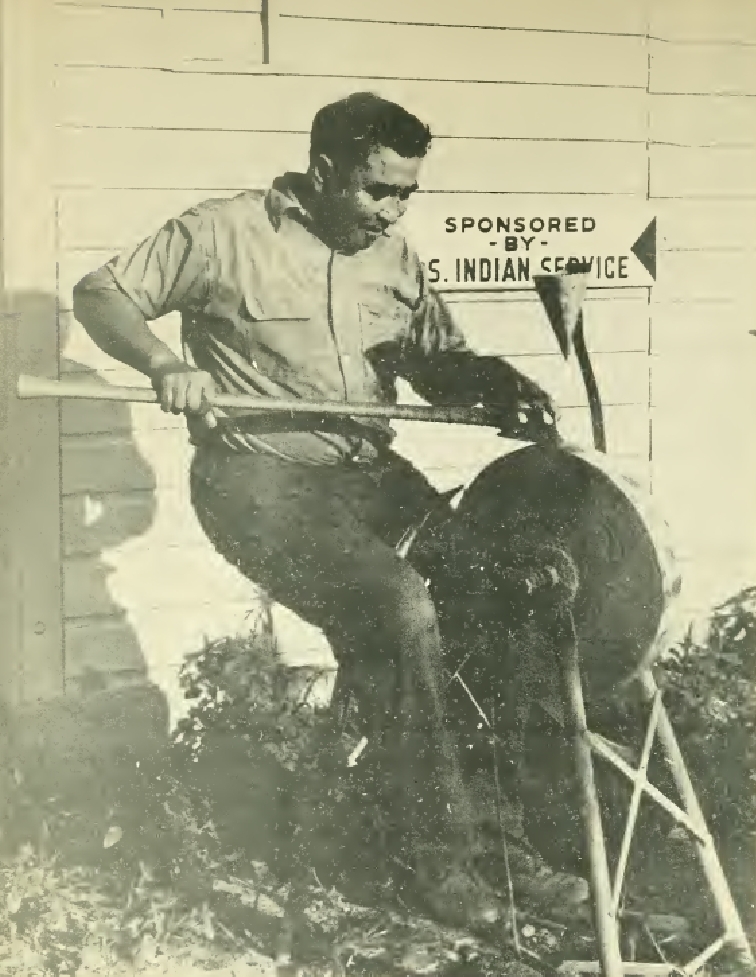

A key New Deal program that benefitted American Indians was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Between 1933 and 1942, over 85,000 American Indian men enrolled in the CCC, working on erosion control, forest management, roadwork, and so on. This work provided paychecks to people in need, improved reservation land, and lifted the spirits of many American Indians during the challenging times of the Great Depression [6]. One enrollee said: “This work has provided an income for us and has enabled us to keep alive while, at the same time, it has given us a better perspective on our goals in life” [7]. By the end of the CCC program, parts of 50 million acres on over 200 reservations in 23 states had been improved [8].

In addition, the New Deal developed the infrastructure on American Indian reservations, such as roads, schools and hospitals. These were funded by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Public Works Administration (PWA), and Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) [9].

As World War II arrived and the New Deal wound down, American Indians gave back to the country that had – finally – put its faith in them and provided them material support. For example, “Thousands of enrollees [in the CCC] became skilled workers as a direct result of their participation in the Corps and are now contributing to the war effort as members of the armed forces, as skilled workers in war industries, and as producers of food” [10]. Of particular note were the American Indian “code talkers” who “endured some of the most dangerous battles… served proudly, with honor and distinction…[and] are credited with saving thousands of American and allies’ lives” [11].

Sources: (1) “The Indian Reorganization Act—75 Years Later: Renewing Our Commitment to Restore Tribal Homelands and Promote Self–Determination,” Hearing Before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, One Hundred Twelfth Congress, First Session June 23, 2011, p. 67. (2) See our summary of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, and our biography of John Collier. (3) See, e.g., a Department of the Interior video showing American Indians on a WPA arts and crafts project: “The WPA on Indian Reservations” (YouTube, accessed April 11, 2018). (4) See, e.g., “Department of the Interior Building: Auchiah Murals – Washington, DC,” Living New Deal (accessed April 11, 2018). (5) “Indian Arts and Crafts Board,” Department of the Interior (accessed April 11, 2018). (6) Perry H. Merrill, Roosevelt’s Forest Army: A History of the Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-1942, Montpelier, VT, 1981, pp. 12, 31, 44-45. (7) “Unfortunate Indian – Fortunate,” Indians at Work, Office of Indian Affairs, Vol. 3, No. 22 (July 1, 1936), p. 19. (8) See note 6. (9) See, e.g., “The First Navajo PWA Day School Is Completed,” Indians at Work, Office of Indian Affairs, Vol. 2, No. 14 (March 1, 1935), p. 31. (10) See note 6, p. 45. (11) “Code Talking: Intelligence and Bravery,” National Museum of the American Indian (accessed April 11, 2018).