This conversation took place on March 21, 2015 at John’s home in Mill Valley, California.

John Roosevelt Boettiger

John is the grandson of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt

John, who was the person that most influenced you?

There isn’t any doubt that it was my grandmother, my mother’s mother Eleanor Roosevelt. We grandchildren called her Grandmère—she learned French before she learned English. She was such a gifted person. She let me absorb who she was and what she treasured. I think I learned my basic values from her. For example, her attachment to her family; her devotion to human rights; her absorption with the United Nations; her affection for Israel.

What are your early memories of her?

I was very young, but I still remember Grandmère getting off an airplane in Seattle and coming to stay with us on Mercer Island. Later, while I was still a young child, my mother and I moved to the White House during WWII, but I hardly remember her from that time because she was gone so much—overseas, visiting bases in the Pacific, London and elsewhere.

My memories of her are more vivid from the years I was a student at Amherst College. My parents had gone to Iran for two or three years so she said, as was her way, “Johnny, if you don’t have a home to go home to, you have mine. Come to New York City or Hyde Park, or wherever I am.” And I did.

What do you remember of those times?

On Grandmere’s lap

Anna Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt, John Boettiger, Jr., and Curtis Roosevelt. Source

There are so many memories…like when John Kennedy won the presidency from Richard Nixon and we watched it on television at her apartment on East 83rd Street; and when JFK visited her at her home in Hyde Park. There were two houses on her parcel of land on the estate at Hyde Park. The family home, Springwood, we called The Big House. Her home, Val-Kill, was named for the stream that meanders through the land. Her home at Val-kill was actually constructed as a small furniture factory that produced amazing reproductions of traditional American furniture. It was my grandmother’s way of employing a few local craftsmen who would not otherwise have had work.

I can tell you she was sometimes a perilous driver! Her son, Franklin, Jr. owned Fiat dealerships in the Southeast—one of his many enterprises—and gave her a little Fiat sports car. She would talk animatedly while driving. At the end of her driveway onto Route 9G, for example, she would stop, look both ways, and continue talking, sometimes for a minute or more. Then she would take off without looking again. But to my knowledge, she never ran into anyone.

Talk a bit about your grandmother’s involvement in the United Nations.

President Truman appointed her as a member of the American delegation to the United Nations. She was naturally drawn to the realm of human rights. More than any other single person, I think, she was responsible for the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The only standing ovation that the General Assembly has ever offered anyone was for her when she presented the Declaration, and it was unanimously approved.

Creation of the Declaration was very difficult process, given especially the U.S.’s relationship with the Soviet Union. But she managed to pilot it through to a unanimous conclusion. It was an astonishing act of creativity and political acumen.

My recollection is that in the late 1950s she was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. If only for that single accomplishment, she deserved it.

Did you travel with her during the time she was working for the UN?

I was too young to have been there when she was working on the Declaration, which was adopted in 1948. But I was in the Truman years and when Eisenhower and Kennedy were presidents. By then she was no longer an official member of the UN delegation, but a strong advocate. I traveled with her throughout the U.S. and in Europe.

I was too young to have been there when she was working on the Declaration, which was adopted in 1948. But I was in the Truman years and when Eisenhower and Kennedy were presidents. By then she was no longer an official member of the UN delegation, but a strong advocate. I traveled with her throughout the U.S. and in Europe.

She had amazing energy. I recall a trip in which my cousin, Haven Roosevelt, and I, as teenagers, were traveling with her. At around 5 o’clock we would stagger into our hotel room ready to hit the hay and she would say, “Now, children, remember we have a dinner with the mayor.” There was still a whole evening in front of us! I couldn’t believe the energy she brought to the whole of her life, almost to the very end. It was wonderful.

One of the secrets to her energy was her mastery of the power nap. When she and I both served as members of the Board of the American Association of United Nations, I as student representative, would sometimes sit across the table from her at meetings. She would nod her head slightly and close her eyes for a minute or two as if she were thinking carefully about what was going on. To the members at the table, she never missed a beat. I don’t think anyone but me knew she was napping.

You must have met some intriguing people.

One of the encounters I remember best was when I was in Berlin at a conference of the International Students Association of the U.N. My grandmother was elsewhere in Europe. I got a telephone call from her saying I must come to Brussels the next day, when she would be having lunch with Harry Belafonte. I had no idea even how to get to the airport, which was in East Berlin. But she said, “You must come!” It was a command performance.

I had a few German marks in my pocket and nearly was arrested by the East German police for inadvertently taking currency out the country, which was illegal. Luckily, a man behind me in line spoke German and defended my innocence. He saved me from jail.

We boarded an American DC-3, left over from the war and salvaged by the Poles. It was decorated it in a kind of Victorian style, with very plush seats and a tasseled interior. It was very foggy as we approached the airport in Brussels. The plane would descend, as if landing, and then suddenly and sharply rise again. This happened again and again. We were so low that I could I see telephone poles flashing by. The pilot had no radar and was looking for the runway! But I got there in time for lunch with Harry Belafonte, and I’m glad I did because I liked him a lot. My grandmother and I were together for the remainder of that trip.

Could she have imagined the role the UN would play today?

The role the UN is playing today is diverse, and less vigorous than she would have wished. My grandfather’s vision for the U.N.—and my grandmother’s nourishment of it—was that it would become principally an instrument for maintaining peace. But I think she had a sense that the U.N. was not going to be as central an organization as she and my grandfather had hoped. She would be disappointed, but I believe she would still be proud of it, and certainly working on its behalf if she were alive today.

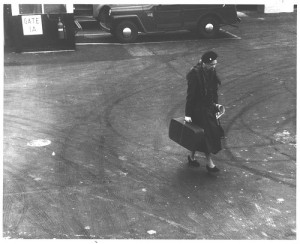

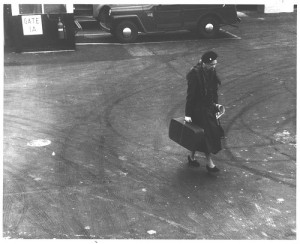

There’s a famous photograph of Mrs. Roosevelt walking toward a plane that’s parked on the tarmac, carrying her own suitcase.

There’s a famous photograph of Mrs. Roosevelt walking toward a plane that’s parked on the tarmac, carrying her own suitcase.

I never actually saw her walking with her suitcase, but she liked to travel quietly and without a big fuss. She didn’t like entourages. Of course, she would have them periodically, but she was very independent . It was her style.

How old were you when your grandmother died? Do you remember that time?

She died in the fall of 1962. I was 23. I remember visiting her at her New York apartment and in the hospital. She was so ill and immobilized that I think she didn’t want to continue. Life was no longer meaningful to her. I remember most vividly her funeral. It was a powerful and moving occasion. Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Mrs. Kennedy were there, as was Vice President Lyndon Johnson, and other heads of state. She is buried in the Rose Garden at Springwood with my grandfather. We thought of Springwood as a family home, but by then it had become a National Historic Site. It was strange to see velvet ropes placed in front of all the rooms we used to inhabit. With special permission, I able to go up the third floor where we, as kids during the war years, would be banished to the care of our nannies and nurses.

What do you remember of your grandfather?

FDR and grandchildren

Franklin D. Roosevelt III, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and John Roosevelt Boettiger, Christmas 1939 at The White House.

Photo Credit: From the Archives: First Families Celebrate the Holidays at the White House

We were living in Seattle when my father went off to war. My grandfather, whom I called PaPa, telephoned my mother and said, “Sis (his name for her), I wish you and Johnny would come here to live. I want you to be my right hand person.” None of his closest advisors—Louie Howe, Harry Hopkins—were there any longer. I remember the train trip across the country. I remember playing on the south lawn of the White House, the Easter egg hunts, even having a visit from the Lone Ranger and his horse Silver.

Silver was there too? You never told me that!

Silver was there! They brought him in a trailer. He got out and the Lone Ranger got on Silver and—I may be imagining this—I actually got to ride Silver!

It was in some ways a wonderful time, and also a very lonely one. I didn’t really have much of my mother. She was with her father, the president, almost the whole time. But he was very welcoming to me. I was the only child living in the White House during the war years, and I would be invited into his bedroom in the morning when he was reading his newspapers. The papers would be scattered over his bed. Despite the fact that he was paralyzed from his hips down, his upper body was extraordinarily strong. He would pluck me up from the floor and we’d sit together on the bed reading the funny papers.

I remember swimming with him in the White House pool, and playing in the Oval Office–not during important conferences, but when he was working at his desk. His desk was full of wind-up toys that I could reach up and take down to play with on the floor. And I remember my sense of kinship with the White House guards. But it wasn’t all fun. I felt also a sense of puzzlement and loneliness with my dad gone and my mother inaccessible much of the time.

Do you remember when your grandfather died?

The day my grandfather died—on April 12, 1945–I was in the hospital with a staph infection, which in those years could kill. My mother would come to visit, and my grandmother, too. I was getting well and looking forward to going home to The White House. I heard the announcement on the radio that the president had died. I knew my grandfather was president, but I couldn’t put him together with that announcement. A nurse came racing into the room and turned off the radio, thinking that I hadn’t yet heard the news. My mother soon made things clear. I was six years old. At that point my concern was what would happen to the toys I had left in my closet at The White House.

When you think about your famous family, and that they seem to belong to everyone, what comes up for you?

I hardly know what to think about it. I have such warm memories of them. It has seldom felt overwhelming to me to think of it as an extraordinary childhood. I did sometimes have the sense that there must have been expectations of me as a member of the Roosevelt family—expectations that I wouldn’t be up to. Only in that way was it a shadow inheritance. Now, in my 70s, in the community where I live, many people regard my grandfather as the president they knew better than any other. It’s been a satisfying experience to feel a sense of kinship with them.

Do you recall your grandmother advising you that you had a special role to play, or advice on how to live your life?

I don’t think she ever spoke in that way. She felt that if I was going to learn, better to learn by example. She surrounded me with her own magic.

John Roosevelt Boettiger is a retired professor of psychology and a member of the Living New Deal Advisory Board.

Susan Ives is communications director for the Living New Deal and editor of the Living New Deal newsletter.